What does it mean to be human?

By Jon Farrar

What does it mean to be human? It’s a simple question, just a few short words, but it unwraps the bundle of complexity, contradictions, and mystery that is a human life.

It’s a question we have been asking for thousands of years. Priests and poets, philosophers and politicians, scientists and artists have all sought to answer this ultimate puzzle, but all fell short, never able to fully capture the vastness of the human experience.

More on Science

Some have come closer than others.

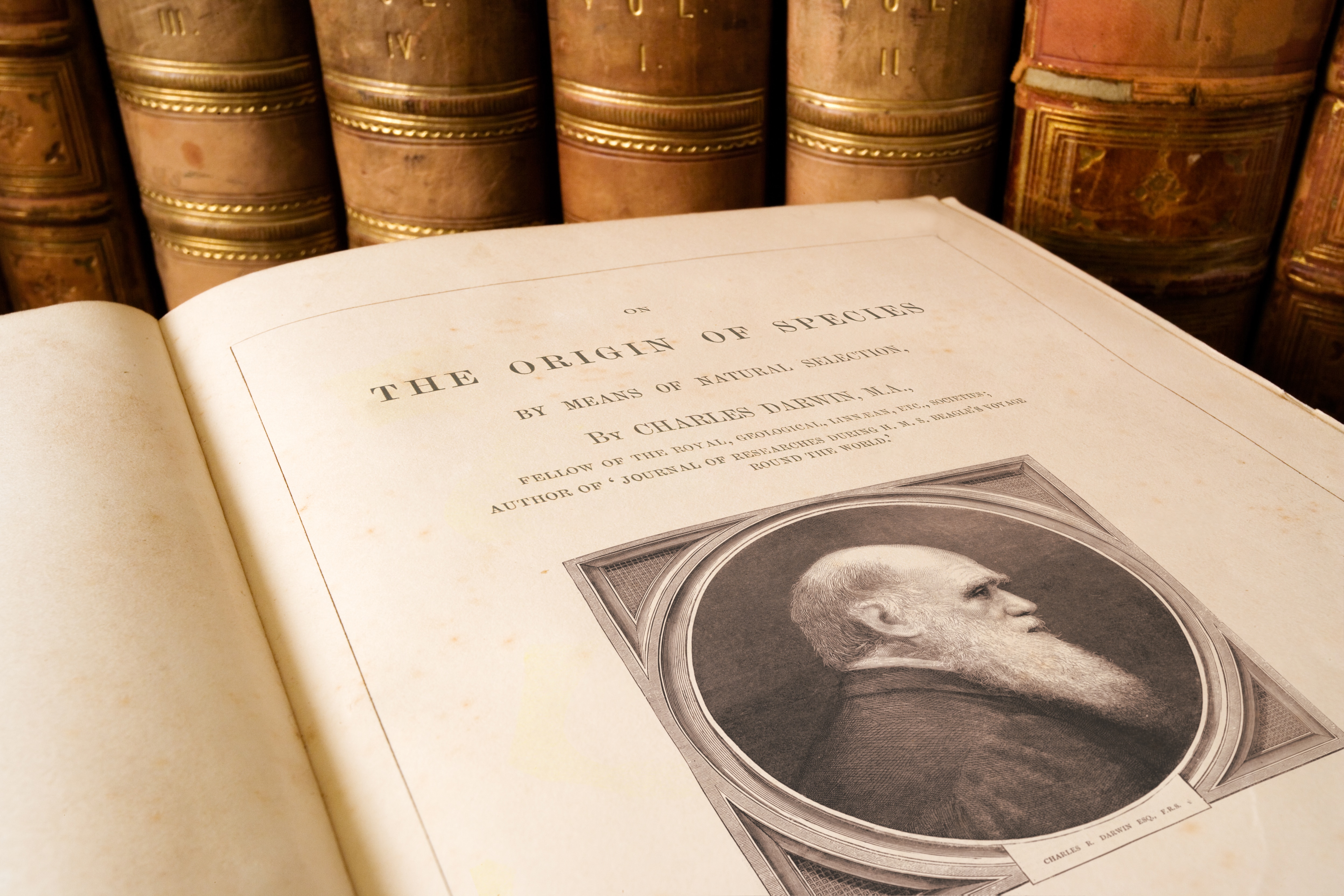

Charles Darwin had one of the greatest insights into the human condition that any of our species has had, changing thousands of years' of thought at the stroke of a pen, yet he had nothing to say about how we actually experience being human.

It would be another 50 years before an Austrian doctor began to talk about the hidden forces of the subconscious mind, but even Sigmund Freud couldn’t provide an adequate explanation for consciousness. In fact, to date, no-one has come close to describing the sheer magnificent wonder of being alive. The electric surge we feel when we kiss a lover, the deep stirring of the soul when we listen to Mozart’s Requiem, and the full flowing joy of laughing uncontrollably with our closest friends as we share a joke.

Being Human is a major new season launching on BBC Earth that aims to take us as closer to understanding who we are. Why do we behave the way we do? How do we live better? How did we get to now? What is our future?

Over the course of a year, we will take you by the hand and dive into these questions, exploring all corners of humanity with wide-eyed curiosity. We will look deep into the mind at what drives our behaviour, meet extraordinary humans who have unlocked the secrets of a long and healthy life, take a trip through 2000 years of civilisation, journey into the human body on our path to adulthood as we go from baby to baby-maker, experience the drama of extraordinary human rituals that hope to cheat death, and watch happens to our bodies in the hours, days, and months after we die.

We have brilliant series from world class programme makers coming up, full of incredible ideas at the leading edge of scientific thought. We want to make you think, but we also want to make you feel. Being Human will be a celebration of the human race. We want to make the hairs on the back of the neck stand up at the improbable good fortune of our own existence.

So what is our story? Let’s start with the facts. We are one species of primate that emerged from the dry savannahs of East Africa just over 100,000 years ago and began a migration that continues to today.

We weren’t the strongest animal, but we had an unusually large brain and held ourselves upright, giving us a high vantage to scan the distant horizon for enemies, and the freedom to use our hands for other purposes. Over time we began to fashion tools. These were primitive, but could tear through skin and muscle and gave us an advantage as we prowled our wild habitat for prey.

We might have continued our short life of hunting, savagery, and brutishness right through to today, but for one important development - language. Other animals could communicate, but we evolved astonishing vocal ability, able to create sounds that represented not just objects, but also concepts. We learned how to express ideas. We could speak of danger, hope, and love. We became storytellers, able to weave together common narratives about who we are and how we should live. From this point on the pace of change was electrifying.

Twelve thousand years ago, we learned how to domesticate plants and other animals for food, and were able to settle in one place. We became a social animal, building complex communities that become kingdoms, learning to trade with each other using a concept called money.

By 2500 years ago, a small group of humans in Southern Europe and the Middle East started to ask big questions about who we were. What is the best way to live? What is a good life? What does it mean to be human? How we responded to these questions is how we built our civilisation, art, and philosophy. Five hundred years ago, the scientific revolution began, allowing us to harness the resources of our planet to live longer and more productive lives.

When the digital revolution began only 50 years ago, the world shrank. We became a global village, our hopes and dreams converted into an infinite stream of ones and zeroes echoing throughout cyberspace. Today, we stand astride the world as a god, with both the power to destroy our own planet and to create life.

We may even be the last of our species to be fully human as bio-technology and artificial intelligence begin to rip apart the very core of who we are. Indeed, our Being Human campaign is led by Sophia, an incredible lifelike robot who is developing her own intelligence. She looks human, she sounds human, but she cannot yet think or feel like a human. How many years until she is truly one of us? Or we are one of them?

Our story is remarkable. The greatest story ever told. And while it is the story of astonishing development for our species, it is also the tale of billions of individual lives echoing down the millennia, all of them full of hope and promise, fear and disappointment. As we discover more about reality, we continue our ascent into insignificance, becoming a vanishing footnote in space and time, a speck of dust in the vastness of the universe. But to be human is to be at the centre of our own universe, to experience life in all its colours and all its potential. This is what we want to celebrate with Being Human - the awe of being alive and the thrill of discovering what it means to be us, the greatest wonder in the world.

Inspiration

BBC Earth delivered direct to your inbox

Sign up to receive news, updates and exclusives from BBC Earth and related content from BBC Studios by email.

What Does It Mean to Be Human?

We can’t turn to science for an answer..

Posted May 16, 2012 | Reviewed by Matt Huston

What does it mean to be human? Or, putting the point a bit more precisely, what are we saying about others when we describe them as human? Answering this question is not as straightforward as it might appear. Minimally, to be human is to be one of us, but this begs the question of the class of creatures to which “us” refers.

Can’t we turn to science for an answer? Not really. Some paleoanthropologists identify the category of the human with the species Homo sapiens , others equate it with the whole genus Homo , some restrict it to the subspecies Homo sapiens sapiens , and a few take it to encompass the entire hominin lineage. These differences of opinion are not due to a scarcity of evidence. They are due to the absence of any conception of what sort of evidence can settle the question of which group or groups of primates should be counted as human. Biologists aren’t equipped to tell us whether an organism is a human organism because “human” is a folk category rather a scientific one.

Some folk-categories correspond more or less precisely to scientific categories. To use a well-worn example, the folk category “water” is coextensive with the scientific category “H2O.” But not every folk category is even approximately reducible to a scientific one. Consider the category “weed.” Weeds don’t have any biological properties that distinguish them from non-weeds. In fact, one could know everything there is to know biologically about a plant, but still not know that it is a weed. So, at least in this respect, being human is more like being a weed than it is like being water.

If this sounds strange to you, it is probably because you are already committed to one or another conception of the human (for example, that all and only members of Homo sapiens are human). However, claims like “an animal is human only if it is a member of the species Homo sapiens ” are stipulated rather than discovered. In deciding that all and only Homo sapiens are humans, one is expressing a preference about where the boundary separating humans from non-humans should be drawn, rather than discovering where such a boundary lays.

If science can’t give us an account of the human, why not turn to the folk for an answer?

Unfortunately, this strategy multiplies the problem rather than resolving it. When we look at how ordinary people have used the term “human” and its equivalents across cultures and throughout the span of history, we discover that often (maybe even typically) members of our species are explicitly excluded from the category of the human. It’s well-known that the Nazis considered Jews to be non-human creatures ( Untermenschen ), and somewhat less well-known that fifteenth-century Spanish colonists took a similar stance towards the indigenous inhabitants of the Caribbean islands, as did North Americans toward enslaved Africans (my 2011 book Less Than Human: Why We Demean, Enslave, and Exterminate Others , gives many more examples). Another example is provided by the seemingly interminable debate about the moral permissibility of abortion, which almost always turns on the question of whether the embryo is a human being.

At this point, it looks like the concept of the human is hopelessly confused. But looked at in the right way, it’s possible to discern a deeper order in the seeming chaos. The picture only seems chaotic if one assumes that “human” is supposed to designate a certain taxonomic category across the board (‘in every possible world’ as philosophers like to say). But if we think of it as an indexical expression – a term that gets its content from the context in which it is uttered – a very different picture emerges.

Paradigmatic indexical terms include words like “now,” “here,” and “I.” Most words name exactly the same thing, irrespective of when, where, and by whom they are uttered. For instance, when anyone anywhere correctly uses the expression ‘the Eiffel Tower,’ they are naming one and the same architectural structure. In contrast, the word “now” names the moment at which the word is uttered, the word “here” names the place where it is uttered, and the word “I” names the person uttering it. If I am right, the word “human” works in much the same way that these words do. When we describe others as human, we are saying that they are members of our own kind or, more precisely, members of our own natural kind.

What’s a natural kind? The best way to wrap one’s mind around the notion of natural kinds is to contrast them with artificial kinds. Airplane pilots are an artificial kind, as are Red Sox fans and residents of New Jersey, because they only exist in virtue of human linguistic and social practices, whereas natural kinds (for example, chemical elements and compounds, microphysical particles, and, more controversially, biological species) exist ‘out there’ in the world. Our concepts of natural are concepts that purport to correspond to the structural fault-lines of a mind-independent world. In Plato’s vivid metaphor, they ‘cut nature at its joints.’ Weeds are an artificial kind, because they exist only in virtue of certain linguistic conventions and social practices, but pteridophyta (ferns) are a natural kind because, unlike weeds, their existence is insensitive to our linguistic conventions.

Philosophers distinguish the linguistic meaning of indexical expressions from their content. The content of an indexical is whatever it names. For example, if you were to say ‘I am here’, the word ‘here’ names the spot where you are sitting. Its linguistic meaning is ‘the place where I am when I utter the word “here”.’ If ‘human’ means ‘my own natural kind,’ then referring to a being as human boils down to the assertion that the other is a member of the natural kind that the speaker believes herself to be. This goes a long way towards explaining why a statement of the form ‘x is human,’ in the mouth of a biologist might mean ‘x is a member of the species Homo sapiens ’ while the very same statement in the mouth of a Nazi might mean ‘x is a member of the Aryan race.’ That's what it means to be human.

David Livingstone Smith, Ph.D ., is professor of philosophy at the University of New England.

- Find Counselling

- Find Online Therapy

- South Africa

- Johannesburg

- Port Elizabeth

- Bloemfontein

- Vereeniging

- East London

- Pietermaritzburg

- Asperger's

- Bipolar Disorder

- Chronic Pain

- Eating Disorders

- Passive Aggression

- Personality

- Goal Setting

- Positive Psychology

- Stopping Smoking

- Low Sexual Desire

- Relationships

- Child Development

- Self Tests NEW

- Therapy Center

- Diagnosis Dictionary

- Types of Therapy

When we fall prey to perfectionism, we think we’re honorably aspiring to be our very best, but often we’re really just setting ourselves up for failure, as perfection is impossible and its pursuit inevitably backfires.

- Emotional Intelligence

- Gaslighting

- Affective Forecasting

- Neuroscience

Please contact the OCIO Help Desk for additional support.

Your issue id is: 4759646968869670116.

Shelley’s Frankenstein: What It Means to Be Human Essay

Frankenstein, a ground-breaking novel by Mary Shelley published in 1818, raises important questions about what it means to be human. Mary Shelley was inspired to write the book in response to the questions arising from growing interactions between indigenous groups and European colonialists and explorers. While the native people the Europeans encountered exhibited human characteristics, the Europeans generally viewed them as inferior and less intelligent. Therefore, at that time, there was an unending debate about whether non-European ethnicities belonged to the same species as Europeans. The contestation was largely influenced by the Enlightenment led by the philosopher David Hume, who argued that there were different species of people and non-European species were “naturally inferior to the whites” (Lee 265). As a result, the native people were positioned beneath the line dividing humans from animals. This essentially meant they would only be subjects of slavery and oppression. However, Shelly’s Frankenstein runs counter to this theory and challenges the rigid notion of being a human based on a synthetic creature made of dead bodies. The book reveals what it means to be human through the creature’s actions.

When Frankenstein was released, many people were mesmerized by stories of “wild” native tribes in distant lands. Lee (267) states that during that time, the native people were judged only based on their appearance and way of life. However, going by Shelly’s progressive and broader definition, anyone would qualify to be called a human being in their own right. Shelly’s illustration even included the “savages” that her contemporaries looked down upon. Shelly uses the classic example of a creature that could survive on a vegetarian diet and climb mountains relatively easily. Her depiction of the creature through Victor Frankenstein shows that he is innately tied to the natural world (Shelley 85). However, the horrific responses he receives from others, including his creator, causes him to live in exile away from the European culture and dwell in the woods.

Furthermore, the creature’s looks make it obvious that it is not European. It stands at “nearly eight feet tall,” is far taller than the average European, and has “yellow skin” and “straight black lips” (Shelley 59). Even though a European developed him, his physical distinctiveness “the work of muscles and arteries beneath” set him apart from others (Shelley 59). Because he has been cast out of society due to his appearance, the creature is not a party to the social contract of the Enlightenment, a tacit agreement between all members of a country to protect each other’s basic rights. When the creature meets others, they fail in their duty to protect his human rights as a group, and later in the book, he murders in retaliation. The pervasive Enlightenment conception of the social contract generates an abstract divide between “civilized man” and “natural man” (Lee 275). The contract allows man to transition out of his “state of nature” and into modern society. That is why most Europeans, the moment Frankenstein was published, would not have understood how deeply connected to nature the creature or many indigenous peoples were.

Notwithstanding the deep connection to nature, the creature is human and characterized by an emotional and often compassionate personality. Despite his young age, he is almost as emotional and just as eloquent as his creator. When Felix, a young farmer whose home he stays in for a while, attacks him, he refrains from retaliation and saves a young girl only from being shot by her male companion. He frequently exhibits more moral “human” behavior than those he meets (Shelley 130). In both instances, he exhibits kindness and mercy and is unjustly assaulted by humans who misjudge him. At one time, the creature gets confronted, causing an aggressive, malicious, and vengeful reaction. However, the creature exemplifies intense guilt at the novel’s conclusion, which characterizes humanity. The creature’s depiction as physically non-European, self-educated, and yet unquestionably human can be applied to the indigenous people in nations like South America that European explorers frequently encountered. The indigenous people were characterized by their lifestyle and appearance rather than their inherent intelligence or upbringing. They can only exist in the natural world because they are not mostly allowed to live in European culture.

In conclusion, Shelley used her book, Frankenstein, to show what it means to be human through the creature’s actions. She broadens the definition of humanity by creating a progressive vision that enables those deemed less human to be regarded as completely human. The creature’s actions, when confronted, act as a caution against the risks of treating other people with indignity. Shelley’s story urges the reader to allow everyone to prove themselves before judging them based on their appearance. She advocates for fair treatment by drawing comparisons between the creature and its existence in nature and indigenous peoples worldwide, both forms of the “other.” As shown by the creature’s actions, anyone could end up becoming what is unfairly expected of them if they are not given an equal chance because of the psychological harm caused by the way they have been treated. In the end, the discovery that both the indigenous and the creature are human but are not perceived as such in civilization exposes the flaws in the prejudiced yet obscured view of humanity held by the Enlightenment.

Works Cited

Lee, Seogkwang. “ Humanity in Monstrous Form: Reading Mary Shelley Frankenstein .” The Journal of East-West Comparative Literature , vol. 49, 2019, pp. 261–85, Web.

Shelley, Mary. Frankenstein, or, the Modern Prometheus . Legend Press, 2018.

- "A Modest Proposal" by Jonathan Swift: Life on the Island

- The Novel “The Ocean at the End of the Lane” by Neil Gaiman

- “Frankenstein” by Mary Shelley

- Ethics of Discovery in Mary Shelley's "Frankenstein"

- Frankenstein's Historical Context: Review of "In Frankenstein’s Shadow" by Chris Baldrick

- King Lear as a Depiction of Shakespeare's Era

- Themes in "Dancing in the Dark" Novel by Phillip

- The "Dancing in the Dark" Novel by Caryl Phillip

- "Frankenstein" by Mary Shelley Review

- Lewis' The Lion, the Witch, and the Wardrobe Book

- Chicago (A-D)

- Chicago (N-B)

IvyPanda. (2023, December 17). Shelley's Frankenstein: What It Means to Be Human. https://ivypanda.com/essays/shelleys-frankenstein-what-it-means-to-be-human/

"Shelley's Frankenstein: What It Means to Be Human." IvyPanda , 17 Dec. 2023, ivypanda.com/essays/shelleys-frankenstein-what-it-means-to-be-human/.

IvyPanda . (2023) 'Shelley's Frankenstein: What It Means to Be Human'. 17 December.

IvyPanda . 2023. "Shelley's Frankenstein: What It Means to Be Human." December 17, 2023. https://ivypanda.com/essays/shelleys-frankenstein-what-it-means-to-be-human/.

1. IvyPanda . "Shelley's Frankenstein: What It Means to Be Human." December 17, 2023. https://ivypanda.com/essays/shelleys-frankenstein-what-it-means-to-be-human/.

Bibliography

IvyPanda . "Shelley's Frankenstein: What It Means to Be Human." December 17, 2023. https://ivypanda.com/essays/shelleys-frankenstein-what-it-means-to-be-human/.

- To find inspiration for your paper and overcome writer’s block

- As a source of information (ensure proper referencing)

- As a template for you assignment

Academia.edu no longer supports Internet Explorer.

To browse Academia.edu and the wider internet faster and more securely, please take a few seconds to upgrade your browser .

Enter the email address you signed up with and we'll email you a reset link.

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

Download Free PDF

What does it mean to be human? An essay

Related papers

Nursing Philosophy, 2015

Cyborg Persons or Selves, 2019

It would be natural to commence the book dedicated to 'cyborg persons' with broad references to post- and transhumanism. This of course will happen on the following pages, because it is impossible to discuss issues regarding the redefinition of 'human person' without the perspective developed by these branches of contemporary reflection in humanities. Yet I do not consider them as a necessary departing point, because the topic in question is of greater significance than should be confined to one field. Technological enhancement – developments in genetic engineering, artificial intelligence and robotics, and so forth – are processes that are currently happening; we should not be blindsided by them, wondering when they will knock at our door. The question that follows is: how should we refer to the new entities starting to appear among 'us' humans, and what is the significance of redefining of our relationship with these entities (with which we're already familiar, as various parts of 'nature')? Trying to approach that subject we encounter philosophical, sociological, and legal understandings of what it means to be a person – definitions which have never before needed to specify a 'human person'; these are the layers in which we should see a person as existing and operating. Therefore, my principal reference, helping me to rethink the notion of a person in such a way that it may include non-humans (especially cyborg persons) is Joseph Margolis. Particularly helpful to my reasoning is his idea of defining a human person or self as an artefactual individual emergent from the process of hybrid evolution (intertwined nature and culture, due to invention and mastery of language), and everything that this entails with developments of culture and technology (Margolis 2017, pp. 39-62). The stripping of a human person from his assumed, probably 'divine' (or 'of divine provenance') nature or essence, as Margolis does, is bold but bright – not reducing the human world to mere matter, nor blindly accepting neo-Darwinism, but also not accepting religious or transcendental demands. Cultural realism as proposed by Margolis (Margolis 2010, p. 134) seems to be a better weighted version of ontology as proposed by Roman Ingarden (famous pupil of Edmund Husserl) recognizing three ontological realms: material, ideal, and cultural. The entities existing on a cultural level considered by Ingarden were artworks, predominantly novels and sometimes sculptures (Ingarden 1958; 1966). Influenced by his master's transcendentalism and in spite of the discussion on idealism and realism between them, Ingarden claimed that there is an ultimate truth, a correct perception and an objectively correct judgment of aesthetical values of an artwork which have Intentional characteristic – and so he believed that there is one and only one correct form of valuing each artwork (Ingarden 1966). Margolis makes claims much broader than Ingarden's, because he describes the cultural realm as embracing institutions, practices, meanings, ideas, art, languages, and technology. Radically unlike Ingarden, he encloses this in post-Darwinian evolutionary perspective and historical relativism (Margolis 1995). In this realm exists a person, who is an enlanguaged creature involved in an historical social and political life, comparable in ontology to an artwork, because artworks are also enlanguaged entities, artefactual and interpretable, evolving in relation to their matter (Margolis 1999). The way Margolis presents human persons – as artefactual, enlanguaged, and hybrid, having no natural environment and therefore no natural source for any set of norms and rules other than that which is collectively invented, shared, and transformed historically (what he calls “sittlich”) – opens up for the inclusion of cyborgs into the classification of persons. It also opens for consideration the possibilities of cyborgian ethics and politics, because normativity – as Margolis explains – is not rooted in any transcendental setting but rather always contingent and relational. Contemporary discussions on cyborgs and the ethical, social, and political issues that accompany them – currently happening in various places across the world – could benefit from turning to Margolis' philosophy in the process of redefining our ideas of a person, his/her/its/their autonomy, responsibility, and freedom, as well as for imagining possible practical applications in science and politics. It is important to regard some recent occurrences increasing the issue's urgency, such as the presentation of the 'Transhumanist Bill of Rights' to the US Capitol in Washington, D.C. in 2017 by a representative of the Transhumanist Party in favor of life extension and space exploration; or the recognition of Sophie, a humanoid robot produced by Hanson Robotics company from Hong Kong, as an official citizen of Saudi Arabia in 2017. Sophie is the first humanoid to be accepted as a citizen of any country and this has led to discussion on the kind of rights that status brings about, such as whether Sophie can marry, or vote, or if she were intentionally switched off – would that be murder? However I cannot address all the subjects and problems appearing in conjunction with rapidly developing technology, so I limit myself predominantly to the idea of the 'cyborg', a being embodied in a technologically enhanced human form, who by means of online technology implemented in the body has different kinds of perception, cognition, practices, patterns, habits, and/or methods of communicating in comparison to someone embodied in an unaltered human form. Cyborgs are not science fiction, neither they are completely artificial entities as Sophie; there are those on the spectrum between us and robots and androids. These are such persons as Neil Harbisson, whose antenna implanted into his brain allows him to 'hear' colors via bone conduction, and Moon Ribas, whose implanted sensors allow her to 'feel' earthquakes over 1.0 on the Richter scale and movements of the Earth's moon. There are many other DIY bodyhackers too – Harbisson and Ribas are not the first ones to implant themselves with connectivity-enabled technology in order to change their perception and communication. Eduardo Kac implanted his leg with digital memory (in RFID chip form) within the art project 'Time Capsule' in 1997, and Kevin Warwick also implanted himself with multiple chips for sensory perception and online communication. However, in these cases the technology did not merge with the organism in the intent to alter regular performance. For this reason it may be helpful to differentiate between the relatively 'weak' cyborg status of Kac and Warwick, and the relatively 'strong' status of Harbisson and Ribas. Contemplating the changing conditions of personhood nowadays, there should be taken also a broader overlook on the future of society, in which we will have to include differently embodied legal persons – technologically enhanced, genetically engineered, artificially created. An interesting perspective to which I will later refer to more extensively, is proposed by Steven Fuller (a professor of social epistemology and enthusiast of transhumanism) and it is: “Humanity 2.0” – an “Extended Republic of Humanity or Transhumanity” which includes all responsible agents regardless of their material substratum. Humanity 2.0 is Fuller’s name for the republican society inclusive of all possible citizens, not just those born as Homo Sapiens. For this to occur, as he points out, it is necessary to redefine the concept of Human Rights as declared by the United Nations in 1948, which currently limits the basis for civil rights legislation to the Homo Sapiens species (Fuller 2015). Claiming that citizenship and legal rights should not be limited to one kind of biological being, Fuller proposes that we should resign from theological argumentation and its understanding of 'human' as the unique, Abrahamic figure, and instead take an evolutionary approach. In order to test 'human citizenship' he proposes a Turing Test 2.0, in “attempt to capture the full complexity of the sorts of beings that we would have live among us as equals” (Fuller, 2015, p. 81). This kind of proposal has extraordinary effect – according to this line of thinking: “some animals and androids may come to be eligible for citizenship, while some humans may lose their citizenship, perhaps even in the course of their own lifetime” (Fuller 2013, p. 2). For Fuller however the biological human is not inviolate, and “the predicate human may be projected in three quite distinct ways, governed by (...) ecological, biomedical, and cybernetic interests.” (Fuller 2013, p. 6) Moreover, the predicate 'human' is not essential; of main import is extended citizenship and science’s “political capacity to organize humanity into a project of universal concern” (Fuller 2013, p. 5), allowing for responsibility, risk-taking, and pursuing the individually diverse lives of differently embodied persons. Therefore, my research on cyborgs as persons focuses on philosophical redefinition of the category of 'person' with Margolis as an ally, in order to make space for the inclusion of differently embodied, relatively autonomous individuals into our societies and sketch a vision for our future – indispensably framed by sociopolitics as envisioned by Fuller.

In the modern world an individual deals with different technologies and products of scientific and technological progress and becomes more and more dependent on them, spending considerable time to understand changes and to keep up with progress. In general, the entire human history especially in the last few centuries is the history of victories and triumph of science, technology, and information technologies. Moreover, the humankind being a father of technology at the same time became more and more dependent on it. Today technologies penetrate almost every aspect of our life: private, family and intimate, as well as our mentality. But even more serious transformations are awaiting us in the future when devices and technologies are introduced into the human body and consciousness thus putting strain on all our biological (nervous, physical, and intellectual) adaptive capacities. Today they give a serious thought to seemingly strange ideas about whether mobile phones, computers, and organizers can become a part of our body and brain. In fact, technology has become one of the most powerful forces of development.

Culture & Psychology, 1998

Technological artefacts that only twenty years ago were but evocative objects have now become ordinary presences in our life: from artificial implants to mass cosmetic surgery and body manipulation, from new forms of permanent media interconnection to interaction with artificial intelligences. Hence a number of new crucial questions arise, related to our living together in the age of post-humanism. Nowadays, when technology is no longer a tool, or even just an environment, but is wearable and incorporated, and can act retroactively on the very structure of the organism, what are the main challenges we have to face, and the main narratives for making sense of this new human condition? In the tradition of the journal, this special issue addresses the topic from different theoretical perspectives and disciplinary fields. Contributions are divided in three sections: 1) The post-human condition: living in a brave new world'. The essays in this section embrace different ambits relevant to the public sphere and our life together, such as politics, work, religion, fashion, literature. 2) Bodies in question/questioning bodies: here the main focus is on the redefinition of the ableism-disability relationship (and the resulting problematic redefinition of 'ableism' itself) in the light of the typical post-human question of healing-enhancement. 3) Representations/Imaginaries: here the focus is on the way in which the topos of enhancement has been dealt with by fictional and non fictional texts over time, from early television to cinema up to web series. Cosa significa essere umani nell'era dove una tecnologia pervasiva e sempre più 'incorporata' ha eroso il confine tra natura e cultura? Come le nuove possibilità di potenziamento ridefiniscono l'idea stessa di normalità? Quali implicazioni sul nostro vivere insieme? Come porre, se è il caso, la questione del limite? Quali forme narrative concorrono alla costruzione degli immaginari su questi temi? Nella tradizione della rivista, il monografico affronta questo intreccio di questioni a partire da diverse prospettive e diversi ambiti disciplinari. I contributi sono suddivisi in tre sezioni che riguardano alcuni cambiamenti significativi nella sfera pubblica, la ridefinizione dell'idea di 'normalità' relativamente al corpo, gli immaginari legati al tema del 'potenziamento'.

How the Merging of Cyberspace and Real Space is Changing us (into cyborgs), 2012

"The times are changing and so are the people. This always was and always shall be. We are currently witnessing one of the biggest leaps in history in terms of changes in the social environment, influenced by the exponential development of information technology. Social space is changing fast, and with the growth of new media, new features are added to real space and people’s perception of it. What was once called cyberspace is slowly invading real physical space and so, by merging these two, the entire living environment is changing. This goes beyond just a slight shift in the perception of social and/or organizational changes in people’s life: it is a change in the way life is lived on a daily basis. This paper focuses on the changes people are facing in their everyday life, into the realm of the mediated world. It shows how, with the rapid development of informational and communication technologies, the cyberspace is merging with the real space, thus creating a new living environment which consequently changes people’s behaviour. Augmented reality becomes the real reality and people are constantly living in a life-mix of the two worlds (analogue and digital), which are gradually becoming one. this research also presents a perspective on the future development of information and communication technologies, along with current improvements in the field which enabling this. This future is called the Internet of things, and presents a place where everyone and everything is constantly connected, updated, tracked down and located. Such a future depends not only on the technology but also on acceptance by people, so an overview of current changes in people’s behavior, bringing them closer to this acceptance, is presented. Finally, the research draws a parallel between some instances of human behavior in the wave of the new mediated environment and the characterising features of the cyborg definition."

Artificial Culture is an examination of the articulation, construction, and representation of "the artificial" in contemporary popular cultural texts, especially science fiction films and novels. The book argues that today we live in an artificial culture due to the deep and inextricable relationship between people, our bodies, and technology at large. While the artificial is often imagined as outside of the natural order and thus also beyond the realm of humanity, paradoxically, artificial concepts are simultaneously produced and constructed by human ideas and labor. The artificial can thus act as a boundary point against which we as a culture can measure what it means to be human. Science fiction feature films and novels, and other related media, frequently and provocatively deploy ideas of the artificial in ways which the lines between people, our bodies, spaces and culture more broadly blur and, at times, dissolve. Building on the rich foundational work on the figures of the cyborg and posthuman, this book situates the artificial in similar terms, but from a nevertheless distinctly different viewpoint. After examining ideas of the artificial as deployed in film, novels and other digital contexts, this study concludes that we are now part of an artificial culture entailing a matrix which, rather than separating minds and bodies, or humanity and the digital, reinforces the symbiotic connection between identities, bodies, and technologies.

Perspectives in Biology and Medicine, 2003

CLCWeb: Comparative Literature and Culture, 2000

Revista IDEC Patrimonio, 2022

Sosyal Bilimlerde Yeni Egilimler, ed. Lutfi Sunar, Nobel Yay. Ankara, ss. 39-102, 2015

Nationalities Papers, 2013

Journal of Indian Philosophy

جوزف قزي: الحياة الرهبانية جزءان, 2008

Photonics and Nanostructures - Fundamentals and Applications, 2016

Clinical Neurology and Neurosurgery, 2021

Siyaset Sosyolojisi, 2024

Rural and Remote Health, 2018

Leksika/Leksika (Purwokerto. Online), 2024

Thēmis Revista De Derecho, 2004

Journal of Hydrology, 2016

Limnology and Oceanography, 2001

Related topics

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

- Find new research papers in:

- Health Sciences

- Earth Sciences

- Cognitive Science

- Mathematics

- Computer Science

- Academia ©2024

Understanding the Essence of Human Existence

This essay about the definition of a human being explores the complex nature of human existence through biological, philosophical, and existential lenses. It begins by outlining the biological classification of humans as Homo sapiens, noting their cognitive abilities and use of complex language. The discussion then moves to philosophical considerations, emphasizing humans’ unique capacity for consciousness, self-awareness, and moral reasoning. Existentially, the essay highlights humans’ perpetual search for meaning, their creative impulses, and the importance of social connections and community. It argues that being human transcends mere biological aspects, incorporating the depths of consciousness, morality, creativity, and the fundamental need for relationships. The essay concludes by acknowledging the evolving nature of what it means to be human, suggesting that our understanding of humanity is continually redefined by societal changes and advancements in knowledge, reflecting the adaptability and resilience of the human spirit.

How it works

Defining what constitutes a human being is a task that has intrigued philosophers, scientists, and thinkers for centuries. At its core, the definition of a human being encompasses biological, philosophical, and existential dimensions, each contributing to a multifaceted understanding of humanity’s place in the universe. This exploration seeks to navigate through these perspectives, offering insights into the essence of human existence beyond mere biological classification.

Biologically, human beings are identified as Homo sapiens, a species of primates characterized by advanced cognitive abilities, the use of complex language, and the capability for abstract reasoning and problem-solving.

This scientific definition, however, only scratches the surface of what it means to be human. It delineates the physical parameters but does not address the richer layers of consciousness, emotion, and social connectivity that define human life.

Philosophically, the definition of a human being delves into the realms of consciousness, self-awareness, and morality. Humans are not only aware of their existence but can also contemplate their mortality, ponder the universe’s vastness, and question the meaning of their lives. This capacity for introspection and the pursuit of knowledge and truth distinguishes humans from other species. Furthermore, humans possess a moral compass, an inherent understanding of right and wrong, which guides their actions and interactions within society. This moral dimension adds depth to our understanding of humanity, highlighting the role of ethics and values in shaping human behavior and societal norms.

Existentially, to be human is to engage in the perpetual search for meaning and purpose. Unlike any other species, humans have the ability to create, imagine, and innovate, driven by an insatiable curiosity about the world and a desire to leave a mark on it. This creative impulse leads to the development of art, literature, science, and technology, reflecting humanity’s diverse ways of interpreting and altering their environment. Moreover, humans are inherently social beings, seeking connection, love, and community. Relationships and social bonds are fundamental to human well-being, providing a sense of belonging and identity.

However, the definition of a human being is also marked by its ambiguity and fluidity, evolving with societal changes and advancements in knowledge. The boundaries of what it means to be human are continually being pushed and redefined, challenging previous understandings and opening new avenues for exploration. This dynamic nature of the human definition reflects the adaptability and resilience of humans, their capacity to grow and change in the face of challenges and discoveries.

In conclusion, the definition of a human being transcends biological classification, encompassing the complexities of consciousness, morality, creativity, and social connectivity. It is a reflection of humanity’s unique place in the natural world, characterized by an unending quest for meaning, knowledge, and connection. Understanding the essence of human existence requires a multidimensional approach that appreciates the depth and diversity of the human experience. As society progresses and knowledge expands, the definition of what it means to be human will continue to evolve, highlighting the infinite potential and mystery that lie at the heart of human nature.

Cite this page

Understanding the Essence of Human Existence. (2024, Apr 01). Retrieved from https://papersowl.com/examples/understanding-the-essence-of-human-existence/

"Understanding the Essence of Human Existence." PapersOwl.com , 1 Apr 2024, https://papersowl.com/examples/understanding-the-essence-of-human-existence/

PapersOwl.com. (2024). Understanding the Essence of Human Existence . [Online]. Available at: https://papersowl.com/examples/understanding-the-essence-of-human-existence/ [Accessed: 9 Nov. 2024]

"Understanding the Essence of Human Existence." PapersOwl.com, Apr 01, 2024. Accessed November 9, 2024. https://papersowl.com/examples/understanding-the-essence-of-human-existence/

"Understanding the Essence of Human Existence," PapersOwl.com , 01-Apr-2024. [Online]. Available: https://papersowl.com/examples/understanding-the-essence-of-human-existence/. [Accessed: 9-Nov-2024]

PapersOwl.com. (2024). Understanding the Essence of Human Existence . [Online]. Available at: https://papersowl.com/examples/understanding-the-essence-of-human-existence/ [Accessed: 9-Nov-2024]

Don't let plagiarism ruin your grade

Hire a writer to get a unique paper crafted to your needs.

Our writers will help you fix any mistakes and get an A+!

Please check your inbox.

You can order an original essay written according to your instructions.

Trusted by over 1 million students worldwide

1. Tell Us Your Requirements

2. Pick your perfect writer

Your complimentary articles

You’ve read one of your four complimentary articles for this month.

You can read four articles free per month. To have complete access to the thousands of philosophy articles on this site, please

Being Human

By grant bartley.

What is it like to be a human being? There’s one sense in which you already know the answer, of course: your life shows you what it’s like to be a human being. But how would you describe what that life is like? And what universal truths about human life does your experience reveal? What would we say about the human condition if we were to assiduously analyse it? I suggest we can’t answer these questions as well as we’d like to assume.

Science has spawned a whole line of sub-disciplines investigating the nature of human beings – sociology, anthropology, psychology, neurology etc – displaying a spectrum of success, and we may hope, all with bright futures. But even if science were to evolve a sound comprehensive theory of the laws governing human behaviour, this would tell only a quarter of the human story, at most. That is to say, science can describe and test the processes which make us who and what we are, but it does not tell us what is it like to live life. This is because it doesn’t ask the right questions – nor can it.

Aristotle distinguished between four kinds of causes, and scientific explanations describe what he called ‘efficient causes’. This means that they can tell us about how we came to be what we are now, and how the processes which produced us continue to act. But in asking what human life is like, we’re instead asking, ‘What is the nature of human experience? How can we describe the contents of experience?’

Novels and other types of art reflect our experience of life, for sure; but not in a systematic way. As usual, philosophers have led the effort to get truly systematic knowledge. The attempt to systematically describe what it is like to experience is called phenomenology . Phenomenology as a philosophical project was begun in the late 19th and early 20th century, most famously Continentally, by Brentano and Husserl. When phenomenology was combined with ethics and (bad) metaphysics it became known as existentialism. Heidegger and Sartre are the most infamous exponents of that souped-up way of describing what human being is like. Unfortunately, there does not seem to be any consensus existentialist understanding of human experience, so we can say that, as yet, there is little sure knowledge in existentialism’s descriptions – only lots of highly-convoluted opinions. Existentialism is like philosophical spaghetti, so far.

In Aristotle’s scheme, to ask about the nature of something at any given point in time (‘what it’s made of’) is to ask for its ‘material cause’. This is an unfortunate label when we’re enquiring into the immediate nature of experience , I think. Aristotle had two other types of causes, one of which he called the ‘formal cause’. A formal explanation of x answers the question, ‘What does [word/concept] x really mean?’ It gives the sort of explanation of something which might be found in a perfectionist’s dictionary, I might say.

Formal explanations are what analytical philosophy does best. That is to say, it explores and critiques our understanding of concepts, and so is a formal type of explanation. Philosophy has performed this sort of enquiry ever since Socrates in the 5th century BC.

What use is philosophy? Conceptual analysis can make significant contributions to our understanding of being human. Consider the concept of addiction , for example – as Piers Benn does. He argues that the popular use of this concept deceptively implies a helplessness which distorts people’s understanding of the behaviour tagged by that word. So the meaning of this concept potentially has political implications for global society. Conceptual analysis also tells us how to be cool , how we might be happy too. Jeffrey Gordon and Mark Weeks show how the analytical method can be applied to understand even humour. Mark’s analysis also incorporates the phenomenology of laughter: what it means to experience the transformation effected by the sort of laughter where you forget yourself, just for a moment. Analytical philosophy’s examination of aspects of the human condition can evidently be very useful.

Piers’ consideration of addiction, I think, also shows us how easily our understanding might be bewitched by our abuse of words or misunderstanding of concepts. This implies we’d be enlightened by our words being brought into ‘good form’, as one could say – that is, if we gain the sort of sound formal understanding of our concepts which analytical philosophy seeks. We only very lightly paddle the surf at the shores of human truth in this issue. A more systematic formal understanding of the human condition would start by analysing the concept ‘human being’, and continue analysing through the uncovered subcategories. It would ask, for instance, what does it mean to be joyful, melancholy, angry, ecstatic – all the emotions that flesh is heir to? What indeed is an emotion; and how does it differ experientially from a ‘mere’ idea, for instance?

Aristotle’s fourth kind of way of explaining things is called the ‘final cause’. To give this kind of explanation is to explain a thing’s purpose , or you could say, the goal which is its function to achieve. The question of the purpose of human life is a whole other issue, then… This issue, meanwhile, is permeated with diverse reflections on the human condition. I trust you will find it a delightful and enlightening way of experiencing what it’s like to be a human being.

Advertisement

This site uses cookies to recognize users and allow us to analyse site usage. By continuing to browse the site with cookies enabled in your browser, you consent to the use of cookies in accordance with our privacy policy . X

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

At the heart of being human is the quest for meaning and the desire to leave a lasting impact. From the pursuit of knowledge and understanding to the creation of art and innovation, humans strive to contribute to a greater narrative that transcends their own lifetimes.

What does it mean to be human? Or, putting the point a bit more precisely, what are we saying about others when we describe them as human?

Being Human is a major new season launching on BBC Earth that aims to take us as closer to understanding who we are. Why do we behave the way we do? How do we live better?

If ‘human’ means ‘my own natural kind,’ then referring to a being as human boils down to the assertion that the other is a member of the natural kind that the speaker believes herself to be.

Part of what it means to be human is how we became human. Over a long period of time, as early humans adapted to a changing world, they evolved certain characteristics that help define our species today.

Shelley’s Frankenstein: What It Means to Be Human Essay. Exclusively available on Available only on IvyPanda® Made by Human • No AI. Frankenstein, a ground-breaking novel by Mary Shelley published in 1818, raises important questions about what it means to be human.

In this essay I will argue that researching into what it means to ‘be human’ is a quite complex task, because of the varied theoretical concepts involved in this idea. In order to support my statement, I will give examples of how ‘Blade Runner’ and relate this to different theoretical frameworks I will discuss across the essay.

human being, a culture-bearing primate classified in the genus Homo, especially the species H. sapiens. Human beings are anatomically similar and related to the great apes but are distinguished by a more highly developed brain and a resultant capacity for articulate speech and abstract reasoning.

This essay about the definition of a human being explores the complex nature of human existence through biological, philosophical, and existential lenses. It begins by outlining the biological classification of humans as Homo sapiens, noting their cognitive abilities and use of complex language.

by Grant Bartley. What is it like to be a human being? There’s one sense in which you already know the answer, of course: your life shows you what it’s like to be a human being. But how would you describe what that life is like? And what universal truths about human life does your experience reveal?