- The University Of Chicago

- Visitors & Fellows

- BFI Employment Opportunities

- Big Data Initiative

- Chicago Experiments Initiative

- Health Economics Initiative

- Industrial Organization Initiative

- International Economics and Economic Geography Initiative

- Macroeconomic Research Initiative

- Political Economics Initiative

- Price Theory Initiative

- Ronzetti Initiative for the Study of Labor Markets

- Becker Friedman Institute China

- Becker Friedman Institute Latin America

- Macro Finance Research Program

- Program in Behavioral Economics Research

- Development Innovation Lab

- Energy Policy Institute at the University of Chicago

- TMW Center for Early Learning + Public Health

- UChicago Scholars

- Visiting Scholars

- Saieh Family Fellows

Rational inattention models characterize optimal decision-making in data-rich environments. In such environments, it can be costly to look carefully at all of the information. Some information is much more salient for the decision at hand and merits closer scrutiny. The...

This paper characterizes the transition dynamics of a continuous-time neoclassical production economy with capital accumulation in which households face idiosyncratic income risk and cannot commit to repay their debt. Therefore, even though a full set of contingent claims that pay...

Interest in market power has recently surged among economists in many fields, well beyond its traditional home in industrial organization. This has focused empirical attention on markups, the ratios of price to marginal cost in product markets, and markdowns, the...

- View All caret-right

Upcoming Events

2024 ai in social science conference, economic theory conference honoring phil reny, 2024 women in empirical microeconomics conference, past events, bfi student lunch series – the impact of incarceration on employment, earnings, and tax filing, macro financial modeling meeting spring 2012, modeling financial sector linkages to the macroeconomy, research briefs.

Interactive Research Briefs

- Media Mentions

- Press Releases

- Search Search

- The Effects of Sexism on American Women: The Role of Norms vs. Discrimination

- Sexism experienced during formative years stays with girls into adulthood

- These background norms can influence choices that women make and affect their life outcomes

- In addition, women face different levels of sexism and discrimination in the states where they live as adults

- Sexism varies across states and can have a significant impact on a woman’s wages and labor market participation, and can also influence her marriage and fertility rates

What type of life experiences will these women have in terms of the work they do and the wages they earn? Will they get married and, if so, how young? If they have children, when will they start to raise a family? How many children will they have? According to the authors of the new BFI working paper, “The Effects of Sexism on American Women: The Role of Norms vs. Discrimination,” the answers to those questions depend crucially on where women are born and where they choose to live their adult lives.

Kerwin Kofi Charles, professor at the Harris School of Public Policy, and his colleagues employ a novel approach that examines how prevailing sexist beliefs shape life outcomes for women. Essentially, they find that sexism affects women through two channels: one is their own preferences that are shaped by where they grow up, and the other is the sexism they experience in the place they choose to live as adults.

On average, not all states are average The average American woman’s socioeconomic outcomes have improved dramatically over the past 50 years. Her wages and probability of employment, relative to the average man’s, have risen steadily over that time. She is also marrying later and bearing children later, as well as having fewer total children. However, these are national averages and these phenomena do not hold in all states across America. Indeed, the gap between men and women that existed in a particular state 50 years ago is largely the same size today. In other words, if a state exhibited less gender discrimination 50 years ago, it retains that narrower gap today; a state that exhibited more discrimination in 1970 has a similarly wide gap today. Much research over the years has focused on broad national trends when measuring sexism and its effect on women’s lives. A primary contribution of this paper is that it documents cross-state differences in women’s outcomes and incorporates non-market factors, like cultural norms. The focus of the authors’ analysis are the four outcomes described above: wages, employment, marriage, and fertility. Of the many forms sexism might take, the authors focus on negative or stereotypical beliefs about whether women should enter the workplace or remain at home. Specifically, sexism prevails in a market when residents believe that:

• women’s capacities are inferior to men;

• families are hurt when women work;

• and men and women should adhere to strict roles in society.

These cultural norms are not only forces that occur to women from external sources, but they are forces that also exist within women, and are strongly affected by where a woman is raised. For example, a girl may grow up within a culture that prizes stay-at-home mothers over working moms, as well as early marriages and large families. These are what the authors describe as background norms, and they are able to estimate the influence of these background norms throughout adulthood by comparing women who were born in one place and moved to different places, and those who were born in different places and moved to the same place. Once a woman reaches adulthood and chooses a place to live, she is then influenced by discrimination in the labor market and by what the authors term residential sexism, or those current norms that they experience in their new hometown. On the question of who engages in sexist behavior, men and/ or women, the authors are clear: men are the purveyors of discrimination in the market (whether women are hired for or promoted to certain jobs), and women determine norms (or residential sexism) that influence such outcomes as marriage and fertility.

The authors conduct a number of rigorous tests based on a broad array of data to reach their conclusions about women’s wages, their labor force participation relative to men, and the ages at which women aged 20-40 married and had their first child. For example, their information on sexism comes from the General Social Survey (GSS), which is a nationally representative survey that asks respondents various questions, among others, about their attitudes or beliefs about women’s place in society.

Sexism affects women through two channels: one is their own preferences that are shaped by where they grow up, and the other is the sexism they experience in the place they choose to live as adults.

The authors reveal how prevailing sexist beliefs about women’s abilities and appropriate roles affect US women’s socioeconomic outcomes. Studying adults who live in one state but who were born in another, they show that sexism in a woman’s state of birth and in her current state of residence both lower her wages and likelihood of labor force participation, and lead her to marry and bear her first child sooner. The sexism a woman experiences where she was raised, or background sexism, affects a woman’s outcomes even after she is an adult living in another place through the influence of norms that she internalized during her formative years. Further, the sexism present where a woman lives (residential sexism) affects her non-labor market outcomes through the influence of prevailing sexist beliefs of other women where she lives. By contrast, residential sexism’s effects on her labor market outcomes seem to operate chiefly through the mechanism of market discrimination by sexist men. Finally, and importantly, the authors find sound evidence that prejudice-based discrimination, undergirded by prevailing sexist beliefs that vary across space, may be an important driver of women’s outcomes in the US.

CLOSING TAKEAWAY By studying adults who were born in one place but live in another, the authors reveal the effects of sexism on women’s outcomes in the market through discrimination (wages and jobs), as well as in non-market settings through cultural norms (marriage and fertility).

- Kerwin Kofi Charles

- Harris Professor Kerwin Charles draws connections between workplace and birthplace among American women

- New economic research from Harris School of Public Policy’s Kerwin Kofi Charles, an affiliated scholar of BFI’s Ronzetti Initiative for the Study of Labor Markets, looks at “How Sexism Follows Women from the Cradle to the Workplace”

- Research from Harris School of Public Policy’s Kerwin Kofi Charles, an affiliated scholar of BFI’s Ronzetti Initiative for the Study of Labor Markets, cited in discussion on the growing wage gap between white and black men

- Share full article

Advertisement

This Is How Everyday Sexism Could Stop You From Getting That Promotion

By Jessica Nordell and Yaryna Serkez Oct. 14, 2021

By Jessica Nordell Graphics by Yaryna Serkez

Jessica Nordell is a science and culture journalist. Yaryna Serkez is a writer and a graphics editor for Opinion.

When the computer scientist and mathematician Lenore Blum announced her resignation from Carnegie Mellon University in 2018, the community was jolted. A distinguished professor, she’d helped found the Association for Women in Mathematics, and made seminal contributions to the field. But she said she found herself steadily marginalized from a center she’d help create — blocked from important decisions, dismissed and ignored. She explained at the time : “Subtle biases and microaggressions pile up, few of which on their own rise to the level of ‘let’s take action,’ but are insidious nonetheless.”

It’s an experience many women can relate to. But how much does everyday sexism at work matter? Most would agree that outright discrimination when it comes to hiring and advancement is a bad thing, but what about the small indignities that women experience day after day? The expectation that they be unfailingly helpful ; the golf rounds and networking opportunities they’re not invited to ; the siphoning off of credit for their work by others; unfair performance reviews that penalize them for the same behavior that’s applauded in men; the “ manterrupting ”?

When I was researching my book “The End of Bias: A Beginning” I wanted to understand the collective impact of these less visible forms of bias, but data were hard to come by. Bias doesn’t happen once or twice; it happens day after day, week after week. To explore the aggregate impact of routine gender bias over time, I teamed up with Kenny Joseph, a computer science professor at the University at Buffalo, and a graduate student there, Yuhao Du, to create a computer simulation of a workplace. We call our simulated workplace “NormCorp.” Here’s how it works.

NormCorp is a simple company. Employees do projects, either alone or in pairs. These succeed or fail, which affects a score we call “promotability.” Twice a year, employees go through performance reviews, and the top scorers at each level are promoted to the next level.

NormCorp employees are affected by the kinds of gender bias that are endemic in the workplace. Women’s successful solo projects are valued slightly less than men’s , and their successful joint projects with men accrue them less credit . They are also penalized slightly more when they fail . Occasional “stretch” projects have outsize rewards, but as in the real world, women’s potential is underrecognized compared with men’s, so they must have a greater record of past successes to be assigned these projects. A fraction of women point out the unfairness and are then penalized for the perception that they are “self-promoting.” And as the proportion of women decreases, those that are left face more stereotyping .

We simulated 10 years of promotion cycles happening at NormCorp based on these rules, and here is how women’s representation changed over time.

Simulation of Normcorp promotions over 10 years, with female performance undervalued by 3 percent

Simulation results over time

These biases have all been demonstrated across various professional fields. One working paper study of over 500,000 physician referrals showed that women surgeons receive fewer referrals after successful outcomes than male surgeons. Women economists are less likely to receive tenure the more they co-author papers with men. An analysis at a large company found that women’s, as well as minority men’s, performance was effectively “discounted” compared with that of white men.

And women are penalized for straying from “feminine” personality traits. An analysis of real-world workplace performance evaluations found that more than three-quarters of women’s critical evaluations contained negative comments about their personalities, compared with 2 percent of men’s. If a woman whose contributions are overlooked speaks up, she may be labeled a self-promoter, and consequently face further obstacles to success . She may also become less motivated and committed to the organization . The American Bar Association found that 70 percent of women lawyers of color considered leaving or had left the legal profession entirely, citing being undervalued at work and facing barriers to advancement.

Our model does not take into account women, such as Lenore Blum, who quit their jobs after experiencing an unmanageable amount of bias. But it visualizes how these penalties add up over time for women who stay, so that by the time you reach more senior levels of management, there are fewer women left to promote. These factors not only prevent women from reaching the top ranks in their company but for those who do, it also makes the career path longer and more demanding.

Small change, big difference

Even a tiny increase in the amount of gender bias could lead to dramatic underrepresentation of women in leadership roles over time..

Women’s performance is valued 3 percent less

Women’s performance is valued 5 percent less

Half as many women at level 7 and

only 2 percent of women at C-suite.

Half as many women at level 7 and only 2 percent of women at C-suite.

Women’s performance is valued 3% less

Women’s performance is valued 5% less

When we dig into the trajectory of individual people in our simulation, stories begin to emerge. With just 3 percent bias, one employee — let’s call her Jenelle — starts in an entry-level position, and makes it to the executive level, but it takes her 17 performance review cycles (eight and a half years) to get there, and she needs 208 successful projects to make it. “William” starts at the same level but he gets to executive level much faster — after only eight performance reviews and half Jenelle’s successes at the time she becomes an executive.

Our model shows how large organizational disparities can emerge from many small, even unintentional biases happening frequently over a long period of time. Laws are often designed to address large events that happen infrequently and can be easily attributed to a single actor—for example, overt sexual harassment by a manager — or “pattern and practice” problems, such as discriminatory policies. But women’s progress is hindered even without one egregious incident, or an official policy that is discriminatory.

Women’s path to success might be longer and more demanding

Career paths for employees that reached level 7 by the end of the simulation..

successful projects

“William”

started at the entry-level and reached level 7 in 4 years.

It took “Jenelle”

8.5 years to get

to the same level.

Entry level

1 year of promotions

started at the entry-

level and reached level 7 in 4 years.

8.5 years to get to the same level.

It took “Jenelle” 8.5 years to get to the same level.

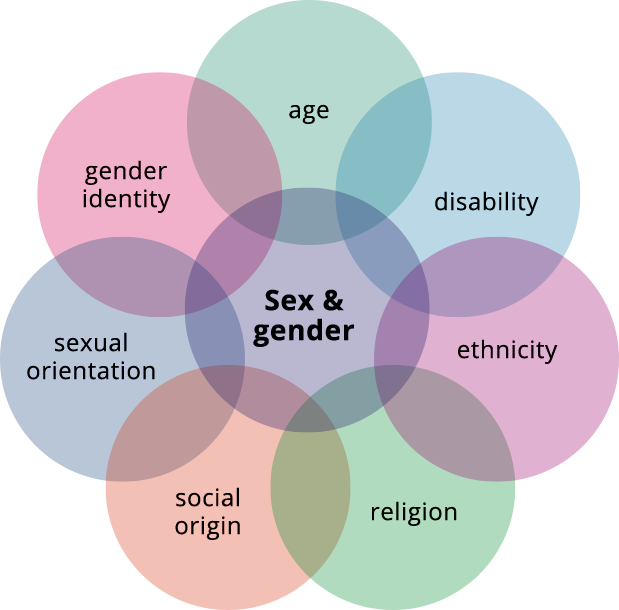

Gender bias takes on different dimensions depending on other intersecting aspects of a person’s identity, such as race, religion, ethnicity, sexual orientation, disability and more. Another American Bar Association study found that white women and men of color face similar hurdles to being seen as competent, but women of color face more than either group.

Backlash, too, plays out differently for women of different racial groups, points out Erika Hall, an Emory University management professor. A survey of hundreds of women scientists she helped conduct found that Asian American women reported the highest amount of backlash for self-promotion and assertive behavior. An experimental study by the social psychologist Robert Livingston and colleagues, meanwhile, found that white women are more penalized for demonstrating dominant behavior than Black women. Our model does not account for the important variations in bias that women of different races experience.

So what’s to be done? Diversity trainings are common in companies, educational institutions and health care settings, but these may not have much effect when it comes to employees’ career advancement. The sociologists Frank Dobbin and Alexandra Kalev found that after mandatory diversity trainings, the likelihood that women and men of color became managers either stayed the same or decreased , possibly because of backlash. Some anti-bias trainings have been shown to change behavior, but any approach needs to be evaluated, as psychologist Betsy Levy Paluck has said, “on the level of rigorous testing of medical interventions.”

We also explored a paradox. Research shows that in many fields, a greater proportion of men correlates with more bias against women . At the same time, in fields or organizations where women make up the majority, men can still experience a “glass escalator,” being fast-tracked to senior leadership roles. School superintendents, who work in the women-dominated field of education but are more likely to be men, are one example. To make sense of this, we conceptualized bias at work as a combination of both organizational biases that can be influenced by organizational makeup and larger societal biases.

What we found was that if societal biases are strong compared with those in the organization, a powerful but brief intervention may have only a short-term impact. In our simulation, we tested this by introducing quotas — requiring that the majority of promotions go to women — in the context of low, moderate, or no societal bias. We made the quotas time-limited, as real world efforts to combat bias often take the form of short-term interventions.

Our quotas changed the number of women at upper levels of the corporate hierarchy in the short term, and in turn decreased the gender biases against women rising through the company ranks. But when societal biases were still a persistent force, disparities eventually returned, and the impact of the intervention was short-lived.

Quotas may not be enough

In the presence of societal biases, the effect of a short-term program of quotas disappears over time..

Societal bias has moderate effect

100% of executives

Quotas are introduced. 70% of all promotions go to women.

Majority of executives are men

YEARS OF PROMOTIONS

Societal bias has no effect

Equal representation

representation

What works? Having managers directly mentor and sponsor women improves their chance to rise. Insisting on fair, transparent and objective criteria for promotions and assignments is essential, so that decisions are not ambiguous and subjective, and goal posts aren’t shifting and unwritten. But the effect of standardizing criteria, too, can be limited, because decision-makers can always override these decisions and choose their favored candidates.

Ultimately, I found in my research for the book, the mindset of leaders plays an enormous role. Interventions make a difference, but only if leaders commit to them. One law firm I profiled achieved 50 percent women equity partners through a series of dramatic moves, from overhauling and standardizing promotion criteria, to active sponsorship of women, to a zero-tolerance policy for biased behavior. In this case, the chief executive understood that bias was blocking the company from capturing all the available talent. Leaders who believe that the elimination of bias is essential to the functioning of the organization are more likely to take the kind of active, aggressive, and long-term steps needed to root out bias wherever it may creep into decision making.

Sexism: Gender, Class and Power Essay

- To find inspiration for your paper and overcome writer’s block

- As a source of information (ensure proper referencing)

- As a template for you assignment

Introduction

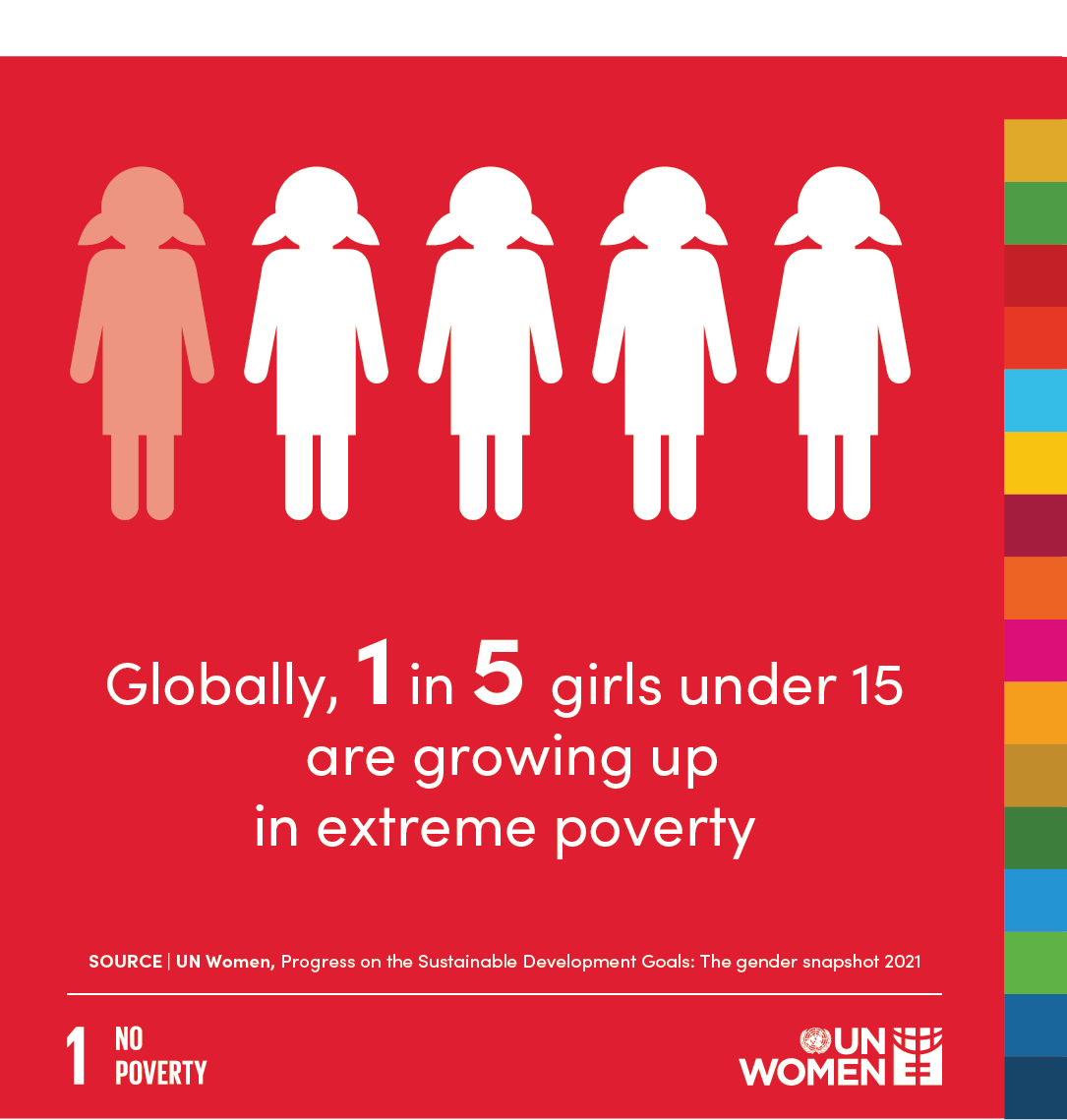

Sexism is one of the challenges that most societies in the contemporary world have struggled to address without any meaningful progress. It refers to discriminatory or abusive behavior towards members of the opposite sex. Although anybody is vulnerable to sexism, it is majorly documented as a problem faced by women and girls. According to psychologists, the challenge of sexism is necessitated by factors such as gender roles and stereotypes across various societies (Dawson, 2018).

Over the years, various human rights groups have made an effort to create awareness about sexism and the probable dangers the victims might be exposed to if effective management strategies are not put in place. Research has established that in societies where sexism is highly rooted, victims are often vulnerable to rape and sexual harassment (Brewington, 2013). Cases of sexism against women are very common in the workplace.

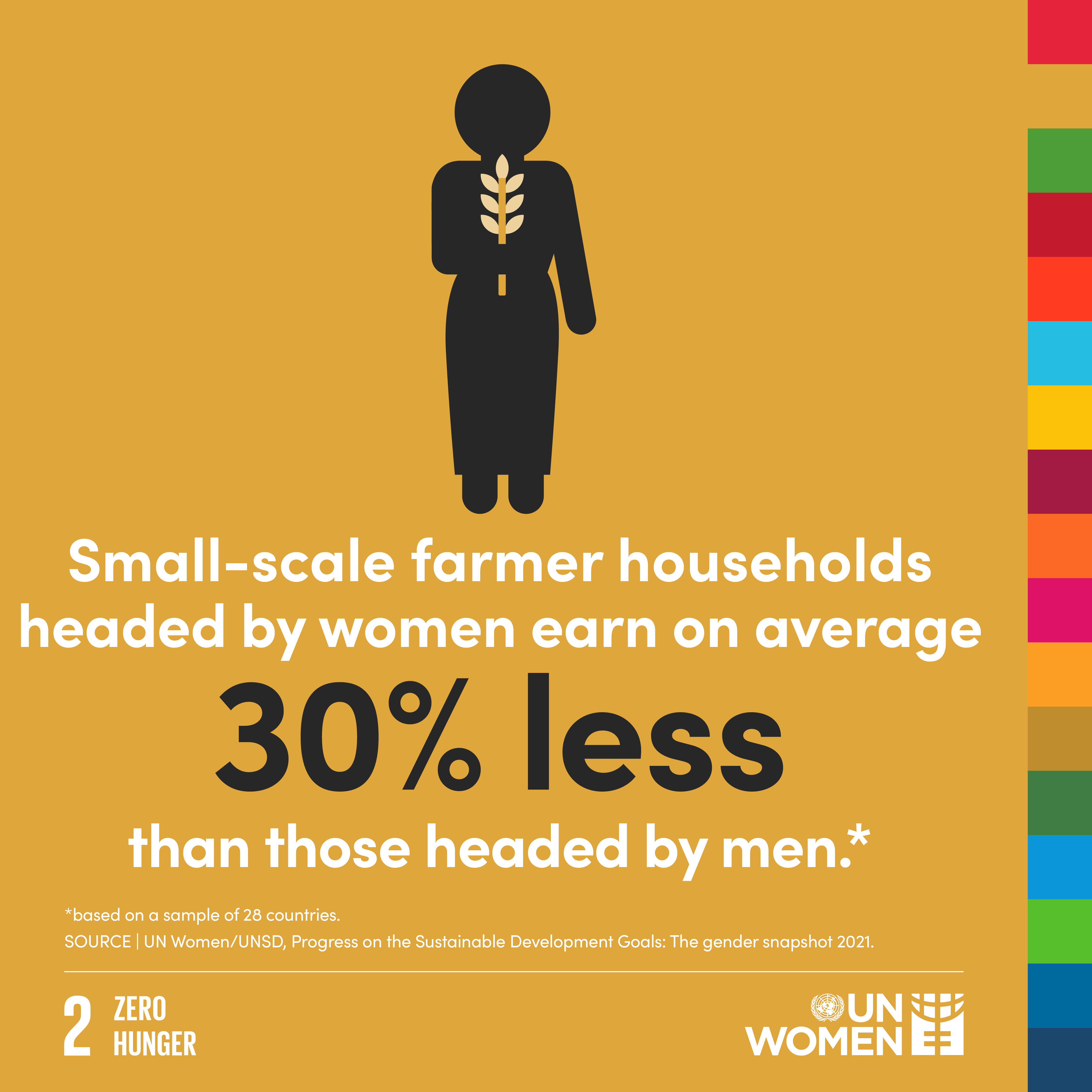

Women are very vulnerable to sexual harassment in the workplace as their male colleagues and bosses often ask for sexual favors in exchange for promotions and salary reviews (Tulshyan, 2016). Women also argue that they are often overlooked in leadership positions because men are considered to have a better chance of succeeding. Sexism is a deep-rooted societal vice that ought to be eliminated in order to promote the value of humanity.

Since the turn of the century, people are more vocal with regard to the danger of sexism. Social networking sites are one of the platforms that people have used to highlight the challenges faced by victims of sexism and offer solutions to the problem. In 2012, the infamous Everyday Sexism project was launched with an aim to expose the numerous acts of sexism across the United Kingdom. The project quickly got the attention of the world as people gave shocking reactions to the degree to which the vice was rampant, especially in the streets (Brewington, 2013).

According to research, social media, as well as print and electronic media, have contributed greatly to the advancement of sexism regardless of the fact that they are also being used to fight the vice. For example, the contemporary hip-hop music industry in the United States has been accused of promoting sexism through their music videos. The genre has led to women being viewed more from a sexual angle because of the way they appear in the music videos.

These videos are aired across major television channels and readily available for consumption by the global audience through YouTube. Fashion magazines have also contributed to the growing challenge of sexism, especially towards women, because the artistic presentation of the female body is angled in a sexual manner (Brewington, 2013).

Apart from the inappropriate portrayal of human bodies by media, sexism is highly prevalent in modern society in several other ways. In the workplace, women often complain of the general assumption that men are more qualified and knowledgeable compared to women (Tulshyan, 2016). It is frustrating for women when a colleague seeks advice or clarification from a male peer when they know that they are in a better position to do the same. Women also consider the inability of an employer to allocate a certain task to them simply because they are physically demanding as an act of sexism (Dawson, 2018).

Women go to the gym and participate in various sports just as men do. Thus, it is wrong to assume they cannot meet the physical demands of a task. Psychologists argue that sexism is a relative concept with regard to the way various societies explain and comprehend it. This is evidenced in the different actions or elements that are considered as being sexist. In some societies, the fact that women are made to change their surname when they get married is considered sexism. Women feel that it is not necessary for them to give up their last name because of a process that even men undergo, yet they get to retain theirs (Brewington, 2013).

Another common form of sexism is sexist language. Studies have established that men are less vulnerable compared to women when it comes to sexual objectification when being addressed. It is important for people to use gender-sensitive language, especially in situations where both men and women are involved. For example, it is wrong to use masculine generics such as “Chairman” when referring to a female leader. Instead, one should use a gender-sensitive term such as chairperson (Lipman, 2018).

It is also an act of sexism to refer to a group of people with both men and women as “Guys” because it creates an impression that women are a category below men as human beings. It is also a common occurrence to hear men referring to adult women as girls. This often infantilizes a woman because it makes one feel like the person addressing her is giving an indication that they are not mature.

The most unfortunate thing about sexist language is the casual manner in which it has been used over the years, to the extent that it has become part of the conventional glossary. This is one of the major challenges facing the fight against sexism. Objectification of women through sexist language is rooted in the stereotypes the society develops from the way girls are raised and theories about their beauty (Evans, 2016). Over the years, women have been used to market products through various forms of advertisements. This has influenced girls to believe that they are as valuable as they look. Therefore, any woman whose beauty fails to meet societal standards tends to feel less valuable.

Sexism has robbed women of their safety, comfort, and voice. Many women who have been a victim of street harassment from men argue that such experiences act as an affirmation that their bodies are owned by the society (Brewington, 2013). Due to laxity within the society, women are made to unwillingly take street harassment as intended compliments rather than abuse. Domestic violence is a form of sexism that has taken away the voice of women.

In many societies, many cases of domestic violence against men and women end up unreported because the victims know they will not get any help with ease. It’s a human rights violation that often demeans the victim because the violator perceives the victim as being weak (Evans, 2016). Unfortunately, domestic violence is legal in places such as the United Arab Emirates, where husbands are allowed to discipline their wives as long as they do not inflict visible injuries.

South Asia is common for practicing a form of sexism called Gendercide. It involves the killing of children of a specific gender. It is close to gender-selective-abortion, where women are forced to terminate their pregnancies depending on the sex of the unborn child. In these practices, girls are targeted more than boys. The same case applies to female genital mutilation, which human rights groups consider as the gravest form of sexism (Evans, 2016).

In contemporary society, technology is widely abused to advance sexist agendas. Women always complain of suffering rape anxiety because people use phone calls and social media posts to deliver threats. No one chooses to be a victim of sexism; thus, avoiding walking in the streets unaccompanied or with people of the same gender is not enough. Cyberbullying is a strategy widely used by sexist people to harass their targets. The internet has turned the world into a global village.

Thus cultural interaction has been greatly heightened (Brewington, 2013). This effect is manifested a lot in the fashion industry, where the dres’ codes for men and women have undergone a huge transformation. Psychologists argue that dres’ codes are sexist in nature. They often limit the power and confidence of women, depending on the societal perception of a certain trend. The style of women wearing pants started in the developed countries as a way of helping women address the threat of rape. Several decades later, it has become a global trend. Some women argue that their lies in wearing dresses, but they are often forced to wear pants for safety purposes (Evans, 2016).

The concept of sexism is very broad and cannot be explained exhaustively. However, it is common knowledge that there is an urgent need to address this global challenge in order to achieve the common good. Gender equality and sensitivity is a right of every human being, thus the need to ensure that we create a more inclusive society. In order to achieve this feat, a change in attitude with regard to the way different genders perceive each other is very important. Men need to understand that they are not biologically programmed to harass women or objectify them.

Brewington, C. (2013). The sacred place of exile: Pioneering women and the need for a new women’s missionary movement . New York, NY: Wipf and Stock Publishers.

Dawson, T. (2018). Gender, class and power: An analysis of pay inequalities in the workplace . New York, NY: Palgrave Macmillan.

Evans, M. (2016). The persistence of gender inequality . New York, NY: John Wiley & Sons.

Lipman, J. (2018). That’s what she said: What men need to know and women need to tell them about working together . New York, NY: Harper Collins.

Tulshyan, R. (2016). The diversity advantage: Fixing gender inequality in the workplace . New York, NY: Create Space Independent Publishing Platform.

- Diversity Organizations and Gender Issues in the US

- Gender Inequality: "Caliban and the Witch" by Federici

- Misogyny and Sexism in Policing

- The Sexism Behind HB16 Bill

- Everyday Sexism in Relation to Everyday Disablism

- Gender Inequality Index 2013 in the Gulf Countries

- Feminist Perspective: “The Gender Pay Gap Explained”

- Transforming the Debate on Sexual Inequality

- Gender Stereotypes: Interview with Dalal Al Rabah

- Women's Work Advantages and Disadvantages Essay

- Chicago (A-D)

- Chicago (N-B)

IvyPanda. (2021, May 7). Sexism: Gender, Class and Power. https://ivypanda.com/essays/sexism-gender-class-and-power/

"Sexism: Gender, Class and Power." IvyPanda , 7 May 2021, ivypanda.com/essays/sexism-gender-class-and-power/.

IvyPanda . (2021) 'Sexism: Gender, Class and Power'. 7 May.

IvyPanda . 2021. "Sexism: Gender, Class and Power." May 7, 2021. https://ivypanda.com/essays/sexism-gender-class-and-power/.

1. IvyPanda . "Sexism: Gender, Class and Power." May 7, 2021. https://ivypanda.com/essays/sexism-gender-class-and-power/.

Bibliography

IvyPanda . "Sexism: Gender, Class and Power." May 7, 2021. https://ivypanda.com/essays/sexism-gender-class-and-power/.

What Is Sexism? Defining a Key Feminist Term

Compassionate Eye Foundation / Monashee Frantz / Getty Images

- History Of Feminism

- Important Figures

- Women's Suffrage

- Women & War

- Laws & Womens Rights

- Feminist Texts

- American History

- African American History

- African History

- Ancient History and Culture

- Asian History

- European History

- Latin American History

- Medieval & Renaissance History

- Military History

- The 20th Century

- J.D., Hofstra University

- B.A., English and Print Journalism, University of Southern California

Sexism means discrimination based on sex or gender, or the belief that because men are superior to women, discrimination is justified. Such a belief can be conscious or unconscious . In sexism, as in racism, the differences between two (or more) groups are viewed as indications that one group is superior or inferior. Sexist discrimination against girls and women is a means of maintaining male domination and power. The oppression or discrimination can be economic, political, social, or cultural.

Elements of Sexism

- Sexism includes attitudes or ideology, including beliefs, theories, and ideas that hold one group (usually male) as deservedly superior to the other (usually female), and that justify oppressing members of the other group on the basis of their sex or gender.

- Sexism involves practices and institutions and the ways in which oppression is carried out. These need not be done with a conscious sexist attitude but may be unconscious cooperation in a system that has been in place already in which one sex (usually female) has less power and fewer goods in the society.

Oppression and Domination

Sexism is a form of oppression and domination. As author Octavia Butler put it:

"Simple peck-order bullying is only the beginning of the kind of hierarchical behavior that can lead to racism, sexism, ethnocentrism, classism, and all the other 'isms' that cause so much suffering in the world."

Some feminists have argued that sexism is the primal, or first, form of oppression in humanity and that other oppressions are built on the foundation of oppression of women. Feminist Andrea Dworkin holds that position, stating:

"Sexism is the foundation on which all tyranny is built. Every social form of hierarchy and abuse is modeled on male-over-female domination."

Feminist Origins of the Word

The word "sexism" became widely known during the women's liberation movement of the 1960s. At that time, feminist theorists explained that the oppression of women was widespread in nearly all human society, and they began to speak of sexism instead of male chauvinism. Whereas male chauvinists were usually individual men who expressed the belief that they were superior to women, sexism referred to collective behavior that reflected society as a whole.

Australian writer Dale Spender noted that she was:

"...old enough to have lived in a world without sexism and sexual harassment. Not because they weren’t everyday occurrences in my life but because THESE WORDS DIDN’T EXIST. It was not until the feminist writers of the 1970s made them up, and used them publicly and defined their meanings—an opportunity that men had enjoyed for centuries—that women could name these experiences of their daily life."

Many women in the feminist movement of the 1960s and 1970s (the so-called second wave of feminism) came to their consciousness of sexism via their work in social justice movements. Social philosopher Bell Hooks argues:

"Individual heterosexual women came to the movement from relationships where men were cruel, unkind, violent, unfaithful. Many of these men were radical thinkers who participated in movements for social justice, speaking out on behalf of the workers, the poor, speaking out on behalf of racial justice. However, when it came to the issue of gender they were as sexist as their conservative cohorts."

How Sexism Works

Systemic sexism, like systemic racism, is the perpetuation of the oppression and discrimination without necessarily any conscious intention. The disparities between men and women are simply taken as givens and are reinforced by practices, rules, policies, and laws that often seem neutral on the surface but in fact disadvantage women.

Sexism interacts with racism, classism, heterosexism, and other oppressions to shape the experience of individuals. This is called intersectionality . Compulsory heterosexuality is the prevailing belief that heterosexuality is the only "normal" relationship between the sexes, which, in a sexist society, benefits men.

Women as Sexists

Women can be conscious or unconscious collaborators in their own oppression if they accept the basic premises of sexism: that men have more power than women because they deserve more power than women. Sexism by women against men would only be possible in a system in which the balance of social, political, cultural, and economic power was measurably in the hands of women, a situation which does not exist today.

Men May Be Oppressed by Sexism

Some feminists have argued that men should be allies in the fight against sexism because men, too, are not whole in a system of enforced male hierarchies. In a patriarchal society , men are themselves in a hierarchical relationship to each other, with more benefits to the males at the top of the power pyramid.

Others have argued that the benefit males derive from sexism—even if that benefit is not consciously experienced or sought—is more weighty than whatever negative effects those with more power may experience. Feminist Robin Morgan put it this way:

"And let's put one lie to rest for all time: the lie that men are oppressed, too, by sexism—the lie that there can be such a thing as 'men's liberation groups.' Oppression is something that one group of people commits against another group specifically because of a 'threatening' characteristic shared by the latter group—skin color or sex or age, etc."

Quotes on Sexism

Bell Hooks : "Simply put, feminism is a movement to end sexism, sexist exploitation, and oppression... I liked this definition because it did not imply that men were the enemy. By naming sexism as the problem it went directly to the heart of the matter. Practically, it is a definition that implies that all sexist thinking and action is the problem, whether those who perpetuate it are female or male, child, or adult. It is also broad enough to include an understanding of systemic institutionalized sexism. As a definition it is open-ended. To understand feminism it implies one has to necessarily understand sexism."

Caitlin Moran : “I have a rule for working out if the root problem of something is, in fact, sexism. And it is this: asking 'Are the boys doing it? Are the boys having to worry about this stuff? Are the boys the center of a gigantic global debate on this subject?”

Erica Jong : "Sexism kind of predisposes us to see men's work as more important than women's, and it is a problem, I guess, as writers, we have to change."

Kate Millett : "It is interesting that many women do not recognize themselves as discriminated against; no better proof could be found of the totality of their conditioning."

- Womanist: Definition and Examples

- Feminist Quotes from Famous Women

- 24 Andrea Dworkin Quotes

- Feminist Poetry Movement of the 1960s

- Lorna Dee Cervantes

- Biography of bell hooks, Feminist and Anti-Racist Theorist and Writer

- Combahee River Collective in the 1970s

- An Overview of Third-Wave Feminism

- Patriarchal Society According to Feminism

- Simone de Beauvoir and Second-Wave Feminism

- Quotes From Women in Black History

- 42 Must-Read Feminist Female Authors

- The Core Ideas and Beliefs of Feminism

- Top 20 Influential Modern Feminist Theorists

- Biography of Aileen Hernandez

- The Personal Is Political

- History & Society

- Science & Tech

- Biographies

- Animals & Nature

- Geography & Travel

- Arts & Culture

- Games & Quizzes

- On This Day

- One Good Fact

- New Articles

- Lifestyles & Social Issues

- Philosophy & Religion

- Politics, Law & Government

- World History

- Health & Medicine

- Browse Biographies

- Birds, Reptiles & Other Vertebrates

- Bugs, Mollusks & Other Invertebrates

- Environment

- Fossils & Geologic Time

- Entertainment & Pop Culture

- Sports & Recreation

- Visual Arts

- Demystified

- Image Galleries

- Infographics

- Top Questions

- Britannica Kids

- Saving Earth

- Space Next 50

- Student Center

- Introduction

Sexism and feminism

Sexism and the men’s movement, examples of sexism.

- Who were some early feminist thinkers and activists?

- What is intersectional feminism?

- How have feminist politics changed the world?

Our editors will review what you’ve submitted and determine whether to revise the article.

- Pressbooks @ Howard Community College - Feminism and Sexism

- Social Sciences LibreTexts - Feminism and Sexism

- Healthline - How to Recognize and Address Sexism — and When to Get Support

- Boston University - Sexism

- National Center for Biotechnology Information - PubMed Central - Insights into Sexism: Male Status and Performance Moderates Female-Directed Hostile and Amicable Behaviour

- European Institute for Gender Equality - Sexism at work: how can we stop it?

- Table Of Contents

A feminist study of gender in society needs concepts to differentiate and analyze social inequalities between girls and boys and between women and men that do not reduce differences to the notion of biology as destiny. The concept of sexism explains that prejudice and discrimination based on sex or gender, not biological inferiority, are the social barriers to women’s and girls’ success in various arenas. To overcome patriarchy in society is, then, to dismantle sexism in society. The study of sexism has suggested that the solution to gender inequity is in changing sexist culture and institutions.

Recent News

The disentanglement of gender (and thus gender roles and gender identities) from biological sex was an accomplishment in large part of feminism, which claimed that one’s sex does not predict anything about one’s ability, intelligence, or personality. Extracting social behaviour from biological determinism allowed greater freedom for women and girls from stereotypical gender roles and expectations. Feminist scholarship was able to focus study on ways in which the social world subordinated women by discriminating against and limiting them on the basis of their biological sex or of sociocultural gender-role expectations. The feminist movement fought for the abolishment of sexism and the establishment of women’s rights as equal under the law. By the remediation of sexism in institutions and culture, women would gain equality in political representation, employment, education, domestic disputes, and reproductive rights.

As the term sexism gained vernacular popularity, its usage evolved to include men as victims of discrimination and social gender expectations. In a cultural backlash, the term reverse sexism emerged to refocus on men and boys, especially on any disadvantages they might experience under affirmative action . Opponents of affirmative action argued that men and boys had become the ones discriminated against for jobs and school admission because of their sex. The appropriation of the term sexism was frustrating to many feminists, who stressed the systemic nature of women’s oppression through structural and historical inequalities. Proponents of men’s rights conjured the notion of misandry, or hatred of men, as they warned against a hypothesized approach of a female-dominated society.

As the academic discipline of women’s studies helped document women’s oppression and resilience , the men’s movement reasoned that it was time to document men’s oppression. Proponents called for research to address the limitations of gender roles on both sexes. Critical work on men began to examine how gender-role expectations differentially affect men and women and has since begun to focus on the concepts of hegemonic masculinity and hegemonic femininity to address the oppressive aspect as well as the agency aspect of gender conformity and resistance.

According to some, sexism can be found in many aspects of daily life. Education, for example, has often attracted particular attention. Sexual harassment and gender-biased treatment—male students are often encouraged to take classes in science, technology, engineering, and mathematics ( STEM ), while females are not—are seen as widespread problems. Furthermore, in many parts of the world, women are barred or discouraged from attending school. It is estimated that two-thirds of illiterate people worldwide are females. This inequality in education contributes to gender disparities in the workplace, which has also drawn claims of sexism. Activists often note discrepancies in salaries and occupations between genders. For example, in the early 21st century in the United States , women typically earned about 84 percent of what men received. Moreover, women were often excluded from certain jobs, especially those of leadership; as of 2019 less than 10 percent of CEOs of S&P 500 companies were female.

In addition, sexism has been seen as contributing to violence against women. Such violence, whether sexual or otherwise physical, is widely viewed as a global problem; indeed, an estimated one in three women experiences it at some point during her lifetime. It is often the product of societal norms based on sexist beliefs, including the idea that males have the right to discipline females and the idea that women often encourage the violence, which is frequently blamed on their wearing so-called provocative clothing.

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

11.2 Feminism and Sexism

Learning objectives.

- Define feminism, sexism, and patriarchy.

- Discuss evidence for a decline in sexism.

- Understand some correlates of feminism.

Recall that more than one-third of the public (as measured in the General Social Survey) agrees with the statement, “It is much better for everyone involved if the man is the achiever outside the home and the woman takes care of the home and family.” Do you agree or disagree with this statement? If you are like the majority of college students, you disagree.

Today a lot of women, and some men, will say, “I’m not a feminist, but…,” and then go on to add that they hold certain beliefs about women’s equality and traditional gender roles that actually fall into a feminist framework. Their reluctance to self-identify as feminists underscores the negative image that feminists and feminism hold but also suggests that the actual meaning of feminism may be unclear.

Feminism and sexism are generally two sides of the same coin. Feminism refers to the belief that women and men should have equal opportunities in economic, political, and social life, while sexism refers to a belief in traditional gender role stereotypes and in the inherent inequality between men and women. Sexism thus parallels the concept of racial and ethnic prejudice discussed in Chapter 7 “Deviance, Crime, and Social Control” . Both women and people of color are said, for biological and/or cultural reasons, to lack certain qualities for success in today’s world.

Feminism as a social movement began in the United States during the abolitionist period before the Civil War. Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Lucretia Mott were outspoken abolitionists who made connections between slavery and the oppression of women.

The US Library of Congress – public domain; The US Library of Congress – public domain.

In the United States, feminism as a social movement began during the abolitionist period preceding the Civil War, as such women as Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Lucretia Mott, both active abolitionists, began to see similarities between slavery and the oppression of women. This new women’s movement focused on many issues but especially on the right to vote. As it quickly grew, critics charged that it would ruin the family and wreak havoc on society in other ways. They added that women were not smart enough to vote and should just concentrate on being good wives and mothers (Behling, 2001).

One of the most dramatic events in the women’s suffrage movement occurred in 1872, when Susan B. Anthony was arrested because she voted. At her trial a year later in Canandaigua, New York, the judge refused to let her say anything in her defense and ordered the jury to convict her. Anthony’s statement at sentencing won wide acclaim and ended with words that ring to this day: “I shall earnestly and persistently continue to urge all women to the practical recognition of the old revolutionary maxim, ‘Resistance to tyranny is obedience to God’” (Barry, 1988).

After women won the right to vote in 1920, the women’s movement became less active but began anew in the late 1960s and early 1970s, as women active in the Southern civil rights movement turned their attention to women’s rights, and it is still active today. To a profound degree, it has changed public thinking and social and economic institutions, but, as we will see coming up, much gender inequality remains. Because the women’s movement challenged strongly held traditional views about gender, it has prompted the same kind of controversy that its 19th-century predecessor did. Feminists quickly acquired a bra-burning image, even though there is no documented instance of a bra being burned in a public protest, and the movement led to a backlash as conservative elements echoed the concerns heard a century earlier (Faludi, 1991).

Several varieties of feminism exist. Although they all share the basic idea that women and men should be equal in their opportunities in all spheres of life, they differ in other ways (Lindsey, 2011). Liberal feminism believes that the equality of women can be achieved within our existing society by passing laws and reforming social, economic, and political institutions. In contrast, socialist feminism blames capitalism for women’s inequality and says that true gender equality can result only if fundamental changes in social institutions, and even a socialist revolution, are achieved. Radical feminism , on the other hand, says that patriarchy (male domination) lies at the root of women’s oppression and that women are oppressed even in noncapitalist societies. Patriarchy itself must be abolished, they say, if women are to become equal to men. Finally, an emerging multicultural feminism emphasizes that women of color are oppressed not only because of their gender but also because of their race and class (Andersen & Collins, 2010). They thus face a triple burden that goes beyond their gender. By focusing their attention on women of color in the United States and other nations, multicultural feminists remind us that the lives of these women differ in many ways from those of the middle-class women who historically have led U.S. feminist movements.

The Growth of Feminism and the Decline of Sexism

What evidence is there for the impact of the women’s movement on public thinking? The General Social Survey, the Gallup Poll, and other national surveys show that the public has moved away from traditional views of gender toward more modern ones. Another way of saying this is that the public has moved toward feminism.

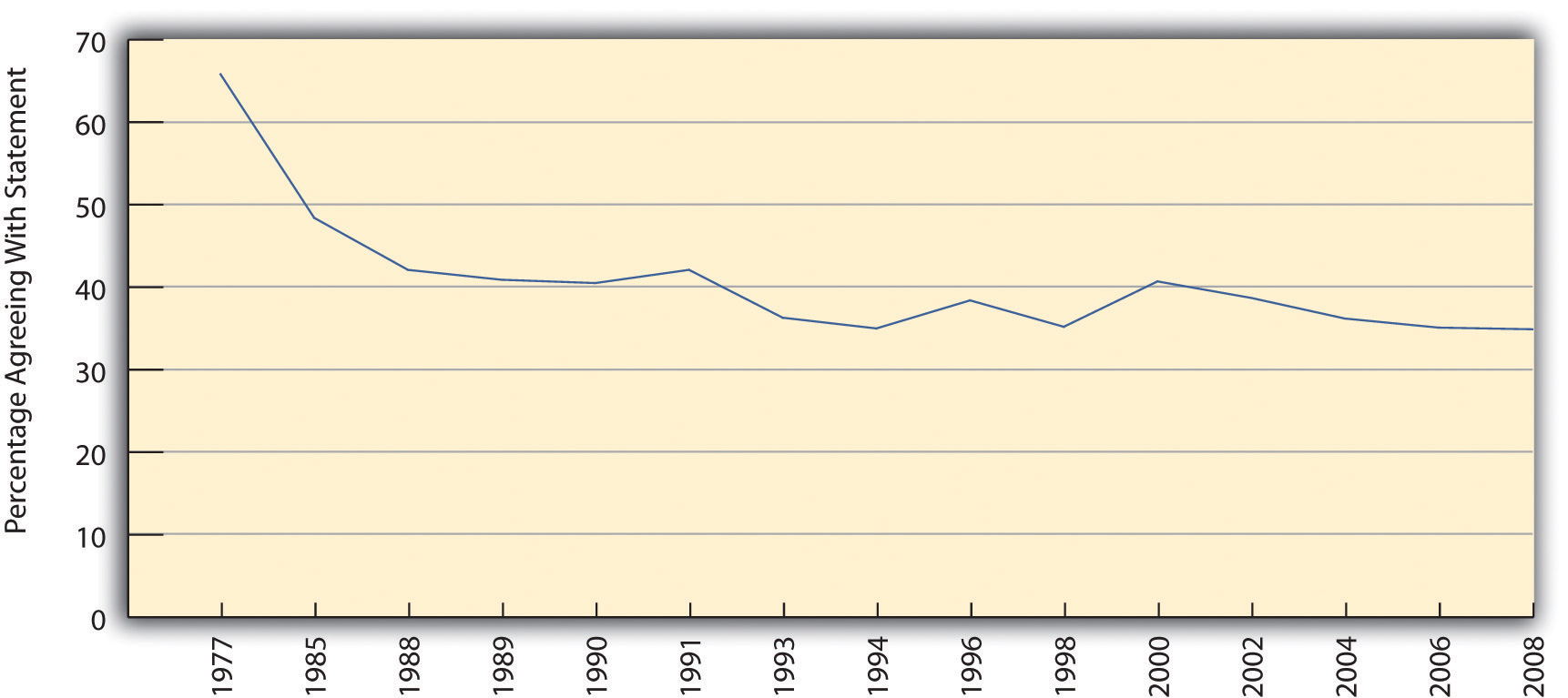

To illustrate this, let’s return to the General Social Survey statement that it is much better for the man to achieve outside the home and for the woman to take care of home and family. Figure 11.4 “Change in Acceptance of Traditional Gender Roles in the Family, 1977–2008” shows that agreement with this statement dropped sharply during the 1970s and 1980s before leveling off afterward to slightly more than one-third of the public.

Figure 11.4 Change in Acceptance of Traditional Gender Roles in the Family, 1977–2008

Percentage agreeing that “it is much better for everyone involved if the man is the achiever outside the home and the woman takes care of the home and family.”

Source: Data from General Social Survey.

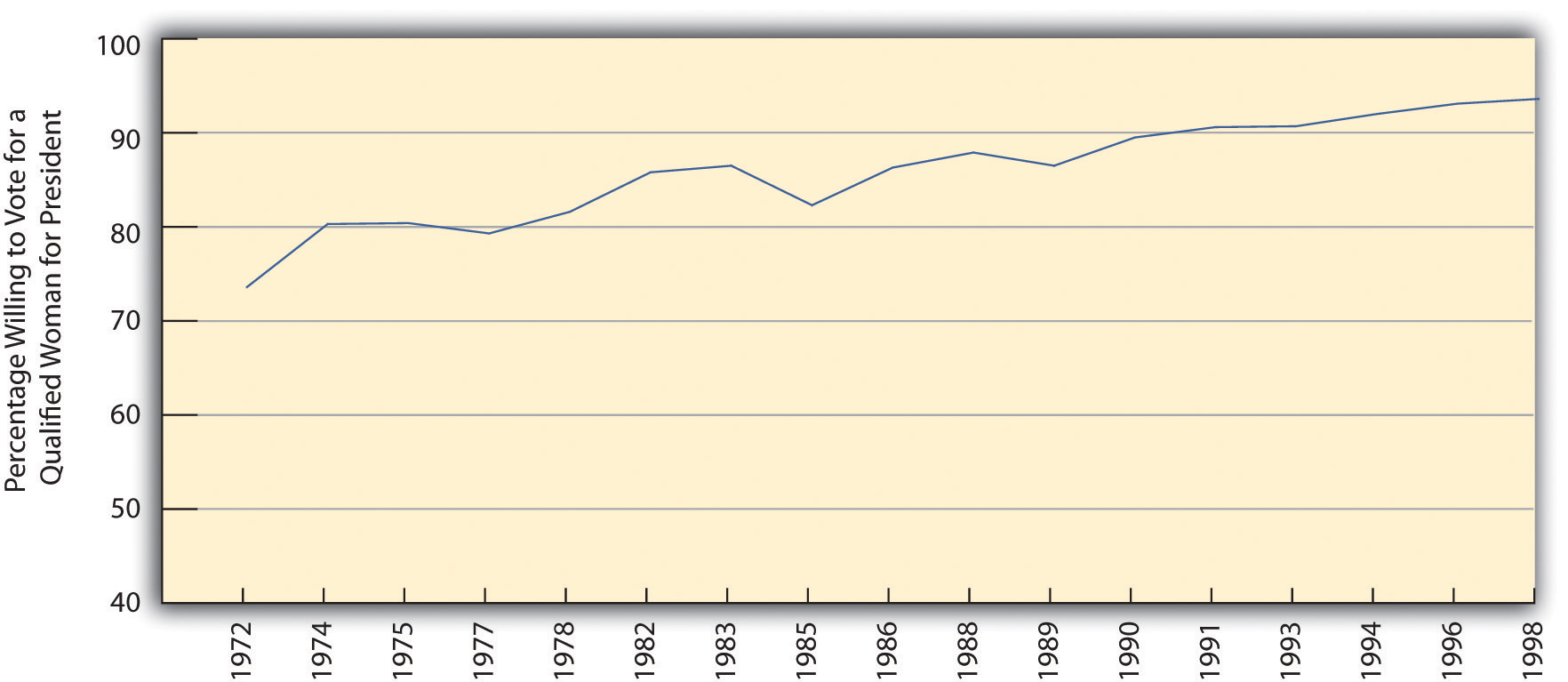

Another General Social Survey question over the years has asked whether respondents would be willing to vote for a qualified woman for president of the United States. As Figure 11.5 “Change in Willingness to Vote for a Qualified Woman for President” illustrates, this percentage rose from 74% in the early 1970s to a high of 94.1% in 2008. Although we have not yet had a woman president, despite Hillary Rodham Clinton’s historic presidential primary campaign in 2007 and 2008 and Sarah Palin’s presence on the Republican ticket in 2008, the survey evidence indicates the public is willing to vote for one. As demonstrated by the responses to the survey questions on women’s home roles and on a woman president, traditional gender views have indeed declined.

Figure 11.5 Change in Willingness to Vote for a Qualified Woman for President

Correlates of Feminism

Because of the feminist movement’s importance, scholars have investigated why some people are more likely than others to support feminist beliefs. Their research uncovers several correlates of feminism (Dauphinais, Barkan, & Cohn, 1992). We have already seen one of these when we noted that religiosity is associated with support for traditional gender roles. To turn that around, lower levels of religiosity are associated with feminist beliefs and are thus a correlate of feminism.

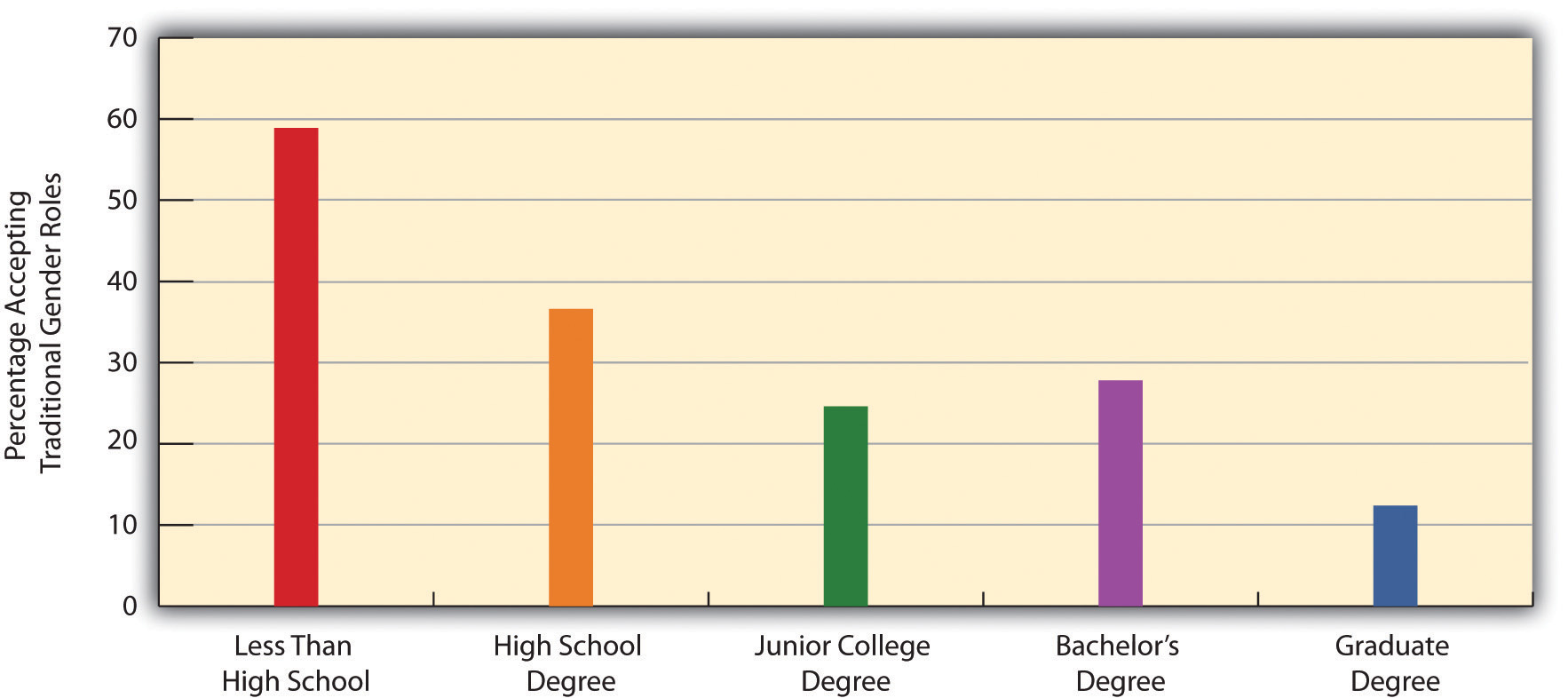

Several other such correlates exist. One of the strongest is education: the lower the education, the lower the support for feminist beliefs. Figure 11.6 “Education and Acceptance of Traditional Gender Roles in the Family” shows the strength of this correlation by using our familiar General Social Survey statement that men should achieve outside the home and women should take care of home and family. People without a high school degree are almost 5 times as likely as those with a graduate degree to agree with this statement.

Figure 11.6 Education and Acceptance of Traditional Gender Roles in the Family

Source: Data from General Social Survey, 2008.

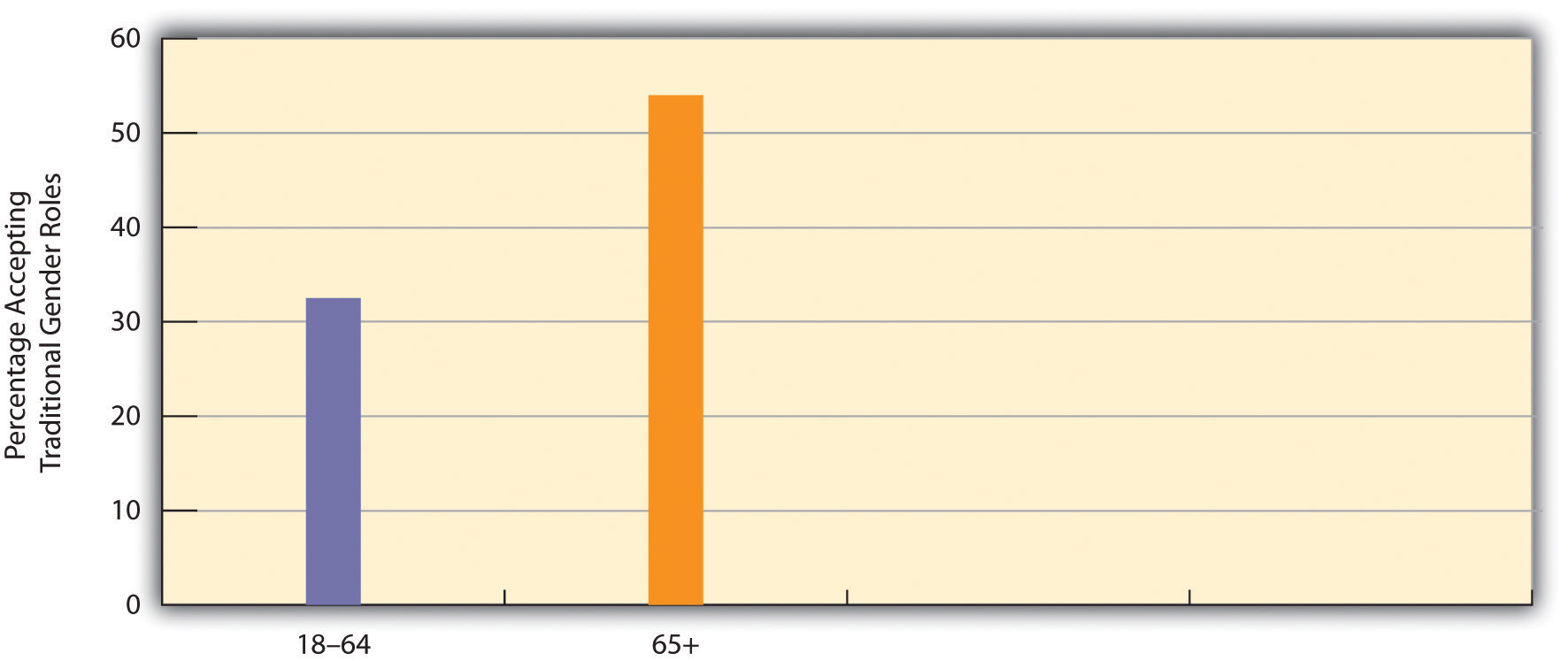

Age is another correlate, as older people are more likely than younger people to believe in traditional gender roles. Again using our familiar statement about traditional gender roles, we see an example of this relationship in Figure 11.7 “Age and Acceptance of Traditional Gender Roles in the Family” , which shows that older people are more likely than younger people to accept traditional gender roles as measured by this statement.

Figure 11.7 Age and Acceptance of Traditional Gender Roles in the Family

Key Takeaways

- Feminism refers to the belief that women and men should have equal opportunities in economic, political, and social life, while sexism refers to a belief in traditional gender role stereotypes and in the inherent inequality between men and women.

- Sexist beliefs have declined in the United States since the early 1970s.

- Several correlates of feminist beliefs exist. In particular, people with higher levels of education are more likely to hold beliefs consistent with feminism.

For Your Review

- Do you consider yourself a feminist? Why or why not?

- Think about one of your parents or of another adult much older than you. Does this person hold more traditional views about gender than you do? Explain your answer.

Andersen, M. L., & Collins, P. H. (Eds.). (2010). Race, class, and gender: An anthology (7th ed.). Belmont, CA: Wadsworth.

Barry, K. L. (1988). Susan B. Anthony: Biography of a singular feminist . New York, NY: New York University Press.

Behling, L. L. (2001). The masculine woman in America, 1890–1935 . Urbana: University of Illinois Press.

Dauphinais, P. D., Barkan, S. E., & Cohn, S. F. (1992). Predictors of rank-and-file feminist activism: Evidence from the 1983 General Social Survey. Social Problems, 39 , 332–344.

Faludi, S. (1991). Backlash: The undeclared war against American women . New York, NY: Crown.

Lindsey, L. L. (2011). Gender roles: A sociological perspective (5th ed.). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall.

Sociology Copyright © 2016 by University of Minnesota is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

- Choose language

- Azərbaycanca

- Nedersassisch

Sexism is any expression (act, word, image, gesture) based on the idea that some persons, most often women, are inferior because of their sex.

Sexism is harmful . It produces feelings of worthlessness, self-censorship, changes in behaviour, and a deterioration in health. Sexism lies at the root of gender inequality. It affects women and girls disproportionately.

Sexism is present in all areas of life.

63% of women journalists have been confronted with verbal abuse

Women spend almost twice as much time as men on unpaid housework (OECD countries)

80% of women stated that they have been confronted with the phenomenon of “mansplaining” and “manterrupting” at work

Men represent 75% of news sources and subjects in Europe

In the UK, 66% of 16-18-year-old girls surveyed experienced or witnessed the use of sexist language at school

59% of women in Amsterdam reported some form of street harassment

In France, 50% of young women surveyed recently experienced injustice or humiliation because they are women

In Serbia, research indicates that 76% of women in business are not taken as seriously as men

Violence sometimes starts with a joke

Individual acts of sexism may seem benign, but they create a climate of intimidation, fear and insecurity. this leads to the acceptance of violence , mostly against women and girls..

This is why the Council of Europe has decided to act by adopting a Recommendation to prevent and combat sexism .

Sexism affects mostly women. It can also affect men and boys when they don’t conform to stereotyped gender roles.

The harmful impact of sexism can be worse for some women and men due to their ethnicity, age, disability, social origin, religion, gender identity, sexual orientation or other factors.

Some groups of women, for example young women, politicians, journalists or public figures, are particular targets of sexism

of women elected to Parliament have been the target of sexist attacks on social networks

See it. Name it. Stop it.

Language and communication.

Examples of sexism in language and communications:

The generic use of the masculine gender by a speaker (“he/his/him” to refer to an unspecific person). The cover of a publication depicting men only . The naming of a woman by the masculine term for her profession. A communication campaign including gratuitous nudity . An advertisement with a man showing a woman how to use a washing machine.

Why should it be addressed?

Language and communication matter because they make people visible or invisible and recognise or demean their contribution to society. Our language shapes our thought , and the way we think influences our actions. Gender-blind or discriminatory language reinforces sexist attitudes and behaviour.

How to prevent it?

Use both the feminine and the masculine when addressing a mixed audience. Review public communication to make sure it uses gender-sensitive language and imagery. Produce manuals on gender-sensitive communication for different audiences. Promote research in this area.

Media, Internet and social media

Examples of sexism in the media:

A sexualised depiction of women in the media. An all-male TV show. Media reporting on violence against women which blames the victim . Journalists, most often women, receiving comments on social media based on their appearance instead of the issues they discuss. Internet applications sending some job adverts to men only because algorithms are built in a discriminatory way.

Children and others are bombarded with sexist media messages and influenced by them. Such messages limit their own choices in life. They give the impression that men are the keepers of knowledge and power and that women are objects and it’s ok to comment freely on their appearance. Online sexism pushes women out of online spaces . Online sexism can cause very real harm. Abusing or mocking someone online creates a permanent digital record that can be further disseminated and is difficult to erase.

Implement legislation on gender equality in media . Train media and communication professionals on gender equality. Ensure that women and men are represented in a balanced way and in diverse, non-stereotypical roles in the media . Promote advertisements that play with, and raise awareness of, gender stereotypes rather than reinforce them. Provide digital literacy training especially for young people and children. Legally define and criminalise (online) sexist hate speech . Put in place specialised services to provide advice on how to deal with online sexism .

Examples of sexism at the workplace:

The practice of unofficially excluding women who have children from career opportunities. In meetings, ignoring women , appropriating their contributions or silencing them. Favouring a man rather than a woman for a managerial position by presuming her lack of authority . Gratuitous comments about physical appearance or dress (which undermine women as professionals). Derogatory comments to men taking on caring roles. “ Mansplaining ”.

Workplace sexism undermines the efficiency of victims and their sense of belonging. Silencing through sexism means that ideas or talents are ignored or under-used. Belittling comments create an intimidating/oppressive atmosphere for those confronted with them and can degenerate in violence/harassment . Victims may develop higher anxiety levels , be more prone to outbursts and depression. More generally, sexism leads to lower salaries and fewer opportunities for those confronted with it.

Adopt and implement codes of conduct defining sexist behaviour and prevent it through training. Put in place complaint mechanisms , disciplinary measures and support services. Managers must state and show their commitment to act against sexism .

Public sector

Examples of sexism in the public sector:

Sexualised comments or comments about the appearance or family situation of politicians, most often women, including within parliaments. Comments about the sexual orientation or appearance of users by staff of public services. Sexist representations / posting of images of naked women in public workplaces (e.g. hospital staff rooms). Comments on women’s appearance in public spaces, including public transport.

The public sector has a duty to lead by example . Sexism in parliaments is very common but it limits the opportunities and freedom of women in parliaments, be they elected or staff. Sexism undermines equal access to public services . Sexism in public spaces limits women’s freedom of movement. Sexism can lead to violence and creates an oppressive environment preventing mostly women from fully participating in public life.

Training of staff. Put in place codes of conduct , complaint mechanisms, disciplinary measures and support services. Implement awareness raising campaigns , such as toolkits or posters in public space explaining what sexism is. Promote gender balance in decision-making . Promote research and the gathering of data on the issue.

Examples of sexism in the justice system:

A judge implying to a victim of sexual violence that she was ‘asking for it’ . A law professional commenting on the appearance of a woman who is a colleague. A police officer not taking an allegation of violence against women seriously or trivialising it.

Such behaviour can lead to victims dropping cases . They create distrust in the justice system. They can lead to misinformed judgments . They demean women and can push them out of legal professions .

Implement policies on women’s equal access to justice . Train legal and law enforcement professionals. Deconstruct judicial stereotyping through awareness-raising campaigns. Ensure professionals base their judgments on facts , on the behaviour of the perpetrator and the context of the case rather than the victim’s clothing, for example.

Examples of sexism in education:

Textbooks containing stereotypical images of women/men, boys/girls. The absence of women as writers, historical or cultural figures in textbooks . Career and education counselling discouraging non-stereotypical career or study choices . Teachers making comments about the appearance of pupils/students/fellow teachers. Sexualised comments to girls. Bullying of non-conforming pupils /students by fellow pupils /students or education professionals. The absence of awareness /procedures / reactions to address such sexist behaviour.

The content of education and behaviour of education professionals heavily influences perceptions and behaviour . A climate of sexism in learning establishments negatively affects the achievements of pupils/students. Sexism in education can limit future individual career and lifestyle choices .

Implement policies and legislation on gender equality in education . Review textbooks to ensure that they are free of sexism and that they depict women as well as men in non-stereotypical roles. Ensure the representation of women as scientists, artists, athletes, leaders, politicians in textbooks and programmes . Teach women’s history . Ensure the availability of complaint mechanisms. Teach gender equality issues as well as sexuality education (including consent and personal boundaries). Train education professionals on unconscious bias .

Culture and sport

Examples of sexism in culture and sport:

Sportswomen depicted in the media according to their family role and not their skills and strengths. Trivialising women’s sporting achievements . Demeaning men who play “feminine” sports. Women in sexy outfits as “decoration” in cultural or sporting events. Absence of women’s work in art exhibitions. Scarcity of meaningful roles for women in cinema and the virtual absence of roles for older actresses. Scarcity of funding for film production in which women have a leadership role. Under-resourcing of women’s art.

Both culture and sport are shapers of attitudes . If women and men are depicted in stereotyped ways, this will feed into gender stereotyping. When mostly men are visible in these areas, this influences the way women are seen as potential artists or athletes and narrows the range of role models for children and young people. Gender stereotypes limit the choice of women/men girls/boys to practice sports that are not considered “feminine” or “masculine” ; this leads to self-censorship . In both areas, sexism leads to lower salaries and fewer opportunities for those confronted with it.

Measures to encourage creative work by women and gender mainstreaming in cultural and sport policies (scholarships, exhibitions, training, provision of space/workshops). Ensure better and more media coverage of women’s sports and art. Encourage sponsors to support women’s arts and sports. Adopt codes of conduct to prevent sexist behaviour, including provision for disciplinary action in sports federations. Encourage leading sport and cultural figures to speak up against sexism and implement campaigns to denounce violence in sport and sexist hate speech.

Private sphere

Examples of sexism in the private sphere:

Women performing more unpaid (care and household) work than men, for example only women helping to wash dishes at a dinner party. Sexist jokes between friends. Systematically offering “feminine” or “masculine” toys to girls/boys. Boys being encouraged to run and take risks and girls to be docile and compliant. The use of expressions like “running like a girl” or “boys will be boys”.

Unpaid work weighs on women’s participation in the labour market, on their economic independence as well as on their participation in sport and leisure activities. Toys (e.g. a mini kitchen or a construction game) influence gender roles, but also future study or career choices. Sexist jokes can intimidate and silence people and they trivialise sexist behaviour.

Awareness-raising measures and research on the impact and the sharing of unpaid work between women and men. Measures for reconciling private and working life for all . Promotion of non-gendered toys . Encouraging boys as well as girls to participate in household tasks. Giving girls , too, the space and freedom to play, explore and be themselves.

D iscover Society

Measured – factual – critical.

- Covid-19 Chronicles

- Policy & Politics

Sexism in language: A problem that hasn’t gone away

- By discoversociety

- March 01, 2016

- 2016 , Articles , Issue 30

Deborah Cameron

2016 marks the 40 th anniversary of the publication of Casey Miller and Kate Swift’s Words and Women . Described on its cover as a ‘landmark work that reveals the sexual biases present in our everyday speech and writing’, this second-wave feminist classic drew attention to the pervasiveness of what feminists dubbed ‘ he-man language ’ (the conventional use of ‘he’ and ‘man’ in generic references to mixed groups, as in ‘man has always adapted to his environment’), and to the routine occurrence in journalism of formulas that either defined women by their familial roles (‘mother-of-two breaks speed record’), or else objectified, sexualised and demeaned them (‘vice-girl arrested’; ‘gentlemen prefer blondes’). In feminist circles these complaints were already familiar; but books like Words and Women, accessibly written for a general audience, helped to bring the issue of sexist language into the mainstream.

In those days the mainstream was not unreceptive. Changes in conventional usage always provoke resistance, and the reforms proposed by feminists were no exception. But many influential gatekeepers were sympathetic to the feminist argument. Advice on avoiding sexist language began to appear routinely in publishers’ and newspapers’ style guides, college writing handbooks and standard reference works on usage. By the end of the 1980s it seemed the battle had largely been won—all feminists and their supporters had to do was wait for the remaining dinosaurs to become extinct.

But as it turned out, it wasn’t quite that simple.

One problem which arose early on was a tendency to water down the original feminist analysis by equating ‘non-sexist’ language with what is now often called ‘ gender fair’ or ‘inclusive’ terminology. What feminists had originally coined the term ‘sexism’ to describe was a systemic structural inequality between men and women; but as the concept entered mainstream thinking it came to be understood in more liberal terms, as meaning any kind of unequal or differential treatment on the grounds of sex. This understanding, which presupposes that sexism affects both sexes equally, was reflected in legislation, such as the Sex Discrimination Act which was passed in Britain in 1975 . The Act had a linguistic dimension, in that it required job advertisements to make clear in their wording that positions were open to applicants of both sexes. The result was to favour the use of neutral or inclusive terms over other strategies which feminists had developed (such as the ‘visibility strategy’ of using language that deliberately calls attention to the presence of women, or treats women rather than men as the norm). Over time, this preference has become entrenched: any attempt to counter sexism by departing from the inclusiveness principle is liable to attract the criticism that it treats men unfairly and is therefore sexist itself.

In some contexts (including job advertisements), inclusive language is a reasonable strategy for countering sexism. In others, however, it tends to obscure the structural inequalities that were foregrounded in feminist analysis. An example is the proliferation of inclusive terms like ‘ gender-based violence ’ and ‘intimate partner killing’, which are now part of the official language used by government agencies, NGOs and transnational bodies like the UN. These terms can imply that women are as likely to harm or kill men as vice-versa, when in reality virtually all ‘gender-based violence’, especially where it involves repeated and/or serious offences, is in fact male violence against women . Also ubiquitous nowadays are references to ‘parents’ and ‘parenting’: though this is an area where inclusive terminology can be useful, the automatic use of neutral terms obscures the fact that childcare continues to be disproportionately the responsibility of mothers .

Since it was first taken up as an issue, the progress of non-sexist language reform has also been affected by various changes in the political weather. In the 1970s and 1980s feminism was a significant political and cultural force, but its influence weakened during the 1990s. Younger women were repudiating the ‘F-word’, a new ‘lad culture’ was on the rise, and pundits proclaimed the onset of a ‘post-feminist’ era. At the same time, there was a concerted attack on so-called ‘political correctness’, and the alleged policing of language by a motley crew of feminists, LGBT activists, anti-racists and multiculturalists promoting extreme and restrictive speech-codes. Though non-sexist language policies had been around for two decades, and had not been considered ‘extreme’ by the many mainstream organizations which had adopted them, in this new climate they became suspect by association.

This change in mood was reflected not only in attitudes to the project of language reform, but also in everyday language-use. Some quantitative analyses of corpus data from the late 20 th century (a ‘corpus’ is a large, computer-searchable sample of authentic usage, selected to be representative of the language in question) suggest that trends which were noticeable in the 1970s and 80s, such as a rise in the use of ‘he or she’ rather than ‘he’ in formal written texts, were starting to be reversed by the turn of the millennium. Evidently the cultural pressure to avoid sexism was not maintained for long enough for new conventions to become naturalized: as the pressure decreased, the old habits of usage crept back. Of course, there were parts of the culture where they had never really gone away; but it is noticeable that ‘he-man’ language has returned to some of the areas which most decisively rejected it in the past.

Universities are one example: research suggests that the shift away from ‘he’ in the 1970s and 80s was most pronounced in academic writing, but as a university teacher today, I rarely encounter a student who does not use the generic masculine. Similarly, few of my colleagues raise an eyebrow when faced with references to the ‘chairman’ of a committee, even when the person in question is female. The mass media are another domain where there seems to be less awareness of the issue now than there was at some points in the past. Again, it is true that there was never much awareness of it in some parts of the media (especially the press): it was no surprise when, in 2014, the Daily Mail reported the choice of Rev. Libby Lane as England’s first female Anglican bishop under the headline ‘ Saxophone playing vicar’s wife is C of E’s first woman bishop ’. But broadcast news outlets which do not share the Mail’s conservatism can also display a surprisingly old-fashioned turn of phrase. As I write, one of the day’s main news stories concerns a clinical trial in which several volunteers suffered brain-damage after taking an experimental drug: the news bulletin I watched explained that it was not the first time the drug had been tested ‘in man’. (In fairness, I heard another which used the phrase ‘on humans’, but the point is that ‘man’ has not withered away as feminists 40 years ago imagined it would.)

In the 21 st century there has been a notable resurgence of feminist political activism. But the form in which feminism has returned is, inevitably, different from the form it took in the past. One development that has affected attitudes to language is the rise of a new kind of gender identity politics. Today the most vocal demands for linguistic reform come from trans, non-binary and genderqueer activists; and when they call for ‘inclusive’ language, what they mean is not language that includes women as well as men, but language that includes people of all genders and none.

This new version of the inclusiveness principle can be in severe tension with the older feminist aim of using language to raise women’s status and visibility. Recently, the desire to avoid language deemed ‘trans exclusionary’ has led a number of women’s organizations, from Britain’s National Union of Students Women’s Campaign to the Midwives’ Association of North America , to move away from female-specific language, abandoning expressions like ‘sister(hood)’ in favour of the more ‘inclusive’ ‘siblinghood’, and substituting ‘people’ or ‘individuals’ for ‘women’ in the phrase ‘pregnant ____’. There have also been proposals to redesign official documents such as UK passports, drivers’ licenses and university application forms so that an individual’s gender no longer has to specified—though some feminists have expressed concern that this change would make it harder to access full and accurate information relating to areas where we know there are continuing problems of sex inequality and discrimination.

On the other hand, some non-sex-specific terms originally proposed by feminists have been successfully revived by supporters of the new gender identity politics. For instance, it was 1970s feminists who first argued for ‘they’ to be accepted in its (historically well-established) use as a singular third person pronoun ; the non-sex-specific courtesy title ‘Mx’ was also created in the 1970s as a more radical non-sexist alternative than ‘Ms’ to ‘Mr/Mrs/Miss’ (the first known use of it appeared in a 1977 magazine for single parents). Though both proposals met with strong resistance at the time, they have now won the support of influential gatekeepers. In 2015 the Washington Post accepted singular ‘they’ as a legitimate usage , while the title ‘Mx’ is now offered as an option by mainstream institutions including universities, banks, the UK’s Department of Work and Pensions and the Royal Mail.