clock This article was published more than 12 years ago

Book review: ‘Why Nations Fail,’ by Daron Acemoglu and James A. Robinson

“Why Nations Fail” is a sweeping attempt to explain the gut-wrenching poverty that leaves 1.29 billion people in the developing world struggling to live on less than $1.25 a day. You might expect it to be a bleak, numbing read. It’s not. It’s bracing, garrulous, wildly ambitious and ultimately hopeful. It may, in fact, be a bit of a masterpiece.

Daron Acemoglu and James A. Robinson, two energetic, widely respected development scholars, start with a bit of perspective: Even in today’s glum economic climate, the average American is seven times as prosperous as the average Mexican, 10 times as prosperous as the average Peruvian, about 20 times as prosperous as the average inhabitant of sub-Saharan Africa and about 40 times as prosperous as the average citizen of such particularly desperate African countries as Mali, Ethiopia and Sierra Leone. What explains such stupefying disparities?

The authors’ answer is simple: “institutions, institutions, institutions.” They are impatient with traditional social-science arguments for the persistence of poverty, which variously chalk it up to bad geographic luck, hobbling cultural patterns, or ignorant leaders and technocrats. Instead, “Why Nations Fail” focuses on the historical currents and critical junctures that mold modern polities: the processes of institutional drift that produce political and economic institutions that can be either inclusive — focused on power-sharing, productivity, education, technological advances and the well-being of the nation as a whole; or extractive — bent on grabbing wealth and resources away from one part of society to benefit another.

To understand what extractive institutions look like, consider les Grosses Legumes (the Big Vegetables), the sardonic Congolese nickname for the obscenely pampered clique around Mobutu Sese Seko, the strongman who ruled what is now the Democratic Republic of the Congo from 1965 to 1997. When Mobutu decreed that he wanted a palace built for himself at his birthplace, the authors note, he made sure that the airport had a landing strip big enough to accommodate the Concordes he liked to rent from Air France. Mobutu and the Big Vegetables weren’t interested in developing Congo. They were interested in strip-mining it, sucking out its vast mineral wealth for themselves. They were, at best, vampire capitalists.

But the roots of Congo’s nightmarish poverty and strife go back centuries. Before the arrival of European imperialists, what was then known as the Kingdom of Kongo was ruled by the oligarchic forerunners of the Big Vegetables, who drew their staggering wealth from arbitrary taxation and a busy slave trade. And when the European colonists showed up, they made a dreadful situation even worse — especially under the rapacious rule of King Leopold II of Belgium.

When Congo finally won its independence in 1960, it was a feeble, decentralized state burdened with a predatory political class and exploitative economic institutions — too weak to deliver basic services but just strong enough to keep Mobutu and his cronies on top; too poor to provide for its citizenry but just wealthy enough to give elites something to fight over.

Acemoglu and Robinson argue that when you combine rotten regimes, exploitative elites and self-serving institutions with frail, decentralized states, you have something close to a prescription for poverty, conflict and even outright failure. “Nations fail,” the authors write, “when they have extractive economic institutions, supported by extractive political institutions that impede and even block economic growth.”

But even as vicious cycles such as Congo’s can churn out poverty, virtuous cycles can help bend the long arc of history toward growth and prosperity. Contrast the conflict and misery in Congo with Botswana — which, when it won its independence in 1966, had just 22 university graduates, seven miles of paved roads and glowering white-supremacist regimes on most of its borders. But Botswana today has “the highest per capita income in sub-Saharan Africa” — around the level of such success stories as Hungary and Costa Rica.

How did Botswana pull it off? “By quickly developing inclusive economic and political institutions after independence,” the authors write. Botswana holds regular elections, has never had a civil war and enforces property rights. It benefited, the authors argue, from modest centralization of the state and a tradition of limiting the power of tribal chiefs that had survived colonial rule. When diamonds were discovered, a far-sighted law ensured that the newfound riches were shared for the national good, not elite gain. At the critical juncture of independence, wise Botswanan leaders such as its first president, Seretse Khama, and his Botswana Democratic Party chose democracy over dictatorship and the public interest over private greed.

In other words: It’s the politics, stupid. Khama’s Botswana succeeded at building institutions that could produce prosperity. Mobutu’s Congo and Robert Mugabe’s Zimbabwe didn’t even try. Acemoglu and Robinson argue that the protesters in Egypt’s Tahrir Square had it right: They were being held back by a feckless, corrupt state and a society that wouldn’t let them fully use their talents. Egypt was poor “precisely because it has been ruled by a narrow elite that has organized society for their own benefit at the expense of the vast mass of people.”

Such unhappy nations as North Korea, Sierra Leone, Haiti and Somalia have all left authority concentrated in a few grasping hands, which use whatever resources they can grab to tighten their hold on power. The formula is stark: Inclusive governments and institutions mean prosperity, growth and sustained development; extractive governments and institutions mean poverty, privation and stagnation — even over the centuries. The depressing cycle in which one oligarchy often replaces another has meant that “the lands where the Industrial Revolution originally did not spread remain relatively poor.” Nothing succeeds like success, Acemoglu and Robinson argue, and nothing fails like failure.

So what about China, which is increasingly cited as a new model of “authoritarian growth”? The authors are respectful but ultimately unimpressed. They readily admit that extractive regimes can produce temporary economic growth so long as they’re politically centralized — just consider the pre-Brezhnev Soviet Union, whose economic system once had its own Western admirers. But while “Chinese economic institutions are incomparably more inclusive today than three decades ago,”China is still fundamentally saddled with an extractive regime.

In fairly short order, such authoritarian economies start to wheeze: By throttling the incentives for technological progress, creativity and innovation, they choke off sustained, long-term growth and prosperity. (“You cannot force people to think and have good ideas by threatening to shoot them,” the authors note dryly.) Chinese growth, they argue, “is based on the adoption of existing technologies and rapid investment,” not the anxiety-inducing process of creative destruction that produces lasting innovation and growth. By importing foreign technologies and exporting low-end products, China is playing a spirited game of catch-up — but that’s not how races are won.

So how can the United States help the developing world? Certainly not by cutting foreign aid or conditioning it; as the authors note, you’d hardly expect someone like Mobutu to suddenly chuck out the exploitative institutions that underpin his power “just for a little more foreign aid,” and even a bit of relief for the truly desperate, even if inefficiently administered, is a lot better than nothing. But ultimately, instead of trying to cajole leaders opposed to their people’s interests, the authors suggest we’d be better off structuring foreign aid so that it seeks to bring in marginalized and excluded groups and leaders, and empowers broader sections of the population. For Acemoglu and Robinson, it is not enough to simply swap one set of oligarchs for another.

" Why Nations Fail " isn't perfect. The basic taxonomy of inclusive vs. extractive starts to get repetitive. After chapters of brio, the authors seem almost sheepish about the vagueness of their concluding policy advice. And their scope and enthusiasm engender both chuckles of admiration — one fairly representative chapter whizzes from Soviet five-year plans to the Neolithic Revolution and the ancient Mayan city states — and the occasional cluck of caution.

It would take several battalions of regional specialists to double-check their history and analysis, and while the overall picture is detailed and convincing, the authors would have to have a truly superhuman batting average to get every nuance right. Their treatment of the Middle East, for instance, is largely persuasive, but they are a little harsh on the Ottoman Empire, which they basically write off as “highly absolutist” without noting its striking diversity and relatively inclusive sociopolitical arrangements, which often gave minority communities considerably more running room (and space for entrepreneurship) than their European co-religionists.

Acemoglu and Robinson have run the risks of ambition, and cheerfully so. For a book about the dismal science and some dismal plights, “Why Nations Fail” is a surprisingly captivating read. This is, in every sense, a big book. Readers will hope that it makes a big difference.

is a senior political scientist at the RAND Corporation and a former adviser to U.S. ambassador to the United Nations Susan Rice.

WHY NATIONS FAIL

The Origins of Power, Prosperity, and Poverty

By Daron Acemoglu and James A. Robinson

Crown. 529 pp. $30

We are a participant in the Amazon Services LLC Associates Program, an affiliate advertising program designed to provide a means for us to earn fees by linking to Amazon.com and affiliated sites.

Paul Allen was one of the most intellectually curious people I’ve ever known.

Inclusive vs Extractive

Normally, I’m fairly positive about the books I review, but here’s one I really took issue with.

Why have some countries prospered and created great living conditions for their citizens, while others have not? This is a topic I care a lot about, so I was eager to pick up a book recently on exactly this topic.

Why Nations Fail is easy to read, with lots of interesting historical stories about different countries. It makes an argument that is appealingly simple: countries with “inclusive” (rather than “extractive”) political and economic institutions are the ones that succeed and survive over the long term.

Ultimately, though, the book is a major disappointment. I found the authors’ analysis vague and simplistic. Beyond their “inclusive vs. extractive” view of political and economic institutions, they largely dismiss all other factors—history and logic notwithstanding. Important terms aren’t really defined, and they never explain how a country can move to have more “inclusive” institutions.

For example, the book goes back in history to talk about economic growth during Roman times. The problem with this is that before 800AD, the economy everywhere was based on sustenance farming. So the fact that various Roman government structures were more or less inclusive did not affect growth.

The authors demonstrate an oddly simplistic world view when they attribute the decline of Venice to a reduction in the inclusiveness of its institutions. The fact is, Venice declined because competition came along. The change in the inclusiveness of its institutions was more a response to that than the source of the problem. Even if Venice had managed to preserve the inclusiveness of their institutions, it would not have made up for their loss of the spice trade. When a book tries to use one theory to explain everything, you get illogical examples like this.

Another surprise was the authors’ view of the decline of the Mayan civilization. They suggest that infighting—which showed a lack of inclusiveness—explains the decline. But that overlooks the primary reason: the weather and water availability reduced the productivity of their agricultural system, which undermined Mayan leaders’ claims to be able to bring good weather.

The authors believe that political “inclusiveness” must come first, before growth is achievable. Yet, most examples of economic growth in the last 50 years—the Asian miracles of Hong Kong, Korea, Taiwan, and Singapore—took place when their political tended more toward exclusiveness.

When faced with so many examples where this is not the case, they suggest that growth is not sustainable where “inclusiveness” does not exist. However, even under the best conditions, growth doesn’t sustain itself. I don’t think even these authors would suggest that the Great Depression, Japan’s current malaise, or the global financial crisis of the last few years came about because of a decline in inclusiveness.

The authors ridicule “modernization theory,” which observes that sometimes a strong leader can make the right choices to help a country grow, and then there is a good chance the country will evolve to have more “inclusive” politics. Korea and Taiwan are examples of where this has occurred.

The book also overlooks the incredible period of growth and innovation in China between 800 and 1400. During this 600-year period, China had the most dynamic economy in the world and drove a huge amount of innovation, such as advanced iron smelting and ship building. As several well-regarded authors have pointed out, this had nothing to do with how “inclusive” China was, and everything to do with geography, timing, and competition among empires.

The authors have a problem with Modern China because the transition from Mao Zedong to Deng Xiaoping didn’t involve a change to make political institutions more inclusive. Yet, China, by most measures, has been a miracle of sustained economic growth. I think almost everyone agrees that China needs to change its politics to be more inclusive. But there are hundreds of millions of Chinese whose lifestyle has been radically improved in recent years, who would probably disagree that their growth was “extractive.” I am far more optimistic than the authors that continued gradual change, without instability, will continue to move China in the right direction.

The incredible economic transition in China over the last three-plus decades occurred because the leadership embraced capitalistic economics, including private property, markets, and investing in infrastructure and education.

This points to the most obvious theory about growth, which is that it is strongly correlated with embracing capitalistic economics—independent of the political system. When a country focuses on getting infrastructure built and education improved, and it uses market pricing to determine how resources should be allocated, then it moves towards growth. This test has a lot more clarity than the one proposed by the authors, and seems to me fits the facts of what has happened over time far better.

The authors end with a huge attack on foreign aid, saying that most of the time, less than 10% gets to the intended recipients. They cite Afghanistan as an example, which is misleading since Afghanistan is a war zone and aid was ramped up very quickly with war-related goals. There is little doubt this is the least effective foreign aid, but it is hardly a fair example.

As an endnote, I should mention that the book refers to me in a positive light, comparing how I made money to how Carlos Slim made his fortune in Mexico. Although I appreciate the nice thoughts, I think the book is quite unfair to Slim. Almost certainly, the competition laws in Mexico need strengthening, but I am sure that Mexico is much better off with Slim’s contribution in running businesses well than it would be without him.

I found an unintentional theme connecting them all.

Brave New Words paints an inspiring picture of AI in the classroom.

Infectious Generosity is a timely, inspiring read about philanthropy in the digital age.

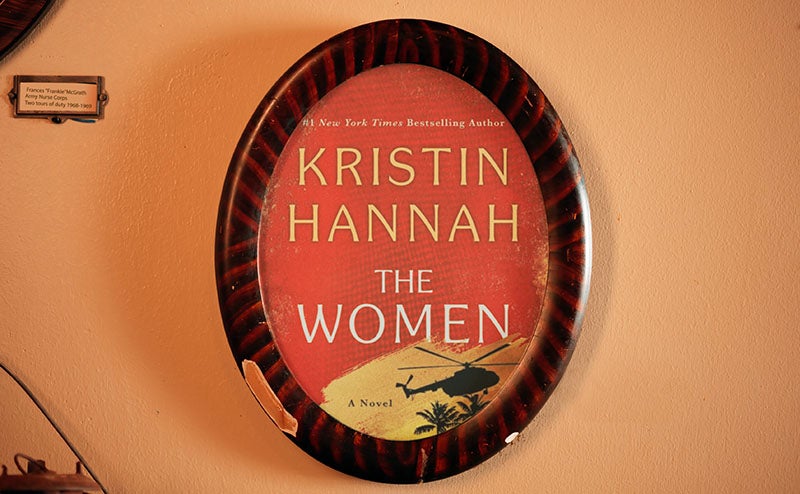

The Women gave me a new perspective on the Vietnam War

Kristin Hannah’s wildly popular novel about an army nurse is eye-opening and inspiring.

This is my personal blog, where I share about the people I meet, the books I'm reading, and what I'm learning. I hope that you'll join the conversation.

Q. How do I create a Gates Notes account?

A. there are three ways you can create a gates notes account:.

- Sign up with Facebook. We’ll never post to your Facebook account without your permission.

- Sign up with Twitter. We’ll never post to your Twitter account without your permission.

- Sign up with your email. Enter your email address during sign up. We’ll email you a link for verification.

Q. Will you ever post to my Facebook or Twitter accounts without my permission?

A. no, never., q. how do i sign up to receive email communications from my gates notes account, a. in account settings, click the toggle switch next to “send me updates from bill gates.”, q. how will you use the interests i select in account settings, a. we will use them to choose the suggested reads that appear on your profile page..

- NONFICTION BOOKS

- BEST NONFICTION 2023

- BEST NONFICTION 2024

- Historical Biographies

- The Best Memoirs and Autobiographies

- Philosophical Biographies

- World War 2

- World History

- American History

- British History

- Chinese History

- Russian History

- Ancient History (up to c. 500 AD)

- Medieval History

- Military History

- Art History

- Travel Books

- Ancient Philosophy

- Contemporary Philosophy

- Ethics & Moral Philosophy

- Great Philosophers

- Social & Political Philosophy

- Classical Studies

- New Science Books

- Maths & Statistics

- Popular Science

- Physics Books

- Climate Change Books

- How to Write

- English Grammar & Usage

- Books for Learning Languages

- Linguistics

- Political Ideologies

- Foreign Policy & International Relations

- American Politics

- British Politics

- Religious History Books

- Mental Health

- Neuroscience

- Child Psychology

- Film & Cinema

- Opera & Classical Music

- Behavioural Economics

- Development Economics

- Economic History

- Financial Crisis

- World Economies

- Investing Books

- Artificial Intelligence/AI Books

- Data Science Books

- Sex & Sexuality

- Death & Dying

- Food & Cooking

- Sports, Games & Hobbies

- FICTION BOOKS

- BEST NOVELS 2024

- BEST FICTION 2023

- New Literary Fiction

- World Literature

- Literary Criticism

- Literary Figures

- Classic English Literature

- American Literature

- Comics & Graphic Novels

- Fairy Tales & Mythology

- Historical Fiction

- Crime Novels

- Science Fiction

- Short Stories

- South Africa

- United States

- Arctic & Antarctica

- Afghanistan

- Myanmar (Formerly Burma)

- Netherlands

- Kids Recommend Books for Kids

- High School Teachers Recommendations

- Prizewinning Kids' Books

- Popular Series Books for Kids

- BEST BOOKS FOR KIDS (ALL AGES)

- Books for Toddlers and Babies

- Books for Preschoolers

- Books for Kids Age 6-8

- Books for Kids Age 9-12

- Books for Teens and Young Adults

- THE BEST SCIENCE BOOKS FOR KIDS

- BEST KIDS' BOOKS OF 2024

- BEST BOOKS FOR TEENS OF 2024

- Best Audiobooks for Kids

- Environment

- Best Books for Teens of 2024

- Best Kids' Books of 2024

- Mystery & Crime

- Travel Writing

- New History Books

- New Historical Fiction

- New Biography

- New Memoirs

- New World Literature

- New Economics Books

- New Climate Books

- New Math Books

- New Philosophy Books

- New Psychology Books

- New Physics Books

- THE BEST AUDIOBOOKS

- Actors Read Great Books

- Books Narrated by Their Authors

- Best Audiobook Thrillers

- Best History Audiobooks

- Nobel Literature Prize

- Booker Prize (fiction)

- Baillie Gifford Prize (nonfiction)

- Financial Times (nonfiction)

- Wolfson Prize (history)

- Royal Society (science)

- NBCC Awards (biography & memoir)

- Pushkin House Prize (Russia)

- Walter Scott Prize (historical fiction)

- Arthur C Clarke Prize (sci fi)

- The Hugos (sci fi & fantasy)

- Audie Awards (audiobooks)

- Wilbur Smith Prize (adventure)

Nonfiction Books » Economics Books

Why nations fail, by daron acemoglu & james robinson, recommendations from our site.

“The key to this book is really all in an early example in the text, where they cite the small town of Nogales on the Arizona-Mexico border. The border basically goes through the middle of the town: you can drive a cigarette paper through the differences between the people on the two sides of the border. They’re from similar families, they’re related, they have shared history and so on, but one of them is in North America, and the other is in Mexico. There are visible and quite stark contrasts in the standards of living and prosperity of people who live either side of the border. The question they ask is, how did this happen? This leads them to an issue which crops up in Ian Morris’s book as well, and I think is an absolutely essential factor to look at when we try to understand relative speeds and levels of economic development, which is the role of inclusive institutions.” Read more...

The best books on Emerging Markets

George Magnus , Economist

“ Why Nations Fail is by two of my favourite economists, two very close friends and co-authors of mine, Daron Acemoglu and James Robinson. They’re tackling a subject that I’ve worked on with them, and they do a great job of bringing it to life and making it vivid. Why Nations Fail is one of those books that stretches your mind and gives you all these examples and connections between them, so that you come away from it saying, “Wow. I didn’t know that.” It’s really, really interesting.” Read more...

The best books on Why Economic History Matters

Simon Johnson , Economist

“In terms of understanding this top inequality, I mentioned the possibility that it might be about politics. How should we think about politics? What are the levers of politics? For that we need a conceptual framework and that’s what this book tries to provide. It’s co-authored with my long-term collaborator and friend Jim Robinson – and it’s not about US or UK or Canadian inequality. It runs through several thousand years of history, and tries to explain how societies work and why, often, they fail to generate prosperity for their citizens. It’s a very political story.” Read more...

The best books on Inequality

Daron Acemoglu , Economist

Other books by Daron Acemoglu and James Robinson

The narrow corridor: states, societies, and the fate of liberty by daron acemoglu & james robinson, power and progress: our thousand-year struggle over technology and prosperity by daron acemoglu & simon johnson, introduction to modern economic growth by daron acemoglu, economic origins of dictatorship and democracy by daron acemoglu & james robinson, our most recommended books, the big short: inside the doomsday machine by michael lewis, a monetary history of the united states, 1867-1960 by anna schwartz & milton friedman, the wealth and poverty of nations by david s landes, this time is different by carmen reinhart & kenneth rogoff, the worldly philosophers by robert l heilbroner, the passions and the interests by albert hirschman.

Support Five Books

Five Books interviews are expensive to produce, please support us by donating a small amount .

We ask experts to recommend the five best books in their subject and explain their selection in an interview.

This site has an archive of more than one thousand seven hundred interviews, or eight thousand book recommendations. We publish at least two new interviews per week.

Five Books participates in the Amazon Associate program and earns money from qualifying purchases.

© Five Books 2024

The Journal for Student Geographers

A review of ‘Why Nations Fail’

By Fintan Hogan, King Edward VI Camp Hill School for Boys

Acemoglu, Daron., and James A. Robinson. Why Nations Fail : The Origins of Power, Prosperity, and Poverty. London: Profile, 2012.

Hogan, F. (2020) A review of ‘Why Nations Fail’. Routes 1(2): 251–255.

This piece reviews the 2012 book Why Nations Fail , co-authored by Daron Acemoglu and James A. Robinson (Acemoglu & Robinson, 2012). Their work focuses on the role of institutions in fostering development; specifically economic institutions like secure property rights and political institutions like free and fair elections – structures that commonly develop hand-in-hand. However, throughout the book, the authors write as we would expect geographers to do; frequently contextualising their argument with broader quantitative and qualitative data. Despite an apparent focus on the economic and the political, the social aspects of geography validate their argument throughout.

1. Introduction

Political accountability means the powerful can no longer rob the weak. That’s the basic premise of Why Nations Fail , with a consistent focus on the political and economic rights afforded to people over the last few millennia. The book may more accurately be called ‘Why Nations Succeed’ , since the authors draw policy prescriptions from some of the most advanced economies of each era. Reviewing a book which explicitly rejects geography as an explanation for development may appear counter-intuitive for Routes , but on reflection, the premise put forward by Acemoglu and Robinson is crucial to any understanding of development dynamics seen through a geographical lens. Daron Acemoglu is a Professor of Economics at MIT and James Robinson teaches Economics at the University of Chicago – it makes sense then, that they would see economic institutions as uniquely pivotal throughout. While Chapter 2, entitled ‘Theories That Don’t Work’, rejects ‘The Geography Hypothesis’ (p48), one should not be so quick to believe that the discipline has little to learn from their conclusions. On the contrary, geographers are concerned with the flow of information, expansion of trade and progression of inequality, all of which play pivotal roles in the authors’ premise.

Daron Acemoglu and James A Robinson offer a concise summary of their premise in the very final line of the book: ‘…durable political reform, will depend, as we have seen in many different instances, on the history of economic and political institutions, on many small differences that matter and on the very contingent path of history’ (p462). To use their own terminology, the argument held throughout the book is that development is only sustained through ‘inclusive economic and political institutions’, supported through a ‘virtuous’ positive feedback cycle – illustrated through charting the Neolithic, Industrial and Technological Revolutions. Through this, they reject ‘extractive political and economic institutions’ which facilitate growth for a short amount of time (catch-up) and profit very few people, stalling ‘creative destruction’ and generating ‘vicious’ cycles. As such, low taxes and strong central government are seen as important characteristics of a nation’s success. An example of how this may develop in practice could be citizen assemblies or unions providing some political accountability – through this, the economic security of workers grows, and development follows. In advancing their argument, the authors use a wealth of historical sources in what becomes a compelling and universal argument.

2. A more nuanced view of geography

In fact, what the authors reject in Chapter 2 is physical geography ; the site and situation which people find themselves in. This theory has been termed environmental, or geographical, determinism and has been repopularised by academics like Jared Diamond of Guns, Germs and Steel fame (Diamond, 1999). Prisoners of Geography is another popular text in this vein, emphasising the importance of the physical environment on modern-day geopolitics (Marshall, 2015). These readings are sometimes termed ‘man-land geography’ too, emphasising the interaction between the natural environment and those who rely on it. To a certain extent, Acemoglu & Robinson are correct in their reasoning that broadly similar climates and reliefs can yield vastly different results, and they use colonial and post-colonial Congo to illustrate localised disparities (p58).

Despite this, they appear to neglect the fact that modern technology still overwhelmingly benefits from a positive location. Geographers from as early as GCSE learn of hydropower and its benefits to Ethiopia, alongside containerisation and how it fails to help landlocked Malawi or mountainous Nepal. Despite this, their argument broadly holds true – on the whole, regions with similar soils, coasts and rainfall can have hugely divergent development pathways. They argue that small changes in institutions are widened into cavernous gaps following ‘critical junctures’ – for example, the decentralised workforce of England led to the Peasants Revolt following the Black Death; this improved working conditions, unlike in much of Eastern Europe (p96). Now you may ask, doesn’t this sound a lot like history? Indeed it does, and this is what continually struck me while reading. The use of the phrase ‘contingent path of history’ to wrap up the entire book shows this clearly and demonstrates how their argument rests on singular people and events, rather than trends or patterns, as indeed does the term ‘critical junctures’.

3. Geography underpins the argument

Well what does Geography offer to this reading? Unquestionably a huge amount. The concept Acemoglu and Robinson revere in particular is participation – using the example of the Glorious Revolution (1688), the authors argue that a broad coalition of interests acts as an effective set of checks and balances within the group, supporting the introduction of equality and representation. What geography shows here is how these groups of people emerge, regardless of individual figures, in a collection of diverse interests. Understanding wealth and its distribution is shared with Economics, but underpinning a geographical perspective is the idea of social capital, inclusivity and community – the authors themselves seem to recognise this with the divergence in the distribution of serfdom across Europe by 1800 (p108). While all European peasants in the early Middle Ages were subjugated to feudalism, by the 19 th century the western European poor had strong social cohesion, fuelled by urbanisation, while those in eastern Europe still remained scattered, facing coerced farm labour. Demography and culture are as important as any purely economic factor – geography highlights the importance of place to this institutional drift.

One needs to look no further than the A Level Changing Places topic to understand how, as geographers, we can understand a community, looking beyond their economic or political standing, in a way which ‘the contingent path of history’ often relies on. It is easy to argue that historical events drive development, because every occurrence can be seen as a direct cause. However, the authors’ historical accounts are frequently contextualised by pieces of relevant data, demonstrating the importance of a wider societal understanding which underpins everything that the book has to offer. Understanding development through a geographical perspective offers the sort of coherent wider picture which the authors rely on throughout.

4. Conclusion

In short, geography is crucial to understanding the conditions which allow for the emergence of institutional reform, rather than attributing change just to single political figures or fateful events. In the modern world, this exposes itself through free trade and the exchange of services, individuals and ideas. The very first example in the book used Nogales, USA and Nogales, Mexico (a city divided by a fence) to highlight extreme inequality (p7). In the 21 st century, we attribute this to policy attitudes towards loans, welfare, property rights and globalisation. While the authors here employ the catch-all term of ‘institutions’, what the readers of this journal will be able to ascertain is far deeper. As geography students and researchers, we can perceive far more from history than what just individuals or economics can tell us. Without this wider view, historians would fail to really understand the preconditions for development (Rostow, 1959), using circular logic to suggest that developed economies must have experienced ‘good development’ and underdeveloped ones ‘bad’. Incorporating the authors’ ideas into academic studies is likely to give students another insight into development factors, and their global exploration contextualises some key areas of GCSE and A Level content. Geography moves beyond a narrow idea of development, complimenting and supporting the entire premise of the text. I would encourage you to perhaps pick up a copy of this 500-page tome – it’s worth a read.

5. References

Acemoglu, D & Robinson, J.A. (2012) Why Nations Fail: The Origins of Power, Prosperity and Poverty , New York: Crown

Diamon, J (1999) Guns, germs and steel: The fates of human societies , New York: WW. Norton & Co.

Marshall, T (2015) Prisoners of Geography: Ten Maps That Tell You Everything You Need to Know About Global Politics , London: Elliott & Thompson

Rostow, W (1959) The Stages of Economic Growth , The Economic History Review, New Series, Vol 12, No. 1, pp1-16

#Write for Routes

Are you 6th form or undergraduate geographer?

Do you have work that you are proud of and want to share?

Submit your work to our expert team of peer reviewers who will help you take it to the next level.

Related articles

Share this:

- Already have a WordPress.com account? Log in now.

- Subscribe Subscribed

- Copy shortlink

- Report this content

- View post in Reader

- Manage subscriptions

- Collapse this bar

- Skip to main content

- Keyboard shortcuts for audio player

Planet Money

- Planet Money Podcast

- The Indicator Podcast

- Planet Money Newsletter Archive

- Planet Money Summer School

- LISTEN & FOLLOW

- Apple Podcasts

- Amazon Music

Your support helps make our show possible and unlocks access to our sponsor-free feed.

A Nobel prize for an explanation of why nations fail

Greg Rosalsky

Academy of Sciences permanent secretary Hans Ellegren (C), Jakob Svensson (L) and Jan Teorell of the Nobel Assembly sit in front of a screen displaying the laureates (L-R) Turkish-American Daron Acemoglu and British-Americans Simon Johnson and James Robinson of the 2024 Sveriges Riksbank Prize in Economic Sciences in Memory of Alfred Nobel during the announcement by the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences in Stockholm, Sweden on October 14, 2024. (Photo by Christine Olsson/TT / TT NEWS AGENCY / AFP) / Sweden OUT (Photo by CHRISTINE OLSSON/TT/TT NEWS AGENCY/AFP via Getty Images) CHRISTINE OLSSON/TT/TT NEWS AGENCY/AFP via Getty Ima/AFP hide caption

On January 6th, 2021, rioters stormed the United States Capitol building. To many of us, it felt like one of the bedrock institutional traditions of our democracy was in jeopardy: the peaceful transition of power to a leader elected by the people.

As inauguration day approached, Americans feared that more violence was possible. Thousands of National Guard troops descended on the capital to keep the peace. And our democratic institutions felt more fragile than ever.

Being an econ nerd, my mind immediately went to the work of MIT economist Daron Acemoglu and University of Chicago economist and political scientist James Robinson. The two, who co-authored the book Why Nations Fail , had done really important research explaining why institutions are so critical to a nation’s success or failure. I wanted to get their perspective during a critical moment in American history, when our democratic institutions seemed to be weaker than they used to be. So I called them up.

Well, yesterday, the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences, which awards some of the Nobel prizes, also called them up. It awarded the Nobel Memorial Prize in Economic Sciences to Acemoglu and Robinson — as well as their collaborator, MIT economist Simon Johnson — for their research on “how institutions are formed and affect prosperity.”

It’d be one thing for Acemoglu, Robinson, and Johnson to simply argue that institutions are critical to determining how rich a nation becomes. But, being economists, they also did some incredible statistical work to try and prove it.

For example, in one famous paper cited by the prize committee, Acemoglu, Robinson, and Johnson found there was a “reversal of fortune” in the wake of European colonization of the Americas. South and Central America went from being relatively richer than North America before colonization to being relatively poorer afterwards.

Why did this reversal happen? Acemoglu, Robinson, and Johnson argued that it’s all because of differences in the institutions created by European colonizers. In the Northern United States and Canada, Europeans created “inclusive” institutions that protected individual freedom and property rights, enforced the rule of law, educated their populations, and encouraged innovation and entrepreneurialism — institutions that would serve the economy especially well with the coming industrial revolution. The reason why Europeans set up inclusive institutions here, the prize winners explained, was because North America had a smaller, less dense indigenous population, so the Europeans could settle in large numbers and set about governing themselves.

In South and Central America, where there were the Incan and Aztec empires, there were too many indigenous people for Europeans to simply move in and govern themselves. Instead, European colonizers introduced or maintained already-existing “extractive” institutions that were geared more towards exploiting and oppressing the indigenous population. These institutions were not aimed at, for example, protecting individual freedom, investing in and educating the population, or encouraging innovation. Instead, these nations got a set of institutions that would be ill-suited for them to succeed in a modern, innovative industrial economy.

Acemoglu, Robinson, and Johnson argue that these institutional differences persisted over time, explaining why there was a reversal in fortune — that is, why North America became so much richer than South and Central America. The paper finds a similar story in other countries that Europeans colonized around the world.

The Deion Sanders Of Economics

When I got news of the award, I got to say, I was really excited, especially for Daron Acemoglu. I’ve been poring over his research for many years. In fact, one of the joys of my job at Planet Money has been getting to speak with him on multiple occasions and being able to pick his brain.

Yesterday, George Mason University economist Alex Tabarrok called Acemoglu “the Wilt Chamberlain of economics” because he's “an absolute monster of productivity who racks up the papers and the citations at nearly unprecedented rates.”

Maybe it’s because Chamberlain was before my time, but, to me, Acemoglu is more like the Deion Sanders of economics. When he played football, Sanders was a superstar who could score touchdowns on offense, defense, and special teams. Sanders was also a star baseball player. More recently, Sanders became a football coach and has killed it doing that.

Likewise, Acemoglu has been a superstar in multiple academic disciplines and subfields. He’s made massive contributions not just to institutional economics, development economics, and political science (the area in which he just won a Nobel for), but also in realms like mathematical economics, economic growth, political economy, and the economics of technology and automation.

Acemoglu has been a fixture in the Planet Money Newsletter. In fact, Acemoglu made an appearance in last week’s newsletter ! Acemoglu’s work was also featured in a recent newsletter on why artificial intelligence may be overrated ; another on why artificial intelligence isn’t wiping out jobs even in areas where it seems to be really good ; and another explaining Acemoglu's profound insights about automation .

And, of course, Acemoglu — and his co-author and co-Nobel-prize-winner James Robinson — appeared in a newsletter explaining their (now) Nobel prize-winning research into the role that institutions play in a nation’s economic success.

Given the Nobel news, we figured it’d be worth revisiting this newsletter from January 2021, which explored their ideas about the power of institutions and how they thought those ideas related to the United States during a volatile period in our history. Here it is (you can also read it here ):

Democracy Under Siege

As we approach inauguration day, exactly two weeks after the Capitol insurrection, Americans are on edge. About twenty thousand National Guard soldiers will provide security tomorrow; more troops than in Iraq and Afghanistan. Our political situation feels shaky and our institutions fragile. It's like we’re living in a bad Tom Clancy novel. We couldn’t reach Tom Clancy, so we called up the authors of Why Nations Fail instead. We wanted to figure out if the insurrection is a sign our nation is failing, and, if so, if there’s anything we can do about it.

“I don’t think January 6th was a singular day of failure,” says MIT economist Daron Acemoglu, who co-authored the book with University of Chicago economist James Robinson. “What surprises me is why it took until January 6th.”

WASHINGTON, DC - JANUARY 14: Members of the New York National Guard stand guard along the fence that surrounds the U.S. Capitol the day after the House of Representatives voted to impeach President Donald Trump for the second time January 14, 2021 in Washington, DC. Thousands of National Guard troops have been activated to protect the nation's capital against threats surrounding President-elect Joe Biden’s inauguration and to prevent a repeat of last week’s deadly insurrection at the U.S. Capitol. (Photo by Chip Somodevilla/Getty Images) Chip Somodevilla/Getty Images/Getty Images North America hide caption

Drawing on decades of economic research, Why Nations Fail argues that political institutions — not culture, natural resources or geography — explain why some nations have gotten rich while others remain poor. A good example is North Korea and South Korea. Eighty years ago, the two were virtually indistinguishable. But after a civil war, North Korea turned to communism, while South Korea embraced markets and, eventually, democracy. The authors argue that South Korea's institutions are the clear reason that it has grown insanely more rich than North Korea.

Nations like South Korea have what Acemoglu and Robinson call "inclusive institutions," such as representative legislatures, good public schools, open markets and strong patent systems. Inclusive institutions educate their populations. They invest in infrastructure. They fight poverty and disease. They encourage innovation. They are far different from the "extractive institutions" found in countries like North Korea, Venezuela and Saudi Arabia, where small groups of elites use state power for their own ends and prosper through corruption, rent-seeking or brutally forcing people to work.

When Acemoglu and Robinson wrote Why Nations Fail almost a decade ago, they used the United States as an institutional success story. They acknowledge the nation has a dark side: slavery, genocide of Native Americans, the Civil War. But it's also a creature of the Enlightenment, a place with free and fair elections and world-renowned universities; a haven for immigrants, new ideas and new business models; and a country responsive to social movements for greater equality. Lucky for America — and its economy — its inclusive institutions have had a helluva run.

So, almost 10 years later, how do Acemoglu and Robinson feel about American institutions?

"U.S. institutions are really coming apart at the seams — and we have an amazingly difficult task of rebuilding them ahead of us," Acemoglu says. "This is a perilous time."

Acemoglu and Robinson see the rising tide against liberal democracy in America as a reaction to our political failure to deal with festering economic problems. In their view, our institutions have become less inclusive, and our economic growth now benefits a smaller fraction of the population. Some of the best economic research over the last couple of decades confirms this. Wage growth for most has stagnated . Social mobility has plummeted . Our labor market has been splitting into two , where the college educated thrive and those without a degree watch their opportunities shrivel, after automation and trade with China destroyed millions of jobs that once gave them good wages and dignity.

Acemoglu and Robinson believe that while factors like the transformation of our media landscape play a role, these economic changes and our political institutions' failure to grapple with them are the primary cause of our growing cultural and political divides. "As opposed to some of the left, who think this is all just the influence of big money or deluded masses, I think there is a set of true grievances that are justified," Acemoglu says. "Working-class people in the United States have been left out, both economically and culturally."

"Trump understood these grievances in a way the traditional parties did not," Robinson says. "But I don't think he has a solution to any of them. We saw something similar with the populist experiences in Latin America, where having solutions was not necessary for populist political success. Did Hugo Chávez or Juan Perón have a solution to these problems? No, but they exploited the problems brilliantly for political ends."

For Acemoglu and Robinson, more democracy is the answer to our political and economic problems. In a gigantic study of 175 countries from 1960 to 2010, they found that countries that democratized saw a 20% increase in GDP per capita over the long run.

Asked how we can stop our slide into national dysfunction, Acemoglu argues that political leaders need to focus on those who've been left behind and give them a leg up and a stake in the system. He advocates for a "good jobs" agenda that envisions policy changes and public investments to create, naturally, good jobs and shared prosperity ( read more here ). Robinson, citing the work of Harvard University political scientist Robert Putnam, argues we should find ways to transcend our political and cultural differences and connect with fellow citizens beyond our political tribes.

"We are still at a point where we can reverse things," Acemoglu says. "But I think if we paper over these issues, we will most likely see a huge deterioration in institutions. And it can happen very rapidly."

Let's hope they don't have to revise their book.

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

The Acemoglu/Robinson thesis, as presented in their book "Why Nations Fail," posits that the key determinant of a nation's success is its political and economic institutions. They argue that inclusive institutions lead to …

Why Nations Fail is easy to read, with lots of interesting historical stories about different countries. It makes an argument that is appealingly simple: countries with “inclusive” (rather than “extractive”) political and economic …

To forgo reading Why Nations Fail – a weighty but intensely engaging investigation of the determinants of economic prosperity – is, it seems, to risk being left out of …

Why Nations Fail. by Daron Acemoglu & James Robinson. Recommendations from our site. “The key to this book is really all in an early example in the text, where they cite the small town of Nogales on the Arizona-Mexico border.

Abstract. This piece reviews the 2012 book Why Nations Fail, co-authored by Daron Acemoglu and James A. Robinson (Acemoglu & Robinson, 2012). Their work focuses on the role of institutions in fostering development; …

Drawing on decades of economic research, Why Nations Fail argues that political institutions — not culture, natural resources or geography — explain why some nations have …