- Study protocol

- Open access

- Published: 21 July 2021

Medical Assistance in Dying in patients with advanced cancer and their caregivers: a mixed methods longitudinal study protocol

- Madeline Li ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-3977-7437 1 , 2 na1 ,

- Gilla K. Shapiro ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-2214-8263 1 , 3 na1 ,

- Roberta Klein 1 ,

- Anne Barbeau 1 ,

- Anne Rydall ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-4692-9101 1 ,

- Jennifer A. H. Bell ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-3617-6852 1 , 2 , 4 ,

- Rinat Nissim ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-3624-5806 1 , 2 ,

- Sarah Hales ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-6404-8124 1 , 2 , 3 ,

- Camilla Zimmermann ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-4889-0244 1 , 2 , 3 , 5 ,

- Rebecca K. S. Wong 1 , 6 &

- Gary Rodin ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-6626-6974 1 , 2 , 3

BMC Palliative Care volume 20 , Article number: 117 ( 2021 ) Cite this article

7228 Accesses

6 Citations

7 Altmetric

Metrics details

The legal criteria for medical assistance in dying (MAiD) for adults with a grievous and irremediable medical condition were established in Canada in 2016. There has been concern that potentially reversible states of depression or demoralization may contribute to the desire for death (DD) and requests for MAiD. However, little is known about the emergence of the DD in patients, its impact on caregivers, and to what extent supportive care interventions affect the DD and requests for MAiD. The present observational study is designed to determine the prevalence, predictors, and experience of the DD, requests for MAiD and MAiD completion in patients with advanced or metastatic cancer and the impact of these outcomes on their primary caregivers.

A cohort of patients with advanced or metastatic solid tumour cancers and their primary caregivers will be recruited from a large tertiary cancer centre in Toronto, Ontario, Canada, to a longitudinal, mixed methods study. Participants will be assessed at baseline for diagnostic information, sociodemographic characteristics, medical history, quality of life, physical and psychological distress, attitudes about the DD and MAiD, communication with physicians, advance care planning, and use of psychosocial and palliative care interventions. Measures will subsequently be completed every six months and at the time of MAiD requests. Quantitative assessments will be supplemented by qualitative interviews in a subset of participants, selected using quota sampling methods.

This study has the potential to add importantly to our understanding of the prevalence and determinants of the DD, MAiD requests and completions in patients with advanced or metastatic cancer and of the experience of both patients and caregivers in this circumstance. The findings from this study may also assist healthcare providers in their conversations about MAiD and the DD with patients and caregivers, inform healthcare providers to ensure appropriate access to MAiD, and guide modifications being considered to broaden MAiD legislation and policy.

Peer Review reports

Following the decision of the Supreme Court of Canada on February 6, 2015 to decriminalize medical assistance in dying (MAiD), [ 1 ] the Federal Parliament of Canada passed Bill C-14 on June 17, 2016 to establish the legal eligibility criteria for MAiD. These criteria included the presence of a serious and incurable medical condition, an advanced state of irreversible decline in capability, enduring and intolerable physical or psychological suffering, and a reasonably foreseeable natural death [ 2 ]. Bill C-14 excluded mature minors or those with mental illness as the sole underlying medical condition. Legislative review of these criteria are now underway, and the passage of Bill C-7 on March 17, 2021 removed the requirements of a "reasonably foreseeable natural death" [ 3 , 4 ].

Over 21,500 people in Canada chose to end their lives through assisted dying in the first five years of MAiD, more than 67% of whom had advanced cancer [ 4 ]. The frequency of MAiD in Canada is increasing annually, [ 5 ] although the overall proportion of medically assisted deaths is in the middle of the international rates reported. These range from 0.3% of deaths in Oregon, United States, to 4.6% in the Netherlands [ 4 , 6 ]. In 2019, MAiD deaths in Canada represented approximately 2.5% of all deaths, [ 4 ] and 6.3% of cancer-related deaths [ 4 , 7 ]. Footnote 1

In 2007, we completed a longitudinal study of the desire for death (DD) in individuals with advanced cancer [ 8 ]. This early research confirmed that the DD occurs on a continuum from the passive wish that the end would come earlier than it would otherwise naturally occur, referred to as the desire for hastened death (DHD) or the wish to hasten death (WTHD), [ 9 , 10 , 11 ] to a more active desire to end life, reflected in requests for MAiD [ 12 ]. The DD is uncommon in patients with advanced cancer receiving active treatment, [ 8 ] but is reported in up to half of all individuals in palliative care, [ 13 , 14 , 15 ] and may paradoxically coexist with the will to live [ 16 ]. This paradox underlines the complexity of psychological states related to the DD and the importance of reflective conversations before action on such wishes is taken [ 17 ].

Research examining attitudes and correlates of the WTHD in patients with advanced cancer has largely been cross-sectional, retrospective or conducted in settings where assisted dying is not permitted [ 18 , 19 , 20 , 21 , 22 ]. In research conducted in palliative care settings, a transient WTHD was found in 11–55% of patients, while 3–20% reported a more pervasive and persistent wish to die [ 13 ]. In a Canadian survey of 377 cancer patients with a prognosis of less than six months, Wilson and colleagues [ 13 ] found that almost 70% reported no WTHD, more than 18% acknowledged a transient WTHD, and over 12% reported a clear and persistent WTHD on the Desire for Death Rating Scale [ 14 ]. These findings are consistent with our previous study in which more than 65% of patients with advanced cancer indicated they wanted to continue living regardless of the pain or suffering that their disease might cause, and only 1.2% reported a clear WTHD on the Schedule of Attitudes towards Hastened Death (≥10) [ 8 ]. This difference between the two studies is likely due to the Wilson study sampling patients closer to the end of life, whereas we studied ambulatory patients recruited from oncology clinics.

Studies have also found that the DD fluctuates widely over time, [ 8 , 14 , 23 , 24 ] even during the last two weeks of life [ 25 ]. In a sample of almost one thousand American patients with advanced disease, Emanuel and colleagues found that more than 10% reported seriously considering assisted death for themselves. However, on follow-up two to six months later, approximately half had changed their minds, and an almost equal number who had not initially been interested in assisted death were then considering it [ 26 ].

The DD in patients with advanced cancer may arise from a complex interaction of factors, such as the experience or fear of uncontrolled physical or psychological suffering, the wish to maintain a sense of personal autonomy, or the desire to avoid burdening others (Fig. 1 ) [ 27 , 28 ]. It has also been associated with pain, high disease burden, low self-esteem, poor spiritual well-being, attachment insecurity, being unmarried, younger age, and having a history of psychiatric illness [ 18 , 25 , 26 , 29 , 30 , 31 , 32 ]. Some of these factors, such as those related to self-esteem, spiritual well-being, and attachment security, may be modifiable through specific psychotherapies, such as Managing Cancer and Living Meaningfully, [ 33 ] a brief, supportive-expressive intervention developed by our team and now being delivered internationally. Attachment security refers to an individual’s expectations and preferences regarding support from significant others in times of need and the capacity to make use of such support to relieve distress [ 34 ]. A secure attachment style, reflecting comfort with closeness and reliance on others, has been shown to protect against depression in cancer patients [ 35 ]. An avoidant attachment style, characterized by inflexible self-reliance, the need for personal control, and reluctance to accept support from others, has been associated in cancer patients with problematic relationships with oncologists [ 36 ] and requests for assisted dying [ 30 , 37 ].

MAiD, Medical Assistance in Dying; WTHD, Wish to Hasten Death

Physical symptom burden has been found to predict the DD [ 8 , 26 , 29 ] in patients with advanced cancer, although the motivation for MAiD in those who request and receive it is more often related to the loss of meaning, autonomy, and identity [ 19 , 38 , 39 ]. Some studies have found that religious observance and religious denomination have been linked to attitudes about assisted dying [ 40 , 41 ]. The influence of social and demographic factors on MAiD requests also deserves further exploration. Research thus far indicates that MAiD completion is more common in those who are older, Caucasian, more highly educated, and more affluent [ 38 , 39 ].

Dramatic changes have occurred over the past decade in Canada and throughout the world in public attitudes and expectations about death and dying, in access to psychosocial and palliative care for cancer patients, and, most recently, in the availability of MAiD. These changes may increase the likelihood that individuals with advanced disease and their caregivers will reflect upon and communicate the DD, engage in advance care planning, or consider actions to end their lives. While patients who request MAiD most often have access to specialized palliative care in settings where this is available, [ 4 , 42 , 43 ] the extent to which early palliative and supportive care interventions and empathic communication with healthcare providers about the goals of care at the end of life can affect the DD and requests for MAiD is unknown. Further, although caregivers are likely to be affected by patients’ DD and MAiD requests, [ 44 , 45 , 46 , 47 , 48 , 49 ] there is only limited research evaluating their experiences and support needs in these circumstances [ 20 , 26 , 48 ].

Caregivers typically experience a dramatic change in their daily lives and roles following the diagnosis of cancer or advanced disease in a loved one, related to the loss of family income [ 48 ] and the requirements for practical, social, and emotional support [ 47 , 49 ]. They must often shoulder the physical and psychological burden of caregiving, while also facing the suffering and threat of mortality in their loved one, their own fear of facing the future alone, and the financial strain caused by the illness. Although decisions about assisted dying may have an impact on primary caregivers, we know relatively little about the impact of their distress on the emergence and persistence of the DD and MAiD requests in patients with advanced cancer [ 50 ]. Understanding the experience of caregivers in relation to MAiD is therefore an important area in need of further research.

Optimal end-of-life care for patients with advanced cancer requires healthcare providers to engage in conversations with those who express a DD and/or who request MAiD. Cross-sectional research has identified some factors associated with the DD and MAiD requests, but it is not possible from such studies to distinguish confounding from correlational and causal factors, or to determine the course of an individual’s desire for MAiD in the face of advanced cancer.

We will be conducting a longitudinal study to examine the prevalence, trajectory, predictors, and nature of the desire for MAiD in a geographic setting where MAiD is legally available. The goals of this mixed methods study are to estimate the prevalence of the DD in patients with advanced cancer; to understand the trajectory and contributors to the DD, MAiD requests and MAID completion; and to elucidate the experience and support needs of their primary caregivers. The findings of this study could inform the training of healthcare providers regarding conversations with patients with advanced cancer and their caregivers about goals of care at the end of life, the DD, and MAiD as well as psychotherapeutic conversations about the DD. This information will also support the review of legislation to ensure appropriate access to MAiD.

To determine in patients with advanced cancer:

The prevalence of the DD, MAiD requests, and MAiD completions.

The trajectory and predictors of the DD, MAiD requests, and MAiD completions.

To examine the predictors of distress in primary caregivers of patients with advanced cancer.

Study design

This research is a prospective, longitudinal, mixed methods study conducted with patients with advanced or metastatic cancer and their primary caregivers. This study was approved on September 2, 2020, by the University Health Network Research Ethics Board (UHN REB #18–6182), and all participants will provide informed consent. Any protocol amendments will be submitted to the UHN REB for approval, and important changes that could impact participants’ willingness to continue in the study will be communicated to them in a timely manner. Data collection is expected to begin by January 2021.

Participants and setting

We plan to retain a longitudinal cohort of 600 patients with advanced or metastatic cancer and 300 of their primary caregivers recruited from the outpatient medical oncology clinics at the Princess Margaret Cancer Centre (PM), University Health Network, in Toronto, Canada’s largest comprehensive cancer treatment, education and research centre. This sample size is required to test our proposed regression model for predictors of MAiD requests and completions (Fig. 1 ), in which we will need at least 110 patients with at least two data points (baseline and one follow-up) [ 8 ], based on five to ten observations required for each of the 11 predictors included in our SEM [ 51 ]. Given that MAiD accounts for almost 5% of cancer deaths, and this represents 26% of MAiD requests at PM [ 39 ], we estimate ~ 115 subjects requesting MAiD and ~ 30 subjects receiving MAiD among 600 recruited patients.

To accommodate an anticipated 25% drop-out rate, we will recruit 800 patients and 400 primary caregivers over approximately 3.5 years for a final sample size of 600 patients and 300 primary caregivers. This is feasible given that PM provides care for approximately, 3200 Stage III or IV cancer patients per year, 60% of whom are expected to meet inclusion criteria; a conservative estimate is that 50% will provide informed consent, yielding approximately 960 eligible and consenting participants per year.

Participant recruitment and eligibility

Patients will be included if they: 1) are age 18 years or older; 2) are able to speak and read English sufficiently well to provide informed consent and complete questionnaires and/or interviews; and 3) have been diagnosed with advanced or metastatic solid tumour cancers of any type. Exclusion criteria will include: 1) significant cognitive impairment documented in their medical record or indicated by a score of < 20 on the Short Orientation-Memory-Concentration Test (SOMC); and 2) lack of sufficient proficiency in the English language to provide informed consent and complete the questionnaires and/or interviews. Trained research personnel will conduct the informed consent discussion with eligible and interested patients. Eligible patients who decline to participate will be asked their permission to allow the research team to document basic demographics to allow for later assessment of generalizability. Participants who begin the study will be considered withdrawn if they are later unable to participate due to a deterioration in cognitive functioning or physical capacity.

Individuals identified by participants as their primary caregivers will be approached by research personnel for recruitment if they are: 1) age 18 years or older; and 2) able to speak and read English sufficiently well to provide informed consent and complete questionnaires and/or interviews. A primary caregiver may be the spouse or partner of the patient, a relative or other family member, or a close friend. Caregivers may continue to participate in this study even if the patient participant subsequently withdraws from the study.

Study measures

Questionnaire package.

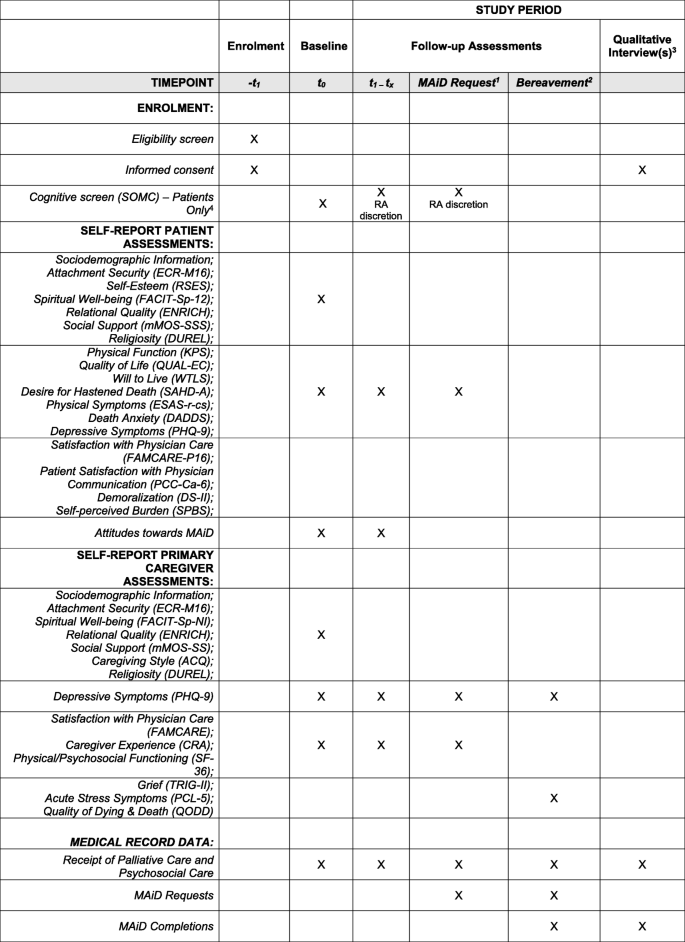

At baseline, patients and caregivers will complete both sets of baseline-only and follow-up measures. All participants will provide sociodemographic information at baseline. The Short Orientation-Memory-Concentration Test (SOMC) [ 52 ] will be conducted with patients at baseline in order to test patient’s cognitive function; this measure may be repeated at follow-up at the discretion of the research assistant. See Tables 1 and 2 for a description of the key study measures listed below, and Fig. 2 for the schedule of participant assessments.

1 If a patient requests MAiD during the study, even if it falls between the 6 monthly scheduled time points, the patient and their primary caregiver (if applicable), will be invited to complete a follow-up assessment and a qualitative interview at this time. 2 In the event that a patient dies during the study (whether by MAiD or other causes), the patient’s primary caregiver (if applicable), will be approached within 6 months of the patient’s death to complete a final follow-up bereavement assessment and a qualitative interview. 3 In addition to qualitative interviews with patients requesting MAiD and their participating caregivers, and bereavement interviews with participating caregivers whose loved ones die during the study, a subset of participants (patients and caregivers) will be identified through purposeful sampling and invited to complete one or more qualitative interview(s) at the 6 monthly follow-up time points over the course of the study. 4 The SOMC may be re-administered at the discretion of the study research assistant if they feel the patient’s cognitive status may be impaired or have declined since the previous assessment. In the event that a patient fails a cognitive screen during the study, they will be withdrawn by the study principal investigator

Patient Baseline-Only Measures : Attachment Security: Brief Modified Experiences in Close Relationships scale (ECR-M16) [ 89 ]; Spiritual Well-being: Functional Assessment of Chronic Illness Therapy-Spiritual Well-Being scale (FACIT-Sp-12, 58) Relational Quality: ENRICH Marital Satisfaction Scale (ENRICH) [ 74 ]; Social Support: The modified Medical Outcomes Study Social Support Survey (mMOS-SSS) [ 75 , 76 ]; Religiosity: The Duke University Religion Index (DUREL) [ 77 ]; and, Self-Esteem : The Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale (RSES) [ 64 ].

Patient Baseline and Follow-up Measures: Physical Function: The Karnofsky Performance Status index (KPS) [ 53 , 54 ]; Quality of Life: The Quality of Life at the End of Life Scale-Cancer scale (QUAL-EC) [ 55 , 56 ]; Will to Live: The Will to Live Scale (WTLS) [ 57 ]; Desire for Hastened Death: The Schedule of Attitudes towards Hastened Death–Abbreviated (SAHD-A) [ 58 ]; Depressive Symptoms: Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9) [ 59 ]; Physical Symptoms: Edmonton Symptom Assessment System-Revised, including constipation and sleep disturbance (ESAS-r-cs) [ 60 , 61 , 62 ]; Death Anxiety: Death and Dying Distress Scale (DADDS) [ 65 , 66 , 67 ]; Patient Satisfaction with Physician Communication: Patient-Centered Communication-Cancer-6 items (PCC-Ca-6) [ 68 ]; Satisfaction with Physician Care: Modified FAMCARE Scale – Patient-16 items (FAMCARE-P16) [ 63 ]; Demoralization: Demoralization Scale-II (DS-II) [ 70 , 79 ]; and, Self-Perceived Burden: Self-Perceived Burden Scale (SPBS) [ 71 ]. Participants will also answer several questions to assess their attitudes towards MAiD.

Caregiver Baseline-Only Measures: Attachment Security: Brief Modified Experiences in Close Relationships scale (ECR-M16) [ 89 ]; Spiritual Well-being: Functional Assessment of Chronic Illness Therapy-Spiritual Well-Being–Non-illness version (FACIT-Sp-NI) [ 72 , 73 ]; Relational Quality: ENRICH Marital Satisfaction Scale (ENRICH) [ 74 ]; Social Support: The modified Medical Outcomes Study Social Support Survey (mMOS-SSS) [ 75 , 76 ]; Caregiving Style: The Adult Caregiving Questionnaire [ 78 ]; Religiosity: The Duke University Religion Index (DUREL) [ 77 ].

Caregiver Baseline and Follow-up Measures: Depressive Symptoms: Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9) [ 59 ]; Satisfaction with Physician Care: FAMCARE Scale (FAMCARE) [ 69 ]; Caregiver Experience: The Caregiver Reaction Assessment scale [ 80 ]; Physical and Psychosocial Functioning: The Medical Outcomes Study Short-Form 36 (SF-36) [ 82 ].

We will also administer measures to caregivers six months post-patient death: Grief: The Texas Revised Inventory of Grief-Part II (TRIG-II) [ 83 , 84 ]; Traumatic Stress Symptoms: The Posttraumatic Stress Disorder Checklist for DSM-5 (PCL-5) [ 85 , 86 ]; Quality of Death: The Quality of Dying and Death questionnaire (QODD) [ 87 ]; and, Depressive Symptoms: Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9) [ 59 ].

Chart Review Form: Patients’ medical records will be reviewed at baseline and at each follow-up in order to document: i) medical diagnosis, date of diagnosis, and current cancer stage; ii) medical history including current comorbid medical and psychiatric diagnoses; iii) treatments received, including the timing of psychosocial oncology and/or palliative care interventions; and iv) emergent DD/suicidality events. We will obtain from the MAID clinical database the reasons of the patient and/or assessor-rated reasons for MAiD requests, MAiD approvals, MAiD completions, and non-completions.

Qualitative Interview: A semi-structured interview will be used. This interview guide will be further developed and reviewed as the constant comparative analysis progresses [ 90 ]; emerging themes in earlier interviews will serve to refine interview questions and probes. Open-ended enquiry will be made in the initial interview to understand the illness experience, including; caregiver stress, burden, support needs and support received, emotional and physical distress; attitudes about MAiD and advance directives. All interviews will be audiotaped, transcribed verbatim, verified and de-identified prior to analysis.

Data collection procedures

Baseline assessment.

Participants will be given the option of taking the questionnaire package home and returning the completed package in a self-addressed stamped envelope or completing it online. Participants will also be provided the option of having the questions read to them by a member of the research team as some participants may require this assistance due to their state of health. Medical data will be extracted from review of the medical record of each patient.

Longitudinal follow-up assessments

Participants will complete follow-up questionnaires every six months until study completion, unless they voluntarily withdraw, are unable to participate due to impairment in cognitive or physical functioning or die. An additional assessment will be made at the time of a MAiD request. Following the assessment, the medical record review will be updated. Where applicable, the date of death will be obtained from the medical record. In the case of patient death, participating primary caregivers will be followed-up approximately six months after this event to complete a bereavement assessment.

Qualitative assessments

Qualitative interviews will be conducted in a subset of the study participants. A quota sampling method [ 51 ] will be used to select a subset of patients and primary caregivers for one or more qualitative interview(s), conducted at six monthly intervals. Purposeful sampling will be based on high and low outcomes on the Schedule of Attitudes towards Hastened Death-Abbreviated (SAHD-A) (for patients) [ 58 ], caregiving burden and distress measures (for caregivers), and sociodemographic representation (for both patients and caregivers). We estimate that the saturation point will be reached at 10–15 participants per group, but we will recruit participants until saturation is reached. A grounded theory approach with constant-comparative analysis [ 90 ] will be used to identify themes and to determine the sample size at saturation point [ 91 ]. The interviews will last up to 60 min, depending upon the participants’ ability to participate, and will be conducted by a trained interviewer at the convenience of the participants over the telephone, in the clinic, or using a UHN-approved online platform. A frequency of six-monthly intervals was chosen in order to minimize participant burden but still capture as much of their longitudinal experience as possible. Enquiry will be made in follow-up interviews about issues raised in the first interview. Should a participating patient request MAiD, they, and their primary caregiver (if applicable), will be invited to complete an interview at that time, even if it falls between scheduled time points. Should a participating patient die during the study, either from MAiD or other causes, their primary caregiver (if applicable) will also be invited to complete one final semi-structured interview approximately six months after the patient’s death.

Data analysis

Survey data.

Descriptive statistics, desegregated by sex and gender, will be calculated to provide summary information about the characteristics of the participants at baseline. For each assessment time, descriptive statistics will be calculated for the DD outcomes and all other predictive variables. Prevalence of the DD, as measured by the SAHD-A, will be compared to our historical dataset [ 92 ]. The distributions of the continuous variables will be examined for non-normality, and transformations will be employed where necessary. Bivariate associations between DD variables and baseline medical and sociodemographic factors, as well as associations of these baseline variables with physical, psychosocial, and psychological risk factors will be described by calculating subgroup means and standard deviations for categorical variables and correlation coefficients for continuous variables.

The analysis of the longitudinal data will be conducted using mixed linear models (MLM), [ 93 ] which can take into account incomplete data and both time-varying and time-invariant predictors. To accommodate anticipated variations in individual profiles, random effects models will be fitted. MLM logistic regression will be used to determine predictors of both MAiD requests and completions. Similar exploratory analyses will be conducted to identify associations with emergent suicidality. We will replicate the MLM analysis from our previous study of the DD, [ 8 ] now incorporating receipt (or not) of psychosocial and/or palliative care interventions, and death anxiety as additional predictors of the DD (Fig. 1 ). To examine the statistical significance of interactions among medical, sociodemographic, physical, and psychosocial factors as suggested by the exploratory analyses, relevant interaction terms will be included in the MLMs. To avoid over-fitting the model, only those interactions regarded as clinically relevant will be tested in the model.

Qualitative interviews

A grounded theory approach will guide the qualitative data collection and analysis [ 94 ]. Conceptual categories and themes for coding will be derived directly from analyzing the interview material, with a view to inspecting deviant or negative cases in order to refine emerging propositions or hypotheses. This iterative process will continue until theoretical saturation is reached. The data analysis will use an inductive, constant comparison method to code or index the data. Once all data that matches that theme have been located, the process will be repeated to identify further themes or categories. Categories will be added to reflect the nuances in the data as possible. Cross-indexing will allow for the analysis of data items that fit into more than one category. Systematic comparative analysis will be used to identify differences and similarities between men and women, and those with and without a high DD (for patients), and with and without high caregiving burden and/or distress (for caregivers). Categories will also be examined in a longitudinal manner to identify patterns of emergence and development of categories over time and these finding will be compared to the quantitative data, particularly for the impact of goals of care conversations on desire for MAiD. Our analysis will be informed by our previous qualitative study on the DD [ 12 ].

Methodological strengths

This project is a longitudinal study of the course, predictors, and nature of the desire for MAiD in patients with advanced cancer in a geographic setting where MAiD is legally available. It includes quantitative and qualitative methods and uses a comprehensive battery of validated scales to measure the physical and psychosocial variables that we hypothesize are associated with the DD and MAiD requests and completions. The large study sample of patients and caregivers is a strength of the study design, enabling the evaluation of hypotheses in sub-groups. The study also will collect a wide range of sociodemographic information, which will enable the evaluation of the social determinants of the DD and MAiD, as well as examination of health equity in the receipt of MAiD. The quality of the research data collected will be ensured by having experienced, trained research personnel follow best research practices and institutional guidelines, including the use of standardized source notes and documentation of study participation in the patient’s clinical research record, to ensure rigour in the data collection processes. Research personnel will employ direct online data entry whenever possible; duplicate data entry for questionnaires completed in hard copy; and verification of transcribed interviews and all data extracted through medical chart review (e.g., disease and treatment-related data, supportive care services data, MAiD clinical data). Processes for confidentiality and secure storage of data have been ensured through REB approval, and data will be retained for 10 years post study completion as per REB guidelines at our institution. Further, all studies at PM are subject to internal audit by the Cancer Clinical Research Unit and/or the UHN Research Quality Integration teams, both of whom are independent of the study team.

Foreseeable limitations and mitigation strategies

The main challenge of this study is the requirement to recruit a large sample of patients with advanced or metastatic cancer and their primary caregivers. However, in our previous research experience with this population, we found that a 60% recruitment rate is achievable, without adverse effects from completion of a battery of measures of this kind [ 8 ]. Although there are a relatively large number of measures, we have minimized participant burden by limiting the number of measures administered longitudinally, selecting measures that are relatively brief or have been shortened from their original versions, offering the option of printed copy and online questionnaire completion at the hospital or at home, providing assistance with completion of questionnaires as requested in-person, online, or over the telephone, and conducting the qualitative interviews at the participants’ convenience. Participants with significant suicidality, physical or emotional distress identified by the research staff will be offered referral for psychosocial oncology and palliative care services in the Department of Supportive Care at PM, with notification to the attending oncologist with the patient’s consent. For caregivers (including bereaved caregivers) who express significant distress when completing the measures or qualitative interviews, a referral to the Department of Supportive Care’s Caregiver Clinic at PM for bereavement and/or psychosocial support will be offered.

Knowledge translation

Integral to the goals of this study is knowledge translation in the form of training healthcare providers to respond appropriately to expressions of the DD from patients in this new era of MAiD. Our findings will be directly incorporated into UHN MAiD training workshops, invited speaker engagements and the UHN MAiD website, to inform MAiD teams. Dissemination will occur through publications and conference presentations locally, nationally, and internationally, and as well as via the website of the Global Institute of Psychosocial, Palliative and End-of-Life Care (GIPPEC; see www.gippec.org ) and the Canadian Association of MAiD Assessors and Providers (CAMAP; see camapcanada.ca), thus bridging the knowledge to action gap.

Study implications

Data from this study will contribute significantly to our understanding of the DD in a setting where MAiD is legal, and inform critical questions regarding the utility of advance directives for MAiD, the management of depression in MAiD assessment, and how to guide healthcare providers in responding to DD statements with advanced cancer patients. The findings from this study will inform the training of oncologists and other healthcare providers in conversations about the DD and MAiD, and the assessment for MAiD eligibility through identifying distinctions between the DD, depressive suicidality, and the desire for MAiD in patients with advanced cancer. The results will also provide an evidence base to inform proposed changes in MAiD legislation, including the potential permissibility of MAiD in mental illness and as an advance directive.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets to be generated and/or analysed during the current study will not be publicly available due to institutional privacy and confidentiality guidelines. Additional information may be available from the corresponding authors on reasonable request.

The percentage of total cancer-related deaths in Canada was calculated by dividing MAID-related cancer deaths in 2020 (5,248) [ 4 ] by total cancer deaths in 2020 (83,300) [ 7 ].

Abbreviations

Caregiver Reaction Assessment scale

Death and Dying Distress Scale

Desire for Death

Desire for Hastened Death

Demoralization Scale-II

Diagnostic and Statistical Manual for Mental Disorders, 5th Edition

Duke University Religion Index

modified Experiences in Close Relationships scale

ENRICH Marital Satisfaction Scale (ENRICH)

Edmonton Symptom Assessment System-Revised (including constipation and sleep disturbances)

Functional Assessment of Chronic Illness Therapy-Spiritual Well-Being scale

Functional Assessment of Chronic Illness Therapy-Spiritual Well-Being-Non-Illness version

Modified FAMCARE Scale for Patients

Karnofsky Performance Status index

Medical Assistance in Dying

Mixed Linear Models

modified Medical Outcomes Study - Social Support Survey

Patient-Centered Communication-Cancer-6 items

Posttraumatic Stress Disorder Checklist for DSM-5

Patient Health Questionnaire-9

Princess Margaret Cancer Centre

Quality of Dying and Death questionnaire

Quality of Life at the End of Life – Cancer scale

Schedule of Attitudes towards Hastened Death-Abbreviated

short Orientation-Memory-Concentration Test

Self-Perceived Burden Scale

Texas Revised Inventory of Grief – Part II

University Health Network

Wish to Hasten Death

Will to Live Scale.

Carter v. Canada (Attorney General). Supreme Court Judgments 2015 SCC5. [Available from: https://scc-csc.lexum.com/scc-csc/scc-csc/en/item/14637/index.do . Accessed 16 July 2021.

Statutes of Canada. Chapter 3. An Act to amend the Criminal Code and to make related amendments to other Acts (medical assistance in dying) Canada2016. [Available from: https://laws-lois.justice.gc.ca/eng/annualstatutes/2016_3/fulltext.html . Accessed 16 July 2021.

Bill C-7: An Act to amend the Criminal Code (medical assistance in dying). 2020. [Available from: https://www.justice.gc.ca/eng/csj-sjc/pl/charter-charte/c7.html ]. Accessed 16 July 2021.

Health Canada. Second Annual Report on Medical Assistance in Dying in Canada: 2020. Ottawa, ON; June 2021. [Available from: https://www.canada.ca/content/dam/hc-sc/documents/services/medical-assistance-dying/annual-report-2020/annual-report-2020-eng.pdf ]. Accessed 16 July 2021.

Health Canada. Fourth interim report on medical assistance in dying in Canada. In: Health Canada, editor. Ottawa: Health Canada; 2019. p. 1–12.

Rodin G, Shapiro GK, Wales J, Li M. Assisted dying in Canada: lessons from the first 3 years. In: Board RE, Bennet MI, Lewis P, Wagstaff J, Selby P, editors. End of life choices for cancer patients an international perspective. Oxford: EBN Health; 2020. p. 41–9.

Google Scholar

Canadian Cancer Society. Snapshot of incidence, mortality aand survival estimates by cancer type. Toronto: Canadian Cancer Society; 2020. [Available from: https://www.cancer.ca/~/media/cancer.ca/CW/cancer%20information/cancer%20101/Canadian%20cancer%20statistics%20supplementary%20information/2020/2020_cancer-specific-stats.pdf?la=en ]. Accessed 16 July 2021.

Rodin G, Zimmermann C, Rydall A, Jones J, Shepherd FA, Moore M, et al. The desire for hastened death in patients with metastatic cancer. J Pain Symptom Manag. 2007;33(6):661–75. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2006.09.034 .

Monforte-Royo C, Villavicencio-Chávez C, Tomás-Sábado J, Balaguer A. The wish to hasten death: a review of clinical studies. Psychooncology. 2011;20(8):795–804. https://doi.org/10.1002/pon.1839 .

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Balaguer A, Monforte-Royo C, Porta-Sales J, Alonso-Babarro A, Altisent R, Aradilla-Herrero A, et al. An international consensus definition of the wish to hasten death and its related factors. PLoS One. 2016;11(1):e0146184. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0146184 .

Latha KS, Bhat SM. Suicidal behaviour among terminally ill cancer patients in India. Indian J Psychiatry. 2005;47(2):79–83. https://doi.org/10.4103/0019-5545.55950 .

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Nissim R, Gagliese L, Rodin G. The desire for hastened death in individuals with advanced cancer: a longitudinal qualitative study. Soc Sci Med. 2009;69(2):165–71. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2009.04.021 .

Wilson KG, Dalgleish TL, Chochinov HM, Chary S, Gagnon PR, Macmillan K, et al. Mental disorders and the desire for death in patients receiving palliative care for cancer. BMJ Support Palliat Care. 2016;6(2):170–7. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjspcare-2013-000604 .

Chochinov H, Wilson K, Enns M, Mowchun N, Lander S, Levitt M, et al. Desire for death in the terminally ill. Am J Psychiatry. 1995;152(8):1185–91. https://doi.org/10.1176/ajp.152.8.1185 .

Mystakidou K, Parpa E, Katsouda E, Galanos A, Vlahos L. The role of physical and psychological symptoms in desire for death: a study of terminally. Psychooncology. 2006;15(4):355–60. https://doi.org/10.1002/pon.972 .

Chochinov HM, Hack T, Hassard T, Kristjanson LJ, McClement S, Harlos M. Dignity in the terminally ill: a cross-sectional, cohort study. Lancet. 2002;360(9350):2026–30. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(02)12022-8 .

Kremeike K, Galushko M, Frerich G, Romotzky V, Hamacher S, Rodin G, et al. The DEsire to DIe in palliative care: optimization of management (DEDIPOM) - a study protocol. BMC Palliat Care. 2018;17(1):30. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12904-018-0279-3 .

Freeman S, Smith TF, Neufeld E, Fisher K, Ebihara S. The wish to die among palliative home care clients in Ontario, Canada: a cross-sectional study. BMC Palliat Care. 2016;15:24.

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Güell E, Ramos A, Zertuche T, Pascual A. Verbalized desire for death or euthanasia in advanced cancer patients receiving palliative care. Palliat Support Care. 2015;13(2):295–303. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1478951514000121 .

Hendry M, Pasterfield D, Lewis R, Carter B, Hodgson D, Wilkinson C. Why do we want the right to die? A systematic review of the international literature on the views of patients, carers and the public on assisted dying. Palliat Med. 2013;27(1):13–26. https://doi.org/10.1177/0269216312463623 .

Pacheco J, Hershberger PJ, Markert RJ, Kumar G. A longitudinal study of attitudes toward physician-assisted suicide and euthanasia among patients with noncurable malignancy. Am J Hosp Palliat Care. 2003;20(2):99–104. https://doi.org/10.1177/104990910302000207 .

Levene I, Parker M. Prevalence of depression in granted and refused requests for euthanasia and assisted suicide: a systematic review. J Med Ethics. 2011;37(4):205–11. https://doi.org/10.1136/jme.2010.039057 .

Hudson PL, Kristjanson LJ, Ashby M, Kelly B, Schofield P, Hudson R, et al. Desire for hastened death in patients with advanced disease and the evidence base of clinical guidelines: a systematic review. Palliat Med. 2006;20(7):693–701. https://doi.org/10.1177/0269216306071799 .

Johansen S, Hølen JC, Kaasa S, Loge JH, Materstvedt LJ. Attitudes towards, and wishes for, euthanasia in advanced cancer patients at a palliative medicine unit. Palliat Med. 2005;19(6):454–60. https://doi.org/10.1191/0269216305pm1048oa .

Rosenfeld B, Pessin H, Marziliano A, Jacobson C, Sorger B, Abbey J, et al. Does desire for hastened death change in terminally ill cancer patients? Soc Sci Med. 2014;111:35–40. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2014.03.027 .

Emanuel EJ, Fairclough DL, Emanuel LL. Attitudes and desires related to euthanasia and physician-assisted suicide among terminally ill patients and their caregivers. JAMA. 2000;284(19):2460–8. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.284.19.2460 .

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Ohnsorge K, Gudat H, Rehmann-Sutter C. What a wish to die can mean: reasons, meanings and functions of wishes to die, reported from 30 qualitative case studies of terminally ill cancer patients in palliative care. BMC Palliat Care. 2014;13(1):38. https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-684X-13-38 .

Monforte-Royo C, Villavicencio-Chávez C, Tomás-Sábado J, Mahtani-Chugani V, Balaguer A. What lies behind the wish to hasten death? A systematic review and meta-ethnography from the perspective of patients. PLoS One. 2012;7(5):e37117. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0037117 .

Filiberti A, Ripamonti C, Totis A, Ventafridda V, De Conno F, Contiero P, et al. Characteristics of terminal cancer patients who committed suicide during a home palliative care program. J Pain Symptom Manag. 2001;22(1):544–53. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0885-3924(01)00295-0 .

Article CAS Google Scholar

Smith KA, Harvath TA, Goy ER, Ganzini L. Predictors of pursuit of physician-assisted death. J Pain Symptom Manag. 2015;49(3):555–61. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2014.06.010 .

Article Google Scholar

Rosenfeld B, Breitbart W, Stein K, Funesti-Esch J, Kaim M, Krivo S, et al. Measuring desire for death among patients with HIV/AIDS: the schedule of attitudes toward hastened death. Am J Psychiatry. 1999;156(1):94–100. https://doi.org/10.1176/ajp.156.1.94 .

Rodin G, Lo C, Mikulincer M, Donner A, Gagliese L, Zimmermann C. Pathways to distress: the multiple determinants of depression, hopelessness, and the desire for hastened death in metastatic cancer patients. Soc Sci Med. 2009;68(3):562–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2008.10.037 .

Rodin G, Lo C, Rydall A, Shnall J, Malfitano C, Chiu A, et al. Managing Cancer and living meaningfully (CALM): a randomized controlled trial of a psychological intervention for patients with advanced cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2018;36(23):2422–32. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2017.77.1097 .

Tan A, Zimmermann C, Rodin G. Interpersonal processes in palliative care: an attachment perspective on the patient-clinician relationship. Palliat Med. 2005;19(2):143–50. https://doi.org/10.1191/0269216305pm994oa .

Lo C, Lin J, Gagliese L, Zimmermann C, Mikulincer M, Rodin G. Age and depression in patients with metastatic cancer: the protective effects of attachment security and spiritual well-being. Ageing Soc. 2010;30(2):325–36. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0144686X09990201 .

Hillen MA, de Haes HC, Stalpers LJ, Klinkenbijl JH, Eddes EH, Verdam MG, et al. How attachment style and locus of control influence patients' trust in their oncologist. J Psychosom Res. 2014;76(3):221–6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychores.2013.11.014 .

Oldham RL, Dobscha SK, Goy ER, Ganzini L. Attachment styles of Oregonians who request physician-assisted death. Palliat Support Care. 2011;9(2):123–8. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1478951510000660 .

Emanuel EJ, Onwuteaka-Philipsen BD, Urwin JW, Cohen J. Attitudes and practices of euthanasia and physician-assisted suicide in the United States, Canada, and Europe. JAMA. 2016;316(1):79–90. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2016.8499 .

Blanke C, LeBlanc M, Hershman D, Ellis L, Meyskens F. Characterizing 18 years of the death with dignity act in Oregon. JAMA Oncol. 2017;3(10):1403–6. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamaoncol.2017.0243 .

Danyliv A, O’Neill C. Attitudes towards legalising physician provided euthanasia in Britain: the role of religion over time. Soc Sci Med. 2015;128:52–6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2014.12.030 .

Moulton BE, Hill TD, Burdette A. Religion and trends in euthanasia attitudes among U.S. adults, 1977–2004. Sociol Forum. 2006;21(2):249–72. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11206-006-9015-5 .

Li M, Watt S, Escaf M, Gardam M, Heesters A, O'Leary G, et al. Medical assistance in dying - implementing a hospital-based program in Canada. N Engl J Med. 2017;376(21):2082–8. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMms1700606 .

Downar J, Fowler RA, Halko R, Huyer LD, Hill AD, Gibson JL. Early experience with medical assistance in dying in Ontario, Canada: a cohort study. CMAJ. 2020;192(8):E173–E81. https://doi.org/10.1503/cmaj.200016 .

Gamondi C, Fusi-Schmidhauser T, Oriani A, Payne S, Preston N. Family members' experiences of assisted dying: a systematic literature review with thematic synthesis. Palliat Med. 2019;33(8):1091–105. https://doi.org/10.1177/0269216319857630 .

Hales BM, Bean S, Isenberg-Grzeda E, Ford B, Selby D. Improving the medical assistance in dying (MAID) process: a qualitative study of family caregiver perspectives. Palliat Support Care. 2019;17(5):590–5. https://doi.org/10.1017/S147895151900004X .

Braun M, Mikulincer M, Rydall A, Walsh A, Rodin G. The hidden morbidity in cancer: spouse caregivers. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25(30):4829–34. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2006.10.0909 .

Girgis A, Lambert SD, McElduff P, Bonevski B, Lecathelinais C, Boyes A, et al. Some things change, some things stay the same: a longitudinal analysis of cancer caregivers' unmet supportive care needs. Psychooncology. 2013;22(7):1557–64. https://doi.org/10.1002/pon.3166 .

Sklenarova H, Krümpelmann A, Haun MW, Friederich HC, Huber J, Thomas M, et al. When do we need to care about the caregiver? Supportive care needs, anxiety, and depression among informal caregivers of patients with cancer and cancer survivors. Cancer. 2015;121(9):1513–9. https://doi.org/10.1002/cncr.29223 .

Wang T, Molassiotis A, Chung BP, Tan JY. Unmet care needs of advanced cancer patients and their informal caregivers: a systematic review. BMC Palliat Care. 2018;17(1):96. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12904-018-0346-9 .

Goldberg R, Nissim R, An E, Hales S. Impact of medical assistance in dying (MAiD) on family caregivers. BMJ Support Palliat Care. 2021;11(1):107-14. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjspcare-2018-001686 .

Norman G, Streiner D. Biostatistics: The bare essentials. 3rd Edition. Shelton, Connecticut: People's Medical Publishing House; 2008.

Katzman R, Brown T, Fuld P, Peck A, Schechter R, Schimmel H. Validation of a short orientation-memory-concentration test of cognitive impairment. Am J Psychiatry. 1983;140(6):734–9. https://doi.org/10.1176/ajp.140.6.734 .

Karnofsky DA, Burchenal JH. The clinical evaluation of chemotherapeutic agents in cancer. In: MacLeod CM, editor. Evaluation of chemotherapeutic agents. New York: Columbia University Press; 1949. p. 191–205.

Schag CC, Heinrich RL, Ganz PA. Karnofsky performance status revisited: reliability, validity, and guidelines. J Clin Oncol. 1984;2(3):187–93. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.1984.2.3.187 .

Lo C, Burman D, Swami N, Gagliese L, Rodin G, Zimmermann C. Validation of the QUAL-EC for assessing quality of life in patients with advanced cancer. Eur J Cancer. 2011;47(4):554–60. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejca.2010.10.027 .

Grünke B, Philipp R, Vehling S, Scheffold K, Härter M, Oechsle K. Ea. measuring the psychosocial dimensions of quality of life in patients with advanced cancer: psychometrics of the German quality of life at the end of life-Cancer-psychosocial questionnaire. J Pain Symptom Manag. 2018;55(3):985–91. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2017.11.006 .

Carmel S. The will-to-live scale: development, validation, and significance for elderly people. Aging Ment Health. 2017;21(3):289–96. https://doi.org/10.1080/13607863.2015.1081149 .

Kolva E, Rosenfeld B, Liu Y, Pessin H, Breitbart W. Using item response theory (IRT) to reduce patient burden when assessing desire for hastened death. Psychol Assess. 2017;29(3):349–53. https://doi.org/10.1037/pas0000343 .

Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB. The PHQ-9: validity of a brief depression severity measure. J Gen Intern Med. 2001;16(9):606–13. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1525-1497.2001.016009606.x .

Watanabe SM, Nekolaichuk C, Beaumont C, Johnson L, Myers J, Strasser F. A multi-Centre comparison of two numerical versions of the Edmonton symptom assessment system in palliative care patients. J Pain Symptom Manag. 2011;41(2):456–68. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2010.04.020 .

Hannon B, Dyck M, Pope A, Swami N, Banerjee S, Mak E, et al. Modified Edmonton symptom assessment system including constipation and sleep: validation in outpatients with cancer. J Pain Symptom Manag. 2015;49(5):945–52. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2014.10.013 .

Hui D, Bruera E. The Edmonton symptom assessment system 25 years later: past, present and future developments. J Pain Symptom Manag. 2017;53(3):630–43. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2016.10.370 .

Lo C, Burman D, Rodin G, Zimmerman C. Measuring patient satisfaction in oncology palliative care: psychometric properties of the FAMCARE-patient scale. Qual Life Res. 2009;18(6):747–52. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-009-9494-y .

Rosenberg M. Society and the adolescent self-image. Middletown: Wesleyan University Press; 1989.

Lo C, Hales S, Zimmermann C, Gagliese L, Rydall A, Rodin G. Measuring death-related anxiety in advanced cancer: preliminary psychometrics of the death and dying distress scale. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 2011;33(Supplement 2):S140–5. https://doi.org/10.1097/MPH.0b013e318230e1fd .

Krause S, Rydall A, Hales S, Rodin G, Lo C. Initial validation of the death and dying distress scale for the assessment of death anxiety in patients with advanced cancer. J Pain Symptom Manag. 2015;49(1):126–34. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2014.04.012 .

Shapiro GK, Mah K, Li M, Zimmerman C, Hales S, Rodin G. Validation of the Death and Dying Distress Scale in Patients with Advanced Cancer Psychooncology. 2020.

Reeve BB, Thissen DM, Bann CM, Mack N, Treiman K, Sanoff HK, et al. Psychometric evaluation and design of patient-centered communication measures for cancer care settings. Patient Educ Couns. 2017;100(7):1322–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pec.2017.02.011 .

Kristjanson L. Validation and reliability testing of the FAMCARE scale: measuring family satisfaction with advanced cancer care. Soc Sci Med. 1993;36(5):693–701. https://doi.org/10.1016/0277-9536(93)90066-D .

Robinson S, Kissane DW, Brooker J, Hempton C, Michael N, Fischer J, et al. Refinement and revalidation of the demoralization scale: the DS-II - external validity. Cancer. 2016;122(14):2260–7. https://doi.org/10.1002/cncr.30012 .

Simmons LA. Self-perceived burden in cancer patients: validation of the self-perceived burden scale. Cancer Nurs. 2007;30(5):405–11. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.NCC.0000290816.37442.af .

Cella DF, Tulsky DS, Gray G, Sarafian B, Linn E, Bonomi A, et al. The functional assessment of Cancer therapy scale: development and validation of the general measure. J Clin Oncol. 1993;11(3):570–9. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.1993.11.3.570 .

Salsman JM, Garcia SF, Yanez B, Sanford SD, Snyder MA, Victorson D. Physical, emotional, and social health differences between posttreatment young adults with cancer and matched healthy controls. Cancer. 2014;120(15):2247–54. https://doi.org/10.1002/cncr.28739 . Accessed 16 July 2021.

Fowers BJ, Olson DH. ENRICH marital satisfaction scale: a brief research and clinical tool. J Fam Psychol. 1993;7(2):176–85. https://doi.org/10.1037/0893-3200.7.2.176 .

Sherbourne CD, Stewart AL. The MOS social support survey. Soc Sci Med. 1991;32(6):705–14. https://doi.org/10.1016/0277-9536(91)90150-B .

Moser A, Stuck AE, Silliman RA, Ganz PA, Clough-Gorr KM. The eight-item modified medical outcomes study social support survey: psychometric evaluation showed excellent performance. J Clin Epidemiol. 2012;65(10):1107–16. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinepi.2012.04.007 .

Koenig HG, Büssing A. The Duke University religion index (DUREL): a five-item measure for use in epidemiological studies. Religions. 2010;1(1):78–85. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel1010078 .

Kunce LJ, Shaver PR. An attachment-theoretical approach to caregiving in romantic relationships. In: Bartholomew K, Perlman D, editors. Attachment processes in adulthood, vol 5. Advances in personal relationships. London: Jessica Kingsley Publishers; 1994. p. 205–37.

Robinson S, Kissane DW, Brooker J, Michael N, Fischer J, Franco M, et al. Refinement and revalidation of the demoralization scale: the DS-II - internal validty. Cancer. 2016;122(14):2251–9. https://doi.org/10.1002/cncr.30015 .

Given CW, Given B, Stommel M, Collins C, King S, Franklin S. The caregiver reaction assessment (CRA) for caregivers to persons with chronic physical and mental impairments. Res Nurs Health. 1992;15(4):271–83. https://doi.org/10.1002/nur.4770150406 .

Li M, Macedo A, Crawford S, Bagha S, Leung YW, Zimmermann C, et al. Easier said than done: keys to successful implementation of the distress assessment and response tool (DART) program. J Oncol Pract. 2016;12(5):e513–26. https://doi.org/10.1200/JOP.2015.010066 .

McHorney CA, Ware JE Jr, Raczek AE. The MOS 36-item short-form health survey (SF-36): II. Psychometric and clinical tests of validity in measuring physical and mental health constructs. Med Care. 1993;31(3):247–63. https://doi.org/10.1097/00005650-199303000-00006 .

Faschingbaur T, Zisook S, DeVaul R. The Texas revised inventory of grief. In: Zisook S, editor. Biopsychosocial aspects of bereavement. Washington: American Psychiatric Press, Inc.; 1987. p. 109–24.

Ringdal GI, Jordhoy MS, Ringdal K, Kaasa S. Factors affecting grief reactions in close family members to individuals who have died of cancer. J Pain Symptom Manag. 2001;22(6):1016–26. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0885-3924(01)00363-3 .

Blevins CA, Weathers FW, Davis MT, Witte TK, Domino JL. The posttraumatic stress disorder checklist for DSM-5 (PCL-5): development and initial psychometric evaluation. J Trauma Stress. 2015;28(6):489–98. https://doi.org/10.1002/jts.22059 .

Bovin MJ, Marx BP, Weathers FW, Gallagher MW, Rodriguez P, Schnurr PP, et al. Psychometric properties of the PTSD checklist for diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders-fifth edition (PCL- 5) in veterans. Psychol Assess. 2016;28(11):1379–91. https://doi.org/10.1037/pas0000254 .

Patrick DL, Engelberg RA, Curtis JR. Evaluating the quality of dying and death. J Pain Symptom Manag. 2001;22(3):717–26. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0885-3924(01)00333-5 .

Hales S, Zimmermann C, Rodin G. The quality of dying and death: a systematic review of measures. Palliat Med. 2010;24(2):127–44. https://doi.org/10.1177/0269216309351783 .

Lo C, Walsh A, Mikulincer M, Gagliese L, Zimmermann C, Rodin G. Measuring attachment security in patients with advanced cancer: psychometric properties of a modified and brief experiences in close relationships scale. Psychooncology. 2009;18(5):490–9. https://doi.org/10.1002/pon.1417 .

Strauss A, Corbin J. Basics of qualitative research. London: Sage; 1990.

Patton M. Qualitative evaluation and research methods. Newbury Park: Sage; 1990.

Lo C, Zimmermann C, Rydall A, Walsh A, Jones JM, Moore MJ, et al. Longitudinal study of depressive symptoms in patients with metastatic gastrointestinal and lung cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28(18):3084–9. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2009.26.9712 .

Verbeke G, Molenberghs G. Linear mixed models for longitudinal data. New York: Springer; 2000.

Rennie D, Nissim R. The grounded theory method and humanistic psychology. In: Schneider K, Pierson J, Bugental J, editors. The handbook of humanistic psychology: leading edges in theory, practice, and research. 2nd ed. Thousand Oaks: Sage; 2015. p. 297–308.

Download references

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Cassandra Graham for her input on the grant submission.

This study is funded by a competitive, peer-reviewed project grant awarded to ML and GR, co-principal investigators, from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research, Canada’s federal funding agency for health research (Grant No: CIHR PJT 401506; https://cihr-irsc.gc.ca ). An earlier version of our manuscript protocol underwent peer review by the funding body. GKS is supported by the Edith Kirchmann Postdoctoral Fellowship at PM, and by a CIHR 2019 Fellowship Award (CIHR MFE 171271). The funders of the study played no role in the study design, data collection, data analysis, data interpretation, or writing of this report.

Author information

Madeline Li and Gilla K. Shapiro are co-first authors.

Authors and Affiliations

Department of Supportive Care, Princess Margaret Cancer Centre, University Health Network, 620 University Avenue, 12th Floor, Toronto, Ontario, M5G 2C1, Canada

Madeline Li, Gilla K. Shapiro, Roberta Klein, Anne Barbeau, Anne Rydall, Jennifer A. H. Bell, Rinat Nissim, Sarah Hales, Camilla Zimmermann, Rebecca K. S. Wong & Gary Rodin

Department of Psychiatry, Faculty of Medicine, University of Toronto, Toronto, Ontario, Canada

Madeline Li, Jennifer A. H. Bell, Rinat Nissim, Sarah Hales, Camilla Zimmermann & Gary Rodin

Global Institute of Psychosocial, Palliative and End-of-Life Care (GIPPEC), University of Toronto and Princess Margaret Cancer Centre, Toronto, Ontario, Canada

Gilla K. Shapiro, Sarah Hales, Camilla Zimmermann & Gary Rodin

Joint Centre for Bioethics, University of Toronto, Toronto, Ontario, Canada

Jennifer A. H. Bell

Department of Medicine, University of Toronto, Toronto, Ontario, Canada

Camilla Zimmermann

Department of Radiation Oncology, University of Toronto, Toronto, Ontario, Canada

Rebecca K. S. Wong

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

ML and GKS are co-first authors of this work. ML, GKS, AB, RK, AR, and GR made substantial contributions to the study design and writing of the manuscript. ML, GKS, RK, AB, AR, JAHB, RN, SH, CZ, RKSW and GR substantively revised the manuscript, read and approved the final submitted version, and guarantee the integrity of this work.

Corresponding authors

Correspondence to Madeline Li or Gilla K. Shapiro .

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate.

This study was approved on September 2, 2020 by the University Health Network Research Ethics Board (UHN REB #18–6182). All participants will provide written informed consent. Data collection is expected to begin by January 2021.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ . The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver ( http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/ ) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Li, M., Shapiro, G.K., Klein, R. et al. Medical Assistance in Dying in patients with advanced cancer and their caregivers: a mixed methods longitudinal study protocol. BMC Palliat Care 20 , 117 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12904-021-00793-4

Download citation

Received : 26 November 2020

Accepted : 09 June 2021

Published : 21 July 2021

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1186/s12904-021-00793-4

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Desire for hastened death

- Medical assistance in dying

- Medical communication

- Palliative care

- Assisted dying

- Will to live

BMC Palliative Care

ISSN: 1472-684X

- Submission enquiries: [email protected]

- General enquiries: [email protected]

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

- My Bibliography

- Collections

- Citation manager

Save citation to file

Email citation, add to collections.

- Create a new collection

- Add to an existing collection

Add to My Bibliography

Your saved search, create a file for external citation management software, your rss feed.

- Search in PubMed

- Search in NLM Catalog

- Add to Search

Medical Assistance in Dying: Patients', Families', and Health Care Providers' Perspectives on Access and Care Delivery

Affiliations.

- 1 Health Sciences Graduate Program, College of Medicine, University of Saskatchewan, Saskatoon, Saskatchewan, Canada.

- 2 Faculty of Nursing, University of Regina, Regina, Saskatchewan, Canada.

- 3 Department of Respirology, Critical Care, and Sleep Medicine, University of Saskatchewan, Saskatoon, Saskatchewan, Canada.

- 4 College of Medicine, University of Saskatchewan, Saskatoon, Saskatchewan, Canada.

- 5 Department of Community Health and Epidemiology, University of Saskatchewan, Saskatoon, Saskatchewan, Canada.

- 6 Department of Psychiatry, University of Saskatchewan, Saskatoon, Saskatchewan, Canada.

- 7 Department of Anesthesiology, Perioperative Medicine and Pain Management, University of Saskatchewan, Saskatoon, Saskatchewan, Canada.

- 8 Provincial MAID Program, Saskatoon, Saskatchewan, Canada.

- PMID: 32302505

- DOI: 10.1089/jpm.2019.0509

Background: Medical assistance in dying (MAID) became legal in Canada in 2016. Although the legislation is federal, each province is responsible for establishing quality care. Objective: To explore patient, family, and health care provider (HCP) perspectives on MAID access and care delivery and improve regional MAID care delivery. Design: Qualitative exploratory. Setting/Subjects: We interviewed 5 patients (4 met the legislated MAID criteria and 1 did not), 11 family members (4 spouses, 5 children, 1 sibling, and 1 friend), and 14 HCP (3 physicians, 4 social workers, and 7 nurses) from June to August 2017. Measurement: Semistructured interviews, content analysis, and thematic summary. Results: Patients, families, and HCPs highlighted access and delivery concerns regarding program sustainability, care pathway ambiguity, lack of support for care choices, institutional conscientious objection (CO), navigating care in institutions with a CO, and postdeath documentation. Patients and families expressed additional concerns regarding lack of ability to provide advanced MAID consent, and the requirement of independent witnesses on MAID request forms and consent immediately before MAID administration. HCPs were additionally uncertain about professional roles and responsibilities. Ten recommendations to improve regional MAID care and the resultant practice change are presented. Conclusion: Quality improvement (QI) processes are essential to devise an accessible dignified patient- and family-centered MAID program. Ensuring patient and family perspectives are integrated into QI initiatives will assist programs in ensuring the needs of all are considered in structuring and staffing a program that is accessible, easy to navigate, and provides dignified end-of-life care in supportive and respectful work environments.

Keywords: access, quality improvement; medical assistance in dying; patient centered care; physician aid in dying.

PubMed Disclaimer

Similar articles

- Health care providers' ethical perspectives on waiver of final consent for Medical Assistance in Dying (MAiD): a qualitative study. Variath C, Peter E, Cranley L, Godkin D. Variath C, et al. BMC Med Ethics. 2022 Jan 30;23(1):8. doi: 10.1186/s12910-022-00745-4. BMC Med Ethics. 2022. PMID: 35094703 Free PMC article.

- How We Can Improve the Quality of Care for Patients Requesting Medical Assistance in Dying: A Qualitative Study of Health Care Providers. Oczkowski SJW, Crawshaw D, Austin P, Versluis D, Kalles-Chan G, Kekewich M, Curran D, Miller PQ, Kelly M, Wiebe E, Dees M, Frolic A. Oczkowski SJW, et al. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2021 Mar;61(3):513-521.e8. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2020.08.018. Epub 2020 Aug 21. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2021. PMID: 32835830

- Implementation of Medical Assistance in Dying: A Scoping Review of Health Care Providers' Perspectives. Fujioka JK, Mirza RM, McDonald PL, Klinger CA. Fujioka JK, et al. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2018 Jun;55(6):1564-1576.e9. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2018.02.011. Epub 2018 Feb 23. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2018. PMID: 29477968 Review.

- Access Isn't Enough: Evaluating the Quality of a Hospital Medical Assistance in Dying Program. Frolic A, Swinton M, Oliphant A, Murray L, Miller P. Frolic A, et al. HEC Forum. 2022 Dec;34(4):429-455. doi: 10.1007/s10730-022-09486-8. Epub 2022 Aug 26. HEC Forum. 2022. PMID: 36018528 Free PMC article.

- Professional experiences of formal healthcare providers in the provision of medical assistance in dying (MAiD): A scoping review. Ward V, Freeman S, Callander T, Xiong B. Ward V, et al. Palliat Support Care. 2021 Dec;19(6):744-758. doi: 10.1017/S1478951521000146. Palliat Support Care. 2021. PMID: 33781368 Review.

- Perspectives of Canadian health leaders on the relationship between medical assistance in dying and palliative and end-of-life care services: a qualitative study. Shapiro GK, Tong E, Nissim R, Zimmermann C, Allin S, Gibson JL, Lau SCL, Li M, Rodin G. Shapiro GK, et al. CMAJ. 2024 Feb 25;196(7):E222-E234. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.231241. CMAJ. 2024. PMID: 38408784 Free PMC article.

- A qualitative study of experiences of institutional objection to medical assistance in dying in Canada: ongoing challenges and catalysts for change. Close E, Jeanneret R, Downie J, Willmott L, White BP. Close E, et al. BMC Med Ethics. 2023 Sep 21;24(1):71. doi: 10.1186/s12910-023-00950-9. BMC Med Ethics. 2023. PMID: 37735387 Free PMC article.

- Barriers to connecting with the voluntary assisted dying system in Victoria, Australia: A qualitative mixed method study. White BP, Jeanneret R, Willmott L. White BP, et al. Health Expect. 2023 Dec;26(6):2695-2708. doi: 10.1111/hex.13867. Epub 2023 Sep 11. Health Expect. 2023. PMID: 37694553 Free PMC article.

- Institutional Resistance to Medical Assistance in Dying in Canada: Arguments and Realities Emerging in the Public Domain. Knox M, Wagg A. Knox M, et al. Healthcare (Basel). 2023 Aug 15;11(16):2305. doi: 10.3390/healthcare11162305. Healthcare (Basel). 2023. PMID: 37628502 Free PMC article.

- Canadian family members' experiences with guilt, judgment and secrecy during medical assistance in dying: a qualitative descriptive study. Crumley ET, LeBlanc J, Henderson B, Jackson-Tarlton CS, Leck E. Crumley ET, et al. CMAJ Open. 2023 Aug 22;11(4):E782-E789. doi: 10.9778/cmajo.20220140. Print 2023 Jul-Aug. CMAJ Open. 2023. PMID: 37607750 Free PMC article.

- Search in MeSH

LinkOut - more resources

Full text sources, miscellaneous.

- NCI CPTAC Assay Portal

- Citation Manager

NCBI Literature Resources

MeSH PMC Bookshelf Disclaimer

The PubMed wordmark and PubMed logo are registered trademarks of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS). Unauthorized use of these marks is strictly prohibited.

- Open access

- Published: 24 October 2023

Medical assistance in dying for people living with mental disorders: a qualitative thematic review

- Caroline Favron-Godbout 1 &

- Eric Racine 1

BMC Medical Ethics volume 24 , Article number: 86 ( 2023 ) Cite this article

9056 Accesses

2 Citations

2 Altmetric

Metrics details

Medical assistance in dying (MAiD) sparks debate in several countries, some of which allow or plan to allow MAiD where a mental disorder is the sole underlying medical condition (MAiD-MD). Since MAiD-MD is becoming permissible in a growing number of jurisdictions, there is a need to better understand the moral concerns related to this option. Gaining a better understanding of the moral concerns at stake is a first step towards identifying ways of addressing them so that MAiD-MD can be successfully introduced and implemented, where legislations allow it.

Thus, this article aims (1) to better understand the moral concerns regarding MAiD-MD, and (2) to identify potential solutions to promote stakeholders’ well-being. A qualitative thematic review was undertaken, which used systematic keyword-driven search and thematic analysis of content. Seventy-four publications met the inclusion criteria.

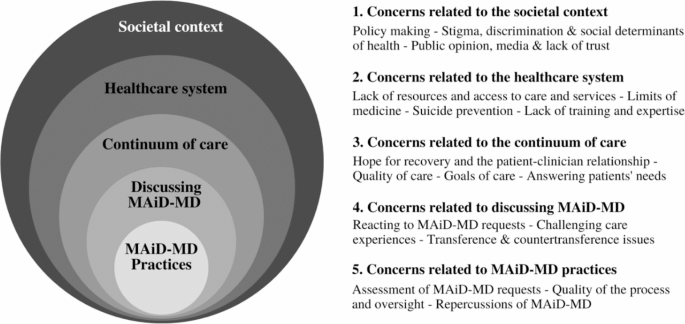

Various moral concerns and proposed solutions were identified and are related to how MAiD-MD is introduced in 5 contexts: (1) Societal context , (2) Healthcare system , (3) Continuum of care , (4) Discussions on the option of MAiD-MD , (5) MAiD-MD practices . We propose this classification of the identified moral concerns because it helps to better understand the various facets of discomfort experienced with MAiD-MD. In so doing, it also directs the various actions to be taken to alleviate these discomforts and promote the well-being of stakeholders.

The assessment of MAiD-MD applications, which is part of the context of MAiD-MD practices, emerges as the most widespread source of concern. Addressing the moral concerns arising in the five contexts identified could help ease concerns regarding the assessment of MAiD-MD.

Peer Review reports

Medical assistance in dying (MAiD), which encompasses euthanasia and physician-assisted suicide [ 1 ], raises debate in several countries. Belgium, The Netherlands, Luxembourg, and Switzerland have allowed people living with mental disorders to access some forms of MAiD for years [ 2 ]. More recently, Spain has passed a MAiD law making people living with mental disorders eligible for MAiD under certain conditions [ 3 ]. Canada has decriminalized MAiD for physical conditions and plans to allow MAiD when a mental disorder is the sole underlying medical condition (MAiD-MD) [ 4 ]. The subject of MAiD-MD is a delicate and controversial one, which has given rise to a great deal of international reflection, leading to the development of a rich literature on the subject. Hence, the literature on MAiD-MD is extensive, and research emerging from countries that allow this practice is complemented by contributions from countries that do not. An important part of the reflections and work carried out on the subject regards the question of whether people living with mental disorders should be eligible for MAiD or not. Literature reviews on the arguments in favor and against MAiD-MD have notably been carried out by Nicolini et al. (2020) and Grassi et al. (2022) [ 5 , 6 ]. The ethical acceptability of MAiD-MD practices is a polarizing issue, which can limit the exploration of nuances in positions and impede the mutual understanding of people with different perspectives on this question. We believe that a promising notion for exploring these nuances is that of moral concerns, as they may provide common ground for discussion between those in favor and those against MAiD-MD. Indeed, moral concerns may be part of the reasons why some people are opposed to MAiD-MD, but also of the drawbacks that those in favor of MAiD-MD feel are important to address if the practice is to be acceptable. For example, moral concerns about the conciliation of MAiD-MD practices and suicide prevention practices may lead some people to oppose MAiD-MD, just as it may qualify the position of those in favor of MAiD-MD (e.g., being in favor on condition that requests for MAiD-MD are not the result of suicidal impulses).

Considering that MAiD-MD is becoming permissible in a growing number of jurisdictions, there is a need to better understand the moral concerns related to this practice. Gaining this understanding is a first step towards identifying ways of addressing them so that MAiD-MD can be successfully introduced and implemented, where legislations allow it. Thus, this article aims (1) to better understand the moral concerns regarding MAiD-MD, and (2) to highlight potential solutions that have been suggested by others to promote stakeholders’ well-being (namely people living with mental disorders, their relatives, and their healthcare professionals). Hence, although highly relevant, moral concerns relating to not allowing MAiD for people with psychiatric suffering are not covered by this literature review.

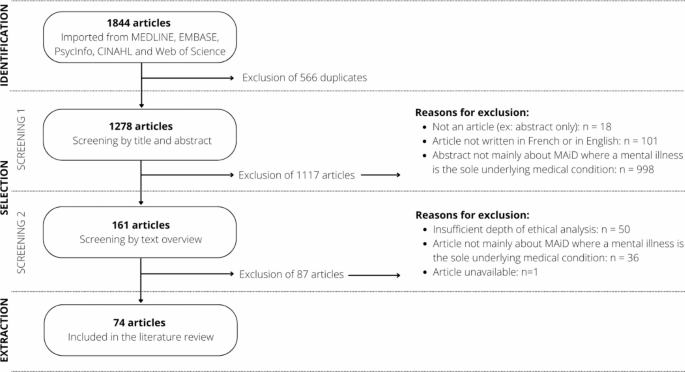

This qualitative thematic review relied on systematic literature searches in addition to screening and structured thematic content extraction strategy, inspired by Arksey & O’Malley (2005) and by Levac & al. (2010), as well as by more structured forms of thematic literature reviews [ 7 , 8 , 9 , 10 , 11 , 12 ]. Figure 1 illustrates the article selection process in the form of a PRISMA-type diagram.

PRISMA diagram illustrating the systematic article selection process

Identifying the research question: The following questions guided the review: What moral concerns are reported regarding medical assistance in dying where a mental disorder is the sole underlying medical condition? What possible solutions are proposed to address these concerns?

Identifying relevant studies: The literature searches were developed around three concepts: moral concerns, medical assistance in dying, and mental disorders. The search strategy was validated by a librarian from Université de Montréal’s School of Public Health and put forward MeSH terms (Medical Subject Headings) and keywords for each concept, which were applied to the title, abstract, and keyword headings fields. Moral concerns were identified using the “ethics” and “morals” MeSH terms, with the equation (Moral* or bioethic* or ethic*); medical assistance in dying was targeted using the MeSH terms “suicide, assisted”, and “euthanasia, active, voluntary”, with the equation ((Assist* or “medical aid”) ADJ2 (dying or dead or death or suicide or die)) or euthanas*; mental disorders were targeted with the “mental disorders” MeSH term, with the equation mental disorder* or mental health or mental illness* or psychiatric disorder* or psychiatric illness* or psychiatric disease* or behavior disorder* or bipolar* or depress* or psychos* or psychot* or schizoaffect* or schizphren* or cyclothym* or anxiety* or obsessive-compulsive disorder* or post-traumatic stress* or dissociat* disorder* or personality disorder* or eating disorder* or social phobia or substance-related disorder*. The literature search was conducted on July 13, 2022, in the MEDLINE (n = 641), EMBASE (n = 509), CINAHL (n = 170), PsycInfo (n = 268) and Web of Science (n = 256) databases, and the identified articles were imported into the Covidence software (N = 1278).