Instantly enhance your writing in real-time while you type. With LanguageTool

Get started for free

Fiction and Nonfiction: Understanding the Distinctions

Becoming a skilled writer requires knowing the different genres available. Let’s start with the basics: understanding the difference between fiction and nonfiction.

What’s the Difference Between “Fiction” and “Nonfiction”?

Fiction refers to “something created in the imagination .” Therefore, fictional writing is based on events that the author made up rather than real ones. Nonfiction is “writing that revolves around facts , real people, and events that actually occurred .”

Table of Contents

What does “fiction” mean (with examples).

What Does “Nonfiction” Mean? (With Examples)

How To Write Fiction and Nonfiction Masterpieces

An artist discerns subtle brushstrokes that look identical to the average person. They can also recognize hundreds of colors by their names. Similarly, as writers, we must be familiar with distinct types of prose, with the foundation of that knowledge being the ability to differentiate between fiction and nonfiction .

If you’ve ever been uncertain about these terms, you’re in the right place. We’ll help you get a solid grasp of what fiction and nonfiction mean by providing clear explanations and examples.

Let’s dive in!

Fiction is “written work that is invented or created in the mind.” Put differently, the narrative is imaginary and didn’t actually happen. Novels, short stories, epic poems, plays, and comic books are a few types of fiction writing.

Examples of famous fiction literature include:

Alice in Wonderland by Lewis Carroll

Animal Farm by George Orwell

Fahrenheit 451 by Ray Bradbury

The Harry Potter Series by J.K. Rowling

Don Quixote de la Mancha by Miguel de Cervantes

Fiction can read like this:

On my way to the city of Bolognaland, I noticed that my water-fueled flying car was running low on energy. So, I stopped by the water station and filled up the tank. There, I saw the most beautiful sunset of green, turquoise, and black. As the sun set below the horizon, the two moons—Luminara and Crescelia—took their place in the night sky.

To the best of our knowledge, every single aspect of the story written above is imaginary, from Bolognaland to the two moons. However, it’s important to note that not every component of a fictional story has to be created out of thin air. For example, someone could come up with a tale about a man who grew up in Cleveland, Ohio, which is an actual place in the United States. A fictional story can incorporate many components that are nonfiction .

The word fiction isn’t always used to describe a type of literature; it can also refer to anything false.

Don’t believe anything he says—it’s all fiction !

The legend of the hidden treasure has been passed down in this family for generations, but most of us think it’s fiction .

A main part of my job as a historian is to separate fact from fiction in ancient manuscripts.

“Fictional” vs. “Fictitious”

Fictional and fictitious both relate to things or people that are made up and are often used interchangeably. However, fictional typically describes something that originates from literature , movies , or other forms of storytelling , and fictitious can refer to something that is false and intended to deceive . In other words, it carries more of a negative connotation.

What Does “Nonfiction” Mean?

Nonfiction refers to “literature that is based on facts, real events, and real people.” Nonfiction writers aim to compose everything as truthfully and accurately as possible. However, sometimes authors enhance certain parts to make them more interesting, or they are required to change specific facts, like names, for privacy reasons.

Memoirs, biographies, articles, essays, and even personal journal entries are a few types of nonfiction texts.

A few examples of famous published nonfiction works include:

Elon Musk by Walter Isaacson

When Breath Becomes Air by Paul Kalanithi

The Diary of a Young Girl by Anne Frank

Educated by Tara Westover

The Hidden Life of Trees by Peter Wohlleben

Here’s a piece of nonfiction text:

Elon Musk was born in Pretoria, South Africa on June 28, 1971. His mother is Maye Musk, and his father is Errol Musk. Musk has two siblings, a younger brother named Kimbal and a younger sister named Tosca.

This text is accurate and based on facts; therefore, it is considered nonfiction . But please note that it is not exemplary of nonfiction works—they’re not all boring, rigid, and monotonous. Skilled nonfiction writers weave rhetorical devices, interesting facts, and more to keep readers engaged.

Is it “Nonfiction” or “Non-Fiction”?

This word can be spelled as a hyphenated ( non-fiction ) or non-hyphenated ( nonfiction ) compound word . The spelling depends on which English dialect you’re writing in.

In American English, nonfiction is more commonly used. Both forms are found in British English, but non-fiction is slightly more prevalent.

How To Write Fictional and Nonfictional Masterpieces

We should reiterate that fiction and nonfiction writing can overlap. That means that some fiction includes components of nonfiction and vice versa .

What’s vital to remember is that fiction writing is mostly made up of fabricated stories, whereas nonfiction writing is mostly composed of the truth.

Written masterpieces can be found in all genres, including fiction and nonfiction . When it’s time for you to work on yours, make sure you entrust LanguageTool as your writing assistant. As a multilingual, AI-driven, spell, grammar, and punctuation checker, LanguageTool rids your texts of various types of errors while ensuring you stay productive to reach your goals.

Give it a try today to start writing like the legends!

Unleash the Professional Writer in You With LanguageTool

Go well beyond grammar and spell checking. Impress with clear, precise, and stylistically flawless writing instead.

Works on All Your Favorite Services

- Thunderbird

- Google Docs

- Microsoft Word

- Open Office

- Libre Office

We Value Your Feedback

We’ve made a mistake, forgotten about an important detail, or haven’t managed to get the point across? Let’s help each other to perfect our writing.

Works of prose are typically divided into one of two categories: fiction vs. nonfiction. A work of fiction might resemble the real world, but it certainly did not happen in real life. Nonfiction, on the other hand, should not contain any fiction, as the writer’s credibility comes from the truthfulness of the story.

Any writer of fiction vs. nonfiction will use different skills and strategies to write in each genre. Yet, fiction and nonfiction are more alike than you might realize. Additionally, there are many works of prose that fall somewhere in between the fiction vs. nonfiction binary.

This article examines, in detail, the writing strategies available to prose writers of fiction and nonfiction. It also examines the fiction vs. nonfiction binary, and offers insight into the role that “truth” plays in both genres of literature.

But first, let’s uncover what writers mean when they categorize a work of prose as fiction vs. nonfiction. What is the difference between fiction and nonfiction?

Fiction vs. Nonfiction: Definitions

Let’s begin by defining each of these categories of literature. The main difference between fiction and nonfiction has to do with “what actually transpired in the real world.”

“Fiction” refers to stories that have not occurred in real life. Fiction may resemble real life, and it may even pull from real life events or people. But the story itself, the “what happens in this text,” is ultimately invented by the author.

“Nonfiction,” on the other hand, refers to stories that have occurred in real life. The story may have happened in the author’s life, in the life of someone the author has interviewed, or in the life of a historical figure. It also describes works of journalism, science writing, and other forms of “reality-based” writing.

To further complicate things, writers might categorize something as being either “ creative nonfiction ” or, simply, “nonfiction.” This article discusses strategies for writing both, but with an emphasis on creative nonfiction, such as memoir and personal essays, as those skills apply to most forms of prose.

Fiction vs. Nonfiction: A way of categorizing literature based on whether it happened in the real world (nonfiction) or didn’t (fiction).

Now, while these two categories exist, it’s worth noting that certain genres of writing sit somewhere in the middle. Some genres that straddle the fiction vs. nonfiction border are:

- Autobiographical fiction (also known as autofic). An example is The Idiot by Elif Batuman.

- Speculative nonfiction , or writing in which invented truths are not at odds with what transpired in real life.

- Historical fiction, which typically involves the accurate retelling of real life historical events, with fictional characters and plots woven through that history.

But wait, how can a work of literature be both true and not true? We’ll explore that paradox later in this article. First, let’s explore the possibilities of fiction and nonfiction.

Fiction vs. Nonfiction: Examples of Each Category

The following genres can be classified as types of fiction:

- Short stories.

- Plays and screenplays (though these can also be nonfiction).

- Literary fiction.

- Categories of genre fiction – including mystery, thriller, romance, horror, and other types of speculative fiction , like magical realism or urban fantasy .

- Fables, fairy tales, and folklore.

- Narrative poetry .

Meanwhile, these are different types of nonfiction:

- Personal essays.

- Biographies and autobiographies.

- Books about history.

- Periodicals.

- Lyric essays .

- Journalism, articles, food writing , travel writing, and other forms of feature writing.

- Scholarly articles.

Learn more about different types of nonfiction here:

https://writers.com/types-of-nonfiction

Characteristics of Fiction vs. Nonfiction

As you can see above, fiction and nonfiction are both expansive categories of literature. So, it’s impossible to describe all of fiction or nonfiction as being any particular thing. If I were to say “all fiction is about stories that haven’t actually happened,” that isn’t true, because genres like autofic and historical fiction exist.

Nonetheless, there are a few differences and similarities that can generally be stated about fiction vs. nonfiction. The differences include:

- Whether the story is made up or real.

- How the writer creates a plot for the story.

- The role research plays in telling the story.

- How themes are explored within the story.

Fiction vs. Nonfiction: Did It Actually Happen?

As we’ve already mentioned, the main difference between fiction and nonfiction is whether or not the story occurred in real life. In nonfiction, the story did occur in the real world; in fiction, it did not.

Fictional stories can be rooted in real-life events, but the scenes, plotline, and characters are invented by the author, even if they’re based on real people.

You might think of a couple of exceptions here. Historical fiction, for example, is often based on real historical events, such as Civil War stories. While the setting for the story happened in real life, and might even involve real historical figures, there are also fictional characters in the story, and the majority of scenes and plot points were fictionalized as well. If historical fiction interests you, check out our interview with Jack Smith on his novel If Winter Comes .

Another exception, in all seriousness, is fanfiction. Yes, Harry Styles fanfiction does involve a living, real life person. But the author is making assumptions, assigning character traits, and inventing plot points for Harry Styles that did not actually occur in the real world.

The point: fiction writers can (and always do!) borrow from real life. They might even tell their own stories as though they were fiction. Even in those instances, there are always details that are added, embellished, or altered to tell a more engaging story, so the stories themselves are still fictional.

Fiction vs. Nonfiction: What’s the Plot?

Fiction writers use plot as scaffolding for a story. By plot, we mean the way that the events of a story are organized from start to finish. Our article on plot structures offers different ways that fiction writers have used plot to tell their stories.

This is true even of literary fiction, which is typically defined as realistic fiction in which the characters’ decisions drive the story forward, and the characters themselves form the story. (This is a somewhat problematic distinction between genre fiction, but we discuss that in our article on literary fiction vs. genre fiction .) In those stories, plot is centered around the conflict in the story itself.

In nonfiction, the author’s goal is to organize what actually transpired in the real world into a cogent plot. For many writers, that means telling the story in a linear fashion, with careful attention to the most salient details and how they’re presented to the reader.

Of course, many creative nonfiction writers do tell stories non-linearly, particularly in genres like the braided essay, lyric essay, and hermit crab essay.

Fiction vs. Nonfiction: The Role of Research

Most prose writers will have to do some amount of research to craft effective works of fiction and nonfiction. Memoirists may be able to tell their story entirely without research, but anything to verify the accuracy of information counts as research, such as looking up old emails, the streets and locations of certain events, etc. Rarely can one’s memory suffice to tell an entire story.

Fiction writers integrate their research into the story. Let’s say your story is set in New York, a city you’ve visited, but never lived in. You have a character that lives in Bushwick, which is served by the L, M, J, and Z trains. You may need to research that, and when that research is integrated into the story, you’ll write that your character “took the L train.” (In other words, you will not write “I discovered that Bushwick is served by the L train, which my character took into Manhattan.”)

In nonfiction, research informs the story, and is directly cited in the text. Let’s say your story involves New York rent and the aforementioned L train. You might be writing about the time that the city almost shut down the L train—they needed to do repairs to the tunnel beneath the East River connecting Manhattan and Brooklyn. When it was announced that this service was going to be suspended, rents drastically dropped in Williamsburg, Brooklyn, a recently gentrified neighborhood, and many people locked in historically low rents. People were very upset about this sudden closure, and the L service was later not suspended, meaning, ironically, a bunch of people got cheap rents without losing train service.

This is the kind of story that a journalist might write about. Or, you might be someone who locked in that cheap rent, and it’s part of the story of your time living in Williamsburg. In any case, if it’s nonfiction, you’ll want to cite it directly in the text. A journalist might cite people that they interviewed, or a city historian might cite this article and this article . Someone writing creative nonfiction might not need to add a citation, but they would still want to research and communicate the details here so that the reader has context for their story.

To summarize: fiction writers integrate research into their stories, while nonfiction writers cite research to bolster and verify their stories.

Fiction vs. Nonfiction: How Themes are Explored

Theme refers to the overarching ideas presented and explored throughout the story.

Fiction writers explore themes implicitly; for them, the theme of a story is rarely stated. If, for example, the theme of a story is “justice,” then the fiction writer might explore who receives justice, who doesn’t, and how that justice (or lack thereof) is doled out. However, the fiction writer will not say “this character did not receive justice” explicitly—that’s for the reader to understand and form their own opinion about.

Nonfiction writers typically state their themes more openly. In a memoir or essay, the writer might explore why justice was or was not given to them, what factors went into that decision, and what it means to live a life after being (or not being) dispensed justice.

Some nonfiction writers might explore themes without stating them, or even without realizing they’re exploring them. But, because the nonfiction writer wants to convey what it was like to be the subject of the story, they will inevitably explore, and therefore openly state, the deeper parts of the story itself. This includes the author’s emotions, background, external circumstances, and the themes and conclusions that they drew from their experiences.

Similarities Between Fiction and Nonfiction

Despite the above differences, fiction and nonfiction have many similarities, too. In brief, these similarities include:

- The interplay of plot, characters, and settings to explore themes and ideas. While the people of nonfiction stories might not be considered “characters,” they are people presented in a certain way, and with a certain intent, on the page.

- Utilizing prose to tell a story. Fiction and nonfiction writers can both experiment with this: novelists have included poetry in their stories, and essayists, particularly lyric essayists and hermit crab essayists, often play with the prose form.

- The desire to entertain, inform, enlighten, challenge, and/or move the reader.

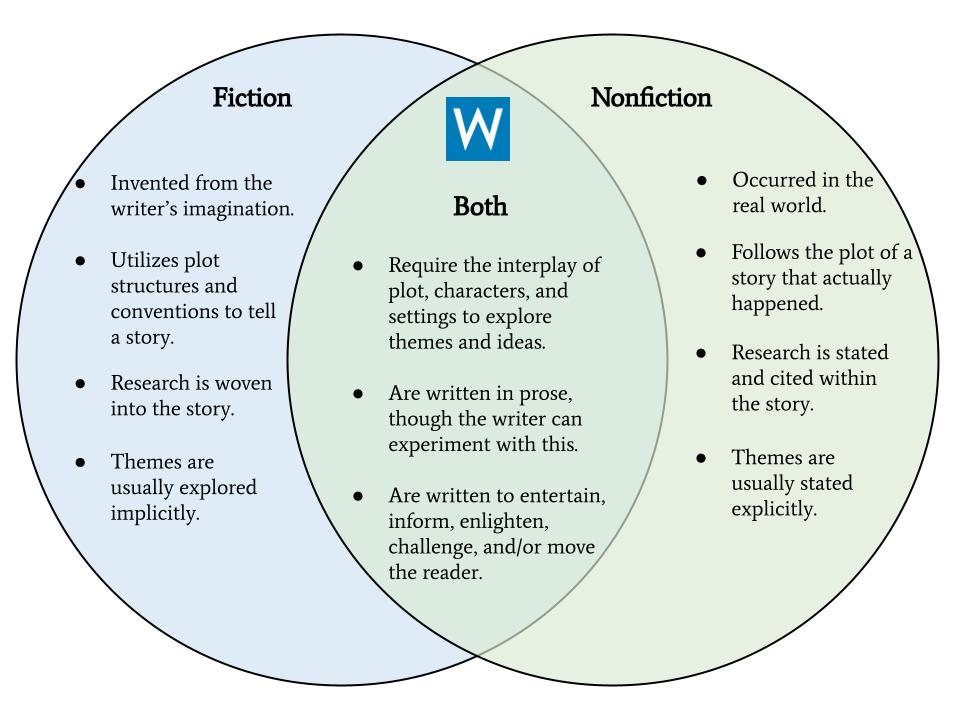

Fiction vs. Nonfiction Venn Diagram

What is the difference between fiction and nonfiction? The below Venn Diagram summarizes what’s similar and different about the two genres. Virtually all things in the world of literature have exceptions, so while the below is not true 100% of the time, it’s a good place to start teasing out the difference between fiction and nonfiction.

| Invented from the writer’s imagination. | Occurred in the real world. | Require the interplay of plot, characters, and settings to explore themes and ideas. |

| Utilizes plot structures and conventions to tell a story. | Follows the plot of a story that actually happened. | Are written in prose, though the writer can experiment with this. |

| Research is woven into the story. | Research is stated and cited within the story. | Are written to entertain, inform, enlighten, challenge, and/or move the reader. |

| Themes are usually explored implicitly. | Themes are usually stated explicitly. |

The Role of “Truth” in Fiction and Nonfiction

The primary difference between fiction and nonfiction is whether or not the story happened in the real world. Yet, we’ve already mentioned three example genres in which fact and fiction can coexist peacefully. So, how much does “truth” matter in fiction vs. nonfiction?

Certainly, most works of nonfiction must be entirely factual. Memoirs, biographies, autobiographies, scholarly works, books about history, and journalism must all adhere to what actually transpired in the real world. When works of nonfiction fabricate details, someone is bound to figure that out eventually, and the ensuing scandal probably isn’t worth it.

At the same time, there’s something to be said about “truth” as a multifaceted concept. One person’s truth can be different than another’s; two people can both have honest, differing interpretations about the exact same event. What matters more than truth, if anything, is honesty.

When memoirists publish their work as memoirs, they assert to the reader that what transpired in the text actually occurred in real life. (So, publishing a memoir about wandering Nazi-torn Europe and being adopted by wolves would not be true or honest, even if it’s a potent metaphor for how the author felt.)

Yet, a memoirist might include information in the novel that’s controversial, in dispute, or otherwise not verifiably true. Does that mean the author lied to their reader?

It really depends on the writer and what they wrote. Consider a few things:

- Emotional truth is sometimes at odds with factual truth. That’s not to say you should invent a metaphor and claim it actually happened. But, the brain works in weird ways, makes odd associations, and reacts to the truth strangely. As a result, your brain might distort memories to make an intense emotion make sense. What the writer conveys to the reader is still an accurate portrayal of how they experienced something, even though their memory of the event itself has been skewed..

- Relatedly, memory is fallible. Unless you have an eidetic memory, you will inevitably forget, distort, or invent details in the memories you set on the page. Research on flashbulb memories proves that none of us remember exactly how we experience our own lives. But, often, the details we do invent have a profound psychological importance, and can still provide moving imagery and description to the story.

- All writing, particularly literature, requires some form of invention . What we mean by this is, real life is far, far messier than literature. In literature, we use plot as a way of organizing a story, and within that story, the details of settings and characters are carefully chosen to explore broader themes and ideas. This is true for both fiction and nonfiction. By asserting these craft elements into retellings of reality, we inevitably neglect certain details, or insert our biases and prejudices into the ways we frame a story. This isn’t to say we shouldn’t strive for the truth—we should—but it is to say that the entire truth may never be properly conveyed. Again, honesty matters more.

Why bring this up? Because all creative nonfiction is an exploration of the truth. And, as all writers know, the truth is far, far messier than fiction. Few truths are absolute. As such, an author’s integrity and dedication to honesty matters much more.

As for fiction, the events of the story are usually fabricated—though writers always pull details from their own lived experiences. Dostoevsky named characters after his children; Steinbeck set the majority of his stories in Central California, where he grew up; Murakami’s novels frequently feature jazz, classical music, baseball, cats, and other things of intimate importance to his life. Ruth Ozeki’s novel A Tale for the Time Being involves characters Ruth and Oliver, named after the author and her husband. The fictional characters have similar traits to the real life Ruth and Oliver.

Sometimes, a work of fiction is rooted in nonfiction, with only some elements added or fabricated. For example, our instructor Barbara Henning ’s novel Thirty Miles to Rosebud is semi-autobiographical.

And, of course, many works of fiction involve completely fictitious elements, especially in genres like fantasy, science fiction, and horror. Even for those genres, however, fiction should still try to arrive at some fundamental truth. Good fiction will inevitably (though not intentionally) teach the reader something about themselves, about others, and/or about the world around them.

Writing Fiction vs. Nonfiction

Many prose writers dabble in both fiction and nonfiction. Which should you write? Are there differences in writing one versus the other? What’s the main difference between fiction and nonfiction writing?

As we’ve discussed, the primary difference between fiction and nonfiction is whether the story occurred in real life. So, the primary difference in writing fiction vs. nonfiction comes down to the concept of “story” itself.

Our instructor Jeff Lyons argues that a story is a metaphor for the human experience . When we follow the plots of characters who must become different people to overcome certain obstacles, we see ourselves and our shared humanities reflected in those stories. To achieve this metaphor, the author must follow certain plot structures. Even in literary fiction, which often breaks the rules of plot structure, the plot must organize and enhance the story that’s being told, since plot is always what develops from the decisions that characters make.

Nonfiction, particularly creative nonfiction, also follows stories of adversity. In fact, most memoir publishers prefer to sell books about people overcoming adversity—feelgood stories sell better than ones that end on a low note. Yet, these stories aren’t metaphors, they actually happened. And, the author isn’t trying to follow a plot structure, the author is trying to organize the story details into a plot that people can follow.

And, other types of nonfiction are less concerned about plot, and more concerned about sharing information. Book length projects might have a plot, but many scholarly works and periodicals don’t need a plot, and many works of journalism follow the Inverted Pyramid . (There are, always, exceptions to these generalities.)

To summarize: Writing fiction involves crafting a story to create metaphors for the human experience. Writing nonfiction involves organizing factual information into a story that readers will best understand.

Outside of these differences, fiction and nonfiction typically utilize the same elements, at least in varying degrees. They both have characters, storylines, and themes, they both benefit from the tactics of stylish writing , and they both seek to inform, move, and captivate their readers.

Write Fiction and Nonfiction at Writers.com

Explore the distinction between fiction vs. nonfiction (and everything in between!) at Writers.com. Our fiction writing and nonfiction writing classes will help you discover your story and write it stylishly.

Sean Glatch

Leave a comment cancel reply.

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Fiction vs. nonfiction?

Nonfiction writing recounts real experiences, people, and periods. Fiction writing involves imaginary people, places, or periods, but it may incorporate story elements that mimic reality.

Your writing, at its best

Compose bold, clear, mistake-free, writing with Grammarly's AI-powered writing assistant

What is the difference between fiction and nonfiction ?

The terms fiction and nonfiction represent two types of literary genres, and they’re useful for distinguishing factual stories from imaginary ones. Fiction and nonfiction writing stand apart from other literary genres ( i.e., drama and poetry ) because they possess opposite conventions: reality vs. imagination.

What is fiction ?

Fiction is any type of writing that introduces an intricate plot, characters, and narratives that an author invents with their imagination. The word fiction is synonymous with terms like “ fable ,” “ figment ,” or “ fabrication ,” and each of these words has a collective meaning: falsehoods, inventions, and lies.

Not all fiction is entirely made-up, though. Historical fiction, for example, features periods with real events or people, but with an invented storyline. Additionally, science fiction novels function around real scientific theories, but the overall story is untrue.

What is nonfiction ?

Nonfiction is any writing that represents factual accounts on past or current events. Authors of nonfiction may write subjectively or objectively, but the overall content of their story is not invented (Murfin 340).

Works of nonfiction are not limited to traditional books, either. Additional examples of nonfiction include:

- Instruction manuals

- Safety pamphlets

- Journalism

- Recipes

- Medical charts

Comparing fiction and nonfiction texts

Outside of reality vs. imagination, nonfiction and fiction writing possess several typical features.

Fictional text features:

- Imaginary characters, settings, or periods

- A subjective narrative

- Novels, novellas, and short stories

- Literary fiction vs. genre fiction ( e.g., sci-fi, romance, mystery )

Nonfiction text features:

- Real people, events, and periods

- An authoritative narrative

- Autobiographies, letters, journals, essays, etc .

- Venn diagrams, anchor charts, mini-lessons, extension activities

- Index, citations, and bibliographies

- Academic/peer-reviewed publishers

What does fiction and nonfiction have in common?

Oftentimes, an elaborate work of fiction has more in common with nonfiction than a simple fairy tale or children’s book. Examples of shared traits include:

- Major literary publishers ( e.g., Hachette Books and HarperCollins )

- Photographic and illustrated book covers

- Stylistic elements such as an index, glossary, or citations

- Themes involving history, mythology, and science

- Creative prose narratives

Prose narratives of fiction vs. nonfiction

According to The Bedford Glossary of Critical and Literary Terms , we can narrowly distinguish fiction from nonfiction through the use of “prose narratives,” a term that refers to an author’s storytelling form.

For works of fiction , authors typically use prose narratives such as the novel , novella , or short story . But for nonfiction books, prose narratives take the form of biographies , expository , letters , essays, and more.

Prose narratives of fiction

A novel is a long, fictional story that involves several characters with an established motivation, different locations, and an intricate plot. Examples of novels include:

- The Great Gatsby by F. Scott Fitzgerald

- Beloved by Tony Morrison

A novel is not the same as a novella , which is a shorter fictional account that ranges between 50-100 pages long. You’ve likely heard of novellas such as:

- Heart of Darkness by Joseph Conrad

- Animal Farm by George Orwell

Lastly, the short story normally contains 1,000-10,000 words and focuses on one event or length of time, such as:

- The Cask of Amontillado by Edgar Allen Poe

- The Story of an Hour by Kate Chopin

Prose narratives of nonfiction

Since nonfiction represents real people, experiences, or events, the most common prose narratives of nonfiction include:

- Biographies

- Autobiographies

- Journals

- Essays

- Informational texts

Biographies and autobiographies

A biography is written about another person, while an autobiography’s author tells the story of their own life. Popular biographies include:

- Into the Wild by Jon Krakauer

- Steve Jobs by Walter Isaacson

The difference between the two modes of nonfiction is further illustrated with autobiographies such as:

- Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass by Frederick Douglass

- I Am Malala: The Girl Who Stood up for Education and Was Shot by Malala Yousafzai

Journals and letters

Journals , diaries , and letters provide a glimpse into someone’s life at a particular moment. Diaries and letters are great resources for historical contexts, and especially for periods involving war or political scandals.

Journal and letters examples:

- The Diary of a Young Girl by Anne Frank

- Ever Yours: The Essential Letters by Vincent van Gogh

Essay writing

By definition, an essay is a short piece of writing that explores a specific subject, such as philosophy, science, or current events. We read essays within magazines, websites, scholarly journals, or through a published collection of essays.

Essay examples:

- Consider the Lobster by David Foster Wallace

- The Source of Self-Regard by Toni Morrison

Informational texts

Informational texts present clear, objective facts about a particular subject, and often take the form of periodicals, news articles, textbooks, printables, or instruction manuals. The difference between informational texts and biographical writing is that biographies possess a range of subjectivity toward a topic, while informational writing is purely educational.

Publishers of informational texts also tailor their writing toward an audience’s reading comprehension. For instance, instructions for first-grade reading levels use different vocabularies than a textbook for college students. The key similarity is that informational writing is clear and educational.

Genres of fiction vs. nonfiction

The French term genre means “kind” or “type,” and genres organize different styles, forms, or subjects of literature. Some sources believe fiction is categorized by genre fiction and literary fiction , while others believe that literary fiction is a subgenre of fiction itself. The same arguments exist within nonfiction genres, except nonfiction is organized by subject matter or writing style.

Whichever way you look at it, all nonfiction and fiction have distinct genres and subgenres that overlap, and there’s no single way to categorize literature without spurring controversy. If you’re ever doubtful about a particular book, try checking the publisher’s website.

What is literary fiction ?

If we stick to the dry characteristics of literary fiction , we can define it as any writing that produces an underlying commentary on the human condition. More specifically, literary fiction often involves a metaphorical , poetic narrative or critique around topics such as war, gender, race, sex, economy, or political ideologies.

Literary fiction examples:

- Quicksand by Nella Larsen

- The Unbearable Lightness of Being by Milan Kundera

- The Sellout by Paul Beatty

What is genre fiction ?

Broadly speaking, genre fiction (or popular fiction ) is any writing with a specific theme and the author’s marketability toward a particular audience (aka, the novel is likely a part of a book series). The most common genres of “ genre fiction ” include:

- Science Fiction

- Suspense/Thriller

Crime fiction and mystery

Crime fiction and mystery novels focus on the motivation of police, detectives, or criminals during an investigation. Four major subgenres of crime fiction and mystery include detective novels, cozy mysteries, caper stories, and police procedurals.

Crime fiction and mystery examples:

- The Godfather by Mario Puzo

- The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo by Steig Larsson

The fantasy genre traditionally occurs in medieval-esque settings and often includes mythical creatures such as wizards, elves, and dragons.

Fantasy examples:

- The Hobbit by J.R.R. Tolkein

- A Game of Thrones by George R.R. Martin

The romance genre features stories about romantic relationships with a focus on intimate details. Romance themes often involve betrayal or heroism and elements of sensuality, idealism, morality, and desire.

Romance examples:

- Dead Until Dark by Charlaine Harris

- Fifty Shades of Grey by E.L. James

Science fiction

Science fiction is one of the largest growing genres because it encompasses several subgenres, such as dystopian, apocalyptic, superhero, or space travel themes. All sci-fi novels incorporate real or imagined scientific concepts within the past, future, or a different dimension of time.

Science fiction examples:

- Parable of the Sower by Octavia E. Butler

- The Left Hand of Darkness by Ursula K. Le Guin

Suspense and horror

Sometimes described as two separate genres, suspense and horror writing focuses on the pursuit and escape of a main character or villain. Suspense writing uses cliffhangers to “grip” readers, but we can distinguish the horror genre through supernatural, demonic, or occult themes.

Suspense and horror examples:

- The Silence of the Lambs by Thomas Harris

- The Shining by Stephen King

Genres of nonfiction

Finally, we meet again in the nonfiction section. When it comes to nonfiction literature, the most common genres include:

- Autobiography/Biography (see “prose narratives” )

Narrative nonfiction

A memoir recounts the memories and experiences for a specific timeline in an author’s life. But unlike an autobiography, a memoir is less chronological and depends on memories and emotions rather than fact-checked research.

Memoir examples:

- Wild by Cheryl Strayed

- When Breath Becomes Air by Paul Kalanithi

Self-help writing focuses on delivering a lesson plan for self-improvement. Authors of self-help books describe experiences like a memoir, but the overall purpose is to teach readers a skill that the author possesses.

Self-help examples:

- How to Win Friends and Influence People by Dale Carnegie

- The Power of Now by Eckhart Tolle

The expository genre introduces or “ exposes ,” a complex subject to readers in an understandable manner. Expository books often take the form of children’s books to provide a clear, educational summary on topics such as history and science.

Examples of adult vs. children’s expository books include:

- Death by Black Hole by Neil deGrasse Tyson

- A Black Hole is Not a Hole by Carolyn Cinami Decristofano

Narrative nonfiction (or “ creative nonfiction ”) tells a true story in the form of literary fiction. In this case, the author presents an autobiography or biography with an emphasis on storytelling over chronology.

The line between creative nonfiction and literary fiction is thin when the narrative’s presentation is too subjective, and when specific facts are omitted or exaggerated. Literary scholars refer to such works as “ faction ,” a portmanteau word for writing that blurs the line between fiction and nonfiction (Murfin 177).

Narrative nonfiction examples:

- In Cold Blood by Truman Capote

- The Devil in the White City by Erik Larson

Additional resources for nonfiction vs. fiction ?

Understanding the elements of fiction vs. nonfiction writing is a common core standard for language arts (ELA) programs. If you’re looking to learn specific forms of fiction and nonfiction writing, The Word Counter provides additional articles, such as:

- Transition Words: How, When, and Why to Use Them

- What Are the Most Cringe-Worthy English Grammar Mistakes?

- Italics and Underlining: Titles of Books

Test Yourself!

Before you visit your next writing workshop, class discussion, or literacy center, test how well you understand the difference between fiction and nonfiction with the following multiple-choice questions (no peeking into Google!)

- True or false: An author’s imagination does not invent nonfiction writing. a. True b. False

- Which term is synonymous with fiction? a. Fact b. Fable c. Reality d. None of the above

- Which is a type of nonfiction writing? a. Novels b. Memoirs c. Novellas d. Short stories

- Which is not a trait of literary fiction? a. Underlying commentary on the human condition b. Poetic narrative c. Social and political commentary d. None of the above

- Which genre of nonfiction is the closest to literary fiction? a. Memoirs b. Expository c. Narrative nonfiction d. Self-help

Photo credits:

[1] Photo by Suad Kamardeen on Unsplash [2] Photo by Jonathan J. Castellon on Unsplash

- “ Essay .” Lexico , Oxford University Press, 2020.

- “ Fiction .” The Merriam-Webster.com Dictionary, Merriam-Webster Inc., 2020.

- MasterClass. “ What Is the Mystery Genre? Learn About Mystery and Crime Fiction, Plus 6 Tips for Writing a Mystery Novel .” MasterClass , 15 Aug 2019.

- Mazzeo, T.J. “ Writing Creative Nonfiction .” The Great Courses , 2012, pp.4.

- Murfin, R., Supryia M. Ray. “ The Bedford Glossary of Critical and Literary Terms .” Third Ed, Bedford/St. Martins , 2009, pp. 177-340.

- “ Nonfiction .” Lexico , Oxford University Press, 2020.World Heritage Encyclopedia. “ List of Literary Genres .” World Library Foundation , 2020.

Alanna Madden

Alanna Madden is a freelance writer and editor from Portland, Oregon. Alanna specializes in data and news reporting and enjoys writing about art, culture, and STEM-related topics. I can be found on Linkedin .

Recent Posts

Allude vs. Elude?

Bad vs. badly?

Labor vs. labour?

Adaptor vs. adapter?

Fiction vs. Nonfiction: Literature Types (Compared)

- by Team Experts

- July 2, 2023 July 3, 2023

Discover the surprising differences between fiction and nonfiction literature types in this eye-opening comparison.

| Step | Action | Novel Insight | Risk Factors |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Define | refer to the different categories of written works that are classified based on their content, , and purpose. | None |

| 2 | Compare and | and are two major literature types that differ in their and content. | None |

| 3 | Define | Narrative style refers to the way a story is told, including the , , and used. | None |

| 4 | Define | is a type of nonfiction that presents information and events that are based on and . | None |

| 5 | Define | are a type of fiction that presents events and that are not based on or people. | None |

| 6 | Define real-life events | Real-life events are a type of nonfiction that presents events and information that are based on actual occurrences. | None |

| 7 | Define | is a type of fiction that allows the author to use their to create , events, and . | None |

| 8 | Define | are a type of nonfiction that presents information and about a particular topic. | None |

| 9 | Define | are categories of that are defined by their content, , and purpose, such as romance, , or science fiction. | None |

In conclusion, literature types are an essential aspect of written works that help readers understand the content, style, and purpose of a particular piece. Fiction and nonfiction are two major literature types that differ in their narrative style and content. Fiction includes imaginary stories and creative writing, while nonfiction includes fact-based writing and informational texts. Understanding these literature types and their differences can help readers choose the right book for their needs.

What are the Different Literary Types?

Narrative style in fiction and nonfiction writing, real-life events in nonfiction vs creative writing in fiction, informational texts: understanding their role in literature, common mistakes and misconceptions.

| Step | Action | Novel Insight | Risk Factors |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Identify the different literary types | There are various literary types, including , , , , , , , , , , , , , and | None |

| 2 | Define | Poetry is a of that uses to evoke , paint vivid , and convey complex ideas in a condensed and imaginative way | Poetry can be difficult to understand for some readers |

| 3 | Define | Drama is a type of that is written to be performed on stage or screen, and it often involves , , and between | Drama can be challenging to write and produce |

| 4 | Define | Prose is a of written or spoken that is not structured into , and it is often used for , , and other forms of non- writing | Prose can be less and imaginative than poetry |

| 5 | Define | A memoir is a type of that focuses on a specific period or in the author’s life, and it often includes personal and insights | Memoirs can be biased or subjective |

| 6 | Define | An autobiography is a type of writing that tells the story of the author’s life, often from birth to the present day, and it can include , , and insights | Autobiographies can be self-indulgent or overly detailed |

| 7 | Define | A biography is a type of writing that tells the story of someone else’s life, often with a focus on their achievements, struggles, and on society | Biographies can be influenced by the author’s biases or limited by the available information |

| 8 | Define | An essay is a type of writing that presents an argument, , or personal reflection on a specific topic, often in a structured and formal way | Essays can be challenging to write and require strong |

| 9 | Define | Satire is a type of writing that uses , , and to criticize or human vices, follies, and shortcomings | Satire can be offensive or misunderstood by some readers |

| 10 | Define | A fable is a type of story that uses animals, plants, or inanimate objects to teach a or convey a universal about | Fables can be or predictable |

| 11 | Define | Mythology is a type of literature that explores the origins, beliefs, and of a particular culture or society, often through the use of gods, goddesses, and | Mythology can be complex and difficult to understand for some readers |

| 12 | Define | A legend is a type of story that is based on historical or mythical events, often with a focus on heroic or | Legends can be exaggerated or distorted over time |

| 13 | Define | A folktale is a type of story that is passed down orally from generation to generation, often with a focus on , beliefs, and | Folktales can vary widely in and content |

| 14 | Define | An epic is a type of long-form that tells the story of a ‘s journey, often with a focus on of courage, honor, and destiny | Epics can be challenging to read and require a significant time commitment |

| 15 | Define | Tragedy is a type of drama that explores the downfall of a or heroine, often with a focus on themes of , , and | Tragedies can be emotionally intense and difficult to watch or read |

| Step | Action | Novel Insight | Risk Factors |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Identify the | and writing have different . | Misunderstanding the between the two can lead to and ineffective writing. |

| 2 | uses to develop the personalities of the . | writing may use characterization to describe real people, but it is not as prevalent as in . | |

| 3 | uses to reveal traits and advance the . | Nonfiction writing may use dialogue to provide or quotes from real people, but it is not as common as in fiction. | |

| 4 | Fiction writing uses a structured to create and . | Nonfiction writing may use a structured plot, but it is not as necessary as in fiction. | |

| 5 | Fiction writing uses to create vivid and . | Nonfiction writing may use imagery, but it is not as prevalent as in fiction. | |

| 6 | Fiction writing uses to convey the author’s towards the subject matter. | Nonfiction writing may use tone, but it is not as subjective as in fiction. | |

| 7 | Fiction writing uses to create an in the reader. | Nonfiction writing may use mood, but it is not as prevalent as in fiction. | |

| 8 | Fiction writing uses to create a sense of place and . | Nonfiction writing may use setting, but it is not as necessary as in fiction. | |

| 9 | Fiction writing uses to convey a or . | Nonfiction writing may use theme, but it is not as prevalent as in fiction. | |

| 10 | Fiction writing uses to hint at future events. | Nonfiction writing may use foreshadowing, but it is not as prevalent as in fiction. | |

| 11 | Fiction writing uses to provide or . | Nonfiction writing may use flashback, but it is not as prevalent as in fiction. | |

| 12 | Fiction writing uses to represent abstract ideas or concepts. | Nonfiction writing may use symbolism, but it is not as prevalent as in fiction. | |

| 13 | Fiction writing uses to create a between what is expected and what actually happens. | Nonfiction writing may use irony, but it is not as prevalent as in fiction. | |

| 14 | Fiction writing uses to create and advance the plot. | Nonfiction writing may use conflict, but it is not as prevalent as in fiction. | |

| 15 | Fiction writing uses to create a turning point in the story. | Nonfiction writing may use climax, but it is not as prevalent as in fiction. |

Overall, understanding the differences in narrative style between fiction and nonfiction writing is crucial for effective storytelling . While some elements may overlap, such as plot structure and conflict, the use of characterization, dialogue, imagery, tone, mood, setting, theme, foreshadowing, flashback, symbolism, irony, and climax differ greatly between the two styles . It is important to consider these elements when choosing a narrative style and to use them effectively to engage and captivate the reader.

| Step | Action | Novel Insight | Risk Factors |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Identify the purpose of the writing | aims to inform and educate readers about , while aims to entertain and engage readers through | may be limited by the availability of information, while may require more and creativity |

| 2 | Determine the type of writing | Nonfiction can take the of , , , historical fiction, , , literary , personal , expository writing, and -based writing, while fiction can be imaginative | Nonfiction may require more and -checking, while fiction may require more attention to and |

| 3 | Gather information | Nonfiction requires accurate and reliable information about , while fiction requires creative ideas and imaginative | Nonfiction may require more time and effort to gather information, while fiction may require more time and effort to develop and |

| 4 | Determine the level of | Nonfiction should be based on real-life events and should not be overly fictionalized, while fiction can be completely made up or based on real-life events with varying of | Nonfiction may risk losing if it is overly fictionalized, while fiction may risk losing if it is too closely based on real-life events |

| 5 | Use | Fiction can use literary devices such as , , and to enhance the , while nonfiction can use literary devices such as anecdotes and to make the writing more engaging | Fiction may risk becoming too abstract or confusing if literary devices are overused, while nonfiction may risk becoming too dry or boring if literary devices are not used effectively |

| 6 | Edit and revise | Both nonfiction and fiction require and to improve the , , and effectiveness of the writing | Nonfiction may require more and to ensure accuracy and , while fiction may require more editing and revision to ensure and |

Overall, the key difference between real-life events in nonfiction and creative writing in fiction is the purpose of the writing and the level of fictionalization. Nonfiction aims to inform and educate readers about real-life events, while fiction aims to entertain and engage readers through creative writing. Nonfiction requires accurate and reliable information about real-life events, while fiction requires creative ideas and imaginative storytelling. Nonfiction should be based on real-life events and should not be overly fictionalized, while fiction can be completely made up or based on real-life events with varying degrees of fictionalization. Both nonfiction and fiction require editing and revision to improve the clarity, coherence, and effectiveness of the writing.

| Step | Action | Novel Insight | Risk Factors |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Identify the purpose of the . | are written to inform, educate, or explain a topic to the reader. | The reader may not find the topic interesting or relevant to their needs. |

| 2 | Determine the type of informational text. | There are various types of informational texts, including expository writing, , , , , , , , , and . | The reader may not be familiar with the different types of informational texts. |

| 3 | Analyze the of the informational text. | Informational texts are structured differently from , with a focus on , , and evidence. | The reader may find the of the text too dry or boring. |

| 4 | Evaluate the of the information presented. | Informational texts should be based on reliable sources and accurate information. | The reader may encounter biased or false information. |

| 5 | Consider the for the informational text. | Informational texts are written for a specific , such as students, professionals, or general readers. | The reader may not be the intended audience for the text. |

| 6 | Reflect on the of the informational text. | Informational texts can broaden the reader’s knowledge, challenge their beliefs, or inspire them to take action. | The reader may not be open to new ideas or . |

Overall, understanding the role of informational texts in literature can provide readers with valuable knowledge and insights on various topics. However, it is important to approach these texts with a critical eye and consider the potential risks of biased or false information. By analyzing the purpose, type, structure, credibility , audience, and impact of informational texts, readers can gain a deeper understanding of the world around them.

| Mistake/Misconception | Correct Viewpoint |

|---|---|

| is not based on reality. | While may be a work of , it can still be grounded in reality and draw inspiration from or people. |

| is always factual and objective. | can also have biases, opinions, and subjective depending on the author’s . It is important to critically evaluate nonfiction sources as well. |

| Fiction is only for entertainment purposes. | While entertainment may be one purpose of fiction, it can also serve to educate, inspire , explore complex and issues, or offer . |

| Nonfiction is always informative and . | While nonfiction may aim to inform or educate readers about a particular topic or event, it can also simply tell a story without necessarily providing new information or insights. |

| Fiction cannot teach us anything valuable about life or . | Many works of fiction offer profound insights into the human condition and provide opportunities for and personal growth through their exploration of such as love, , , etc.. |

| books are boring compared to fictional stories. | books cover various topics that could interest different individuals like science politics among others hence they are not boring but rather informative. |

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

Introduction

“We sailed out of Miles River for Baltimore on a Saturday morning. I remember only the day of the week, for at that time I had no knowledge of the days of the month, nor the months of the year. On setting sail, I walked aft, and gave to Colonel Lloyd’s plantation what I hoped would be my last look. I then placed myself in the bows of the sloop, and there spent the remainder of the day in looking ahead, interesting myself in what was in the distance rather than in things near by or behind.”

When you read the excerpt above, how do you categorize it? In other words, do you identify it as fiction or nonfiction? It can be difficult to discern the difference, especially with narrative nonfiction. The excerpt above comes from “Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, An American Slave,” one of the most renowned memoirs of the nineteenth-century. However, if you identified elements that seem familiar from your readings of fiction, you would not be misguided. Creative nonfiction, like fiction, features a narrator, scenes, setting, and plot. What distinguishes nonfiction from fact? Ultimately, little more than that the writer purports to be relaying a true story.

Nonfiction vs. Fiction

Is all fiction literature is all nonfiction literature.

Fiction refers to literature created from the imagination. Mysteries, science fiction, romance, fantasy, chick lit, crime thrillers are all fiction genres. Whether or not all of these genres should be considered “literature” is a matter of opinion. Some of these fiction genres are taught in literature classrooms and some are not usually taught, considered more to be reading for entertainment. Works often taught in literature classrooms are referred to as “literary fiction” including classics by Dickens, Austen, Twain, and Poe, for example.

Like fiction, non-fiction also has a sub-genre called “literary nonfiction” that refers to literature based on fact but written in creative way, making it as enjoyable to read as fiction. Of course there are MANY other types of nonfiction such as cookbooks, fitness articles, crafting manuals, etc. which are not “literature,” meaning not the types of works we would study in a literature classroom. However, you may not be aware of the many types of nonfiction we would study, such as biography, memoir or autobiography, essays, speeches, and humor. Of these literary nonfiction genres, they can be long like a book or series of books or short like an essay or journal entry. Some examples of these you are already familiar with, like The Diary of Anne Frank or Angela’s Ashes by Frank McCourt. These works of literary nonfiction have character, setting, plot, conflict, figurative language, and theme just like literary fiction.

Clarification: The test of categorizing a work between fiction and nonfiction is not whether there is proof the story is true, but whether it CLAIMS to be true. For example, someone writing a first hand account of being abducted by aliens would be classified in the nonfiction section, meaning the author claims it really happened. Further, a story in which imaginary characters are set into real historical events is still classified as fiction.

Introduction to Literature. Licensed under CC BY SA 4.0 https://courses.lumenlearning.com/suny-introliterature/chapter/introduction-to-nonfiction/

“Introduction to Creative Nonfiction.” Licensed under Standard Youtube License https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=GPOWTIHOln8

There are many types of fiction and there are many types of nonfiction. Sometimes, distinguishing between the genres is easy. For example, it would be difficult to confuse a mystery novel with a cookbook or a romance novel with an encyclopedia. Where the differentiation becomes more difficult is in instances of creative nonfiction that uses narrative. This is sometimes called narrative nonfiction.

Narrative nonfiction has a lot in common with literary fiction. Literary fiction simply refers to literature, those works that do not ascribe to be part of a sub-genre such as mystery or crime. You’re probably familiar with many works of literature or literary fiction. Novels such as Pride and Prejudice, Gulliver’s Travels, and The Catcher in the Rye are all examples of literary fiction.

What these texts have in common with nonfiction is the usage of key literary elements. These elements—a narrator, setting, characterization, plot, and theme—help nonfiction writers create memoirs, personal essays, autobiographies, and biographies that are just as captivating as their fictional counterparts. What might make them even more compelling than some fiction is, of course, the fact that purport to represent lived life.

ENG134 – Literary Genres Copyright © by The American Women's College and Jessica Egan is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, generate accurate citations for free.

- Knowledge Base

- How to write a narrative essay | Example & tips

How to Write a Narrative Essay | Example & Tips

Published on July 24, 2020 by Jack Caulfield . Revised on July 23, 2023.

A narrative essay tells a story. In most cases, this is a story about a personal experience you had. This type of essay , along with the descriptive essay , allows you to get personal and creative, unlike most academic writing .

Instantly correct all language mistakes in your text

Upload your document to correct all your mistakes in minutes

Table of contents

What is a narrative essay for, choosing a topic, interactive example of a narrative essay, other interesting articles, frequently asked questions about narrative essays.

When assigned a narrative essay, you might find yourself wondering: Why does my teacher want to hear this story? Topics for narrative essays can range from the important to the trivial. Usually the point is not so much the story itself, but the way you tell it.

A narrative essay is a way of testing your ability to tell a story in a clear and interesting way. You’re expected to think about where your story begins and ends, and how to convey it with eye-catching language and a satisfying pace.

These skills are quite different from those needed for formal academic writing. For instance, in a narrative essay the use of the first person (“I”) is encouraged, as is the use of figurative language, dialogue, and suspense.

Here's why students love Scribbr's proofreading services

Discover proofreading & editing

Narrative essay assignments vary widely in the amount of direction you’re given about your topic. You may be assigned quite a specific topic or choice of topics to work with.

- Write a story about your first day of school.

- Write a story about your favorite holiday destination.

You may also be given prompts that leave you a much wider choice of topic.

- Write about an experience where you learned something about yourself.

- Write about an achievement you are proud of. What did you accomplish, and how?

In these cases, you might have to think harder to decide what story you want to tell. The best kind of story for a narrative essay is one you can use to talk about a particular theme or lesson, or that takes a surprising turn somewhere along the way.

For example, a trip where everything went according to plan makes for a less interesting story than one where something unexpected happened that you then had to respond to. Choose an experience that might surprise the reader or teach them something.

Narrative essays in college applications

When applying for college , you might be asked to write a narrative essay that expresses something about your personal qualities.

For example, this application prompt from Common App requires you to respond with a narrative essay.

In this context, choose a story that is not only interesting but also expresses the qualities the prompt is looking for—here, resilience and the ability to learn from failure—and frame the story in a way that emphasizes these qualities.

An example of a short narrative essay, responding to the prompt “Write about an experience where you learned something about yourself,” is shown below.

Hover over different parts of the text to see how the structure works.

Since elementary school, I have always favored subjects like science and math over the humanities. My instinct was always to think of these subjects as more solid and serious than classes like English. If there was no right answer, I thought, why bother? But recently I had an experience that taught me my academic interests are more flexible than I had thought: I took my first philosophy class.

Before I entered the classroom, I was skeptical. I waited outside with the other students and wondered what exactly philosophy would involve—I really had no idea. I imagined something pretty abstract: long, stilted conversations pondering the meaning of life. But what I got was something quite different.

A young man in jeans, Mr. Jones—“but you can call me Rob”—was far from the white-haired, buttoned-up old man I had half-expected. And rather than pulling us into pedantic arguments about obscure philosophical points, Rob engaged us on our level. To talk free will, we looked at our own choices. To talk ethics, we looked at dilemmas we had faced ourselves. By the end of class, I’d discovered that questions with no right answer can turn out to be the most interesting ones.

The experience has taught me to look at things a little more “philosophically”—and not just because it was a philosophy class! I learned that if I let go of my preconceptions, I can actually get a lot out of subjects I was previously dismissive of. The class taught me—in more ways than one—to look at things with an open mind.

If you want to know more about AI tools , college essays , or fallacies make sure to check out some of our other articles with explanations and examples or go directly to our tools!

- Ad hominem fallacy

- Post hoc fallacy

- Appeal to authority fallacy

- False cause fallacy

- Sunk cost fallacy

College essays

- Choosing Essay Topic

- Write a College Essay

- Write a Diversity Essay

- College Essay Format & Structure

- Comparing and Contrasting in an Essay

(AI) Tools

- Grammar Checker

- Paraphrasing Tool

- Text Summarizer

- AI Detector

- Plagiarism Checker

- Citation Generator

If you’re not given much guidance on what your narrative essay should be about, consider the context and scope of the assignment. What kind of story is relevant, interesting, and possible to tell within the word count?

The best kind of story for a narrative essay is one you can use to reflect on a particular theme or lesson, or that takes a surprising turn somewhere along the way.

Don’t worry too much if your topic seems unoriginal. The point of a narrative essay is how you tell the story and the point you make with it, not the subject of the story itself.

Narrative essays are usually assigned as writing exercises at high school or in university composition classes. They may also form part of a university application.

When you are prompted to tell a story about your own life or experiences, a narrative essay is usually the right response.

The key difference is that a narrative essay is designed to tell a complete story, while a descriptive essay is meant to convey an intense description of a particular place, object, or concept.

Narrative and descriptive essays both allow you to write more personally and creatively than other kinds of essays , and similar writing skills can apply to both.

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the “Cite this Scribbr article” button to automatically add the citation to our free Citation Generator.

Caulfield, J. (2023, July 23). How to Write a Narrative Essay | Example & Tips. Scribbr. Retrieved August 29, 2024, from https://www.scribbr.com/academic-essay/narrative-essay/

Is this article helpful?

Jack Caulfield

Other students also liked, how to write an expository essay, how to write a descriptive essay | example & tips, how to write your personal statement | strategies & examples, "i thought ai proofreading was useless but..".

I've been using Scribbr for years now and I know it's a service that won't disappoint. It does a good job spotting mistakes”

- Skip to main content

- Skip to primary sidebar

- Skip to footer

Additional menu

The Creative Penn

Writing, self-publishing, book marketing, making a living with your writing

How To Write Narrative Non-Fiction With Matt Hongoltz-Hetling

posted on August 24, 2020

Podcast: Download (Duration: 1:04:14 — 52.2MB)

Subscribe: Spotify | TuneIn | RSS | More

What is narrative non-fiction and how do you write a piece so powerful it is nominated for a Pulitzer? In this interview, Matt Hongoltz-Hetling talks about his process for finding stories worth writing about and how he turns them into award-winning articles.

In the intro, I talk about Spotify (possibly) getting into audiobooks and Amazon (possibly) getting into podcasts as reported on The Hotsheet , and the New Publishing Standard . David Gaughran's How to Sell Books in 2020 ; a college student who used GPT3 to reach the top of Hacker News with an AI-generated blog post [ The Verge ]; and ALLi on Is Copyright Broken? Artificial Intelligence and Author Copyright . Plus, synchronicity in book research, and my personal podcast episode on Druids, Freemasons, and Frankenstein: The Darker Side of Bath, England (where I live!)

Matt Hongoltz-Hetling is a Pulitzer finalist and award-winning investigative journalist. He's also the author of A Libertarian Walks Into a Bear .

You can listen above or on your favorite podcast app or read the notes and links below. Here are the highlights and the full transcript below.

- From writing for pennies an article to writing a Pulitzer – nominated article

- What is narrative non-fiction?

- How does narrative non-fiction differ from fiction?

- Where ideas come from and how to begin forming a story idea

- The necessity of being respectful of the real lives being examined and written about

- Portraying interview subjects with shades of grey

- Turning hours of source material into something coherent

- Finding the balance between story structure and meaning

- Knowing when an idea is appropriate for a book

You can find Matt Hongoltz-Hetling at matt-hongoltzhetling.com and on Twitter @hh_matt

Transcript of Interview with Matt Hongoltz-Hetling

Joanna: Matt Hongoltz-Hetling is a Pulitzer finalist and award-winning investigative journalist. He's also the author of A Libertarian Walks Into a Bear . Welcome, Matt.

Matt: Hey, thanks for having me on, Joanna.

Joanna: It's great to have you on the show.

First up, tell us a bit more about you and how you got into writing.

Matt: I got into writing when I was eight years old and I wrote this amazing book. I don't want to brag, but I wrote this book about an elf that was fighting in a dungeon, and this elf had some items of a magical persuasion and used them to defeat all sorts of monsters. So, that was pretty awesome. And I've been writing stuff ever since.

I grew up knowing that I wanted to write, loving to read, all that. And then my career path never really seemed to go that way. I actually started a student newspaper when I was in college in the hopes that that would be primarily a writing occupation, but I found very quickly that it was more small business skills that were needed.

I was selling advertisements much more so than writing to fill the newspaper sadly. And so, at some point I had just got the pile of rejection slips that I think we're all familiar with. I just didn't really know how to go about getting into the industry.

I was literally writing articles for, like, 25 cents an article, these, like, ‘How do you fix an engine?' or not even an engine, nothing that complicated, but, ‘How do you clean a window?'

Joanna: Content farms.

Matt: Yes, right. Content farms. Yes. Thank you. But I was writing.

My wife encouraged me to submit an article for my local weekly newspaper in a small town in the state of Maine. And that led to me being able to write more articles, still for very small amounts, 30 bucks an article. And that led to me getting a full-time job as a journalist at a weekly newspaper in rural Maine.

And even though that was fantastically exciting for me, I always knew that I wanted to do more. And so, I was always pushing, looking for that next level that would allow me to write more of the stuff that I wanted to write. And so, that led to larger newspapers, and then magazine opportunities, and then magazine opportunities led to a book opportunity. Now, I'm happy that I am just on the cusp of publishing my first book. I'm very excited about that.

Joanna: We're going to get into that in a second, but I just wonder because this is so fascinating.

How many years was it between writing for a content farm to being a Pulitzer finalist?

Matt: That was actually the shortest journey that you can imagine. Within, let's say, two years of my first newspaper article. I wrote the article that led to my highest-profile resume point which was that Pulitzer finalist status. And that article was about substandard housing conditions in the federal Section 8 program. It's federally subsidized housing and it's meant to be kept up to a certain standard, and the article which I wrote with a writing partner demonstrated that it was not and that there were a lot of people at fault.

What really elevated that article, it was a good article and all of that, but what really got it that level of recognition was that it also turned out to be an impactful article. It happened to come at a time when other people were looking at the housing authority for various reasons. It really struck a nerve and our Senator, Republican Susan Collins of Maine, she took a very avid interest in our reporting and was motivated to encourage reforms of the national Section 8 system.

She was in a political position to do that because she held the purse strings for the housing authorities. And so, it happened to have this very disproportionate impact and because it led to a positive change for the Section 8 housing program in the United States.

I think the people in the Pulitzer committee must've loved the idea that this tiny little rural weekly newspaper where we had three reporter desks, one of which was perennially vacant, had managed to write a story that was really relevant to the national scene.

Joanna: Absolutely fascinating. And I hope that encourages people listening who might feel that they're in a place in their writing career where they're not feeling very successful and yet you bootstrapped your way up there to something really impactful, as you say.

We're going to come back to the craft of writing, but let's just define ‘narrative nonfiction.' Your book, A Libertarian Walks Into a Bear , which is a great title.

What is narrative nonfiction and where's the line between that and fiction or straight nonfiction?

Matt: Narrative nonfiction, the way that I think of it is i t's basically just like any other fiction book, or novel, or piece that you might pick up except for the events described in it actually happened .

When I think of the difference, it just seems, to me, to be such a small, tiny little difference between fiction and nonfiction because when you write fiction, you're starting with an infinite number of possible events to write about. And when you're writing nonfiction, you're starting with a universe of events.

You're starting with everything that ever happened in the entire universe. That's the material that you can draw on. It is so close to infinite that really, it's just a method of curation. You're going to select some of these facts and arrange them in an order that will create the same exact experience as a powerful piece of fiction writing.

A narrative piece emphasizes the same things that a fiction story would in terms of there's character arcs, there are transformations, there's setting. We want a climax, we want everything that you would want when you're writing a fiction piece.

Joanna: Interesting. And you said at the beginning that it's a tiny difference between fiction and nonfiction. And I'm like, ‘No, surely, this is the biggest separation.' So, I feel like people would have quite a different view on that, but it's interesting because you said there, ‘a method of curation,' and you select the facts, whereas with fiction, obviously, you make it up.

How can you curate truth in a way that serves your story but doesn't distort what really happened?

Matt: That's an excellent question. And I think you do have to be careful to keep things in perspective.

So, I was thinking, ‘What if I was writing about someone in the aeronautics industry or who was an astronaut or maybe someone else within the industry who is motivated by this idea that people want to,' or yeah, ‘that he would like people to colonize the stars?' That's, I think, a very common sci-fi-type theme, and it's also very apparent in the people who go into those fields.

And so, you might take a set of facts. I would ask that person, ‘What are some of the seminal moments in your career? What were the turning points? What were the important things that shaped you as a person?' And this was just an idea that I had, I would look at the amount of cosmic matter in our atmosphere. So, every time a meteor hits the atmosphere, we know it burns up, dust rains down on the earth and that dust becomes part of us. We breathe it in.

Then I would try to draw a timeline between some natural spike in the amount of cosmic dust in the air that might've gone into our subject's body, and that person's decision to get into aeronautics. So, you maybe get to describe that this fantastic spectacular event of a comet the size of a blue whale entering the atmosphere, burning up, raining dust down on, let's say, North America.

And this aeronautics person is 12 years old at the time, he's thinking about baseball, but then he goes to a museum two weeks later and he's breathing in more cosmic dust on that day than he would on an average day, and then he decides to become an astronaut.

You can paint a very poetic scene with that, but it's also very important that you're not actually suggesting or theorizing that the cosmic dust had anything to do with that person's decision.

It's a way to wax poetically about this character and to maybe access a greater idea which is that we all want to go colonize the stars to some extent. That's a very human thing. It appears in our very earliest writings on both fictional and non-fictional.

And you can talk about this amazing spectacular event, you can talk about this person's decision, and if you do it right, the audience will understand that you've just used this as a jumping-off point to explore some of these bigger concepts and cool narrative opportunities without actually saying in a false way that cosmic dust is what makes us want to go out there. So, I'm just saying that you can arrange those events in a way that gives it life, and vibrancy, and maybe some creativity.

Joanna: I like that example. And you brought up so many things that I'm thinking about there.

First of all is using the individual to highlight the universal. If you wrote a piece about how big the universe is or whatever, that's not narrative nonfiction. That might be one of your how-to articles back in the day. So, you've used someone's experience to highlight something universal.