An official website of the United States government

Official websites use .gov A .gov website belongs to an official government organization in the United States.

Secure .gov websites use HTTPS A lock ( Lock Locked padlock icon ) or https:// means you've safely connected to the .gov website. Share sensitive information only on official, secure websites.

- Publications

- Account settings

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

Interventions to reduce burnout among clinical nurses: systematic review and meta-analysis

Chiyoung cha.

- Author information

- Article notes

- Copyright and License information

Corresponding author.

Received 2022 May 22; Accepted 2023 Jul 4; Collection date 2023.

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ .

Sporadic evidence exists for burnout interventions in terms of types, dosage, duration, and assessment of burnout among clinical nurses. This study aimed to evaluate burnout interventions for clinical nurses. Seven English databases and two Korean databases were searched to retrieve intervention studies on burnout and its dimensions between 2011 and 2020.check Thirty articles were included in the systematic review, 24 of them for meta-analysis. Face-to-face mindfulness group intervention was the most common intervention approach. When burnout was measured as a single concept, interventions were found to alleviate burnout when measured by the ProQoL (n = 8, standardized mean difference [SMD] = − 0.654, confidence interval [CI] = − 1.584, 0.277, p < 0.01, I 2 = 94.8%) and the MBI (n = 5, SMD = − 0.707, CI = − 1.829, 0.414, p < 0.01, I 2 = 87.5%). The meta-analysis of 11 articles that viewed burnout as three dimensions revealed that interventions could reduce emotional exhaustion (SMD = − 0.752, CI = − 1.044, − 0.460, p < 0.01, I 2 = 68.3%) and depersonalization (SMD = − 0.822, CI = − 1.088, − 0.557, p < 0.01, I 2 = 60.0%) but could not improve low personal accomplishment. Clinical nurses' burnout can be alleviated through interventions. Evidence supported reducing emotional exhaustion and depersonalization but did not support low personal accomplishment.

Subject terms: Health services, Occupational health, Health care

Introduction

Burnout, first described by Freudenberger 1 , is a negative condition characterized by the gradual depletion of physical, emotional, and mental energy due to excessive work 2 . Maslach (1976) later conceptualized burnout as a multidimensional syndrome characterized by emotional exhaustion, depersonalization, and diminished personal commitment 3 . Burnout occurs during the maintenance of interpersonal relationships and is most prevalent in the fields of nursing, medicine, and education, which deal directly with many people 3 .

Nursing is an occupation that experiences one of the highest rates of burnout 4 . Nurse burnout is defined as a physical, psychological, emotional, and socially exhausted status caused by unsuccessfully managed job stress and limited social support 5 . The globally pooled prevalence of nurse burnout is 11.2% 6 . However, in other studies classifying burnout symptoms, nurse burnout was as high as 40.0% 7 , 8 . Moreover, nurse burnout in the post-COVID-19 pandemic era has worsened. In a recent study, nurse burnout was as high as 68.0% 9 .

The factors that contribute to burnout are diverse and intricate. Occupational stress is the most influential factor 10 . The causes of nurse burnout were excessive workload; lack of staffing; role conflict; low autonomy; time pressure; interpersonal conflict between patients, guardians, and medical staff; and absence of leadership support 11 . Burnout can have a significant impact on the group and the organization, so prevention and action are required 2 . The impact of nurse burnout is significant in that it not only negatively influences nurses but also patients and healthcare organizations 5 . Nurse burnout is associated with low-quality care, a threat to patient safety 12 , medication error 13 , and an extended patient hospital stay 14 . Nurses who experience burnout have physical symptoms, such as headache, fatigue, hypertension, and musculoskeletal problems 5 , and psychological symptoms, such as depression, sleep disorders, and difficulty concentrating 15 . Exhausted nurses may also experience behavioral disorders that negatively affect their health, such as smoking and drinking alcohol 5 . Nurse burnout might lead to the turnover 16 and a subsequent burden to healthcare organizations 11 .

Nurse burnout has been a frequently investigated topic owing to its high prevalence and detrimental impact. However, systematic reviews and meta-analysis studies were focused on the description of the nurse burnout phenomenon such as the prevalence of nurse burnout 7 , burnout level and risk factors 17 , and burnout-related factors in nurses 18 . Previous systematic reviews or meta-analysis studies that evaluated the effects of burnout programs were limited to mindfulness training 19 and coping strategies 20 . However, various programs, such as yoga, communication skills, stress management, mindfulness, meditation, and cognitive behavioral therapy, were implemented independently or in combination, and the level of evidence varied 21 , 22 . Nurse burnout interventions should be evaluated inclusively to understand their current effectiveness in reducing burnout among nurses. Previously conducted systematic reviews and meta-analyses on burnout interventions inclusively evaluated health professionals, which included nurses and medical doctors as participants 22 , 23 . However, nurses and medical doctors have different job descriptions 24 and different patterns of burnout 25 . Accordingly, to retrieve evidence for nurse burnout programs, the analysis should be refined to interventions specifically designed and implemented for nurses.

Furthermore, burnout has been measured in many ways. Burnout could be measured as a single concept 26 – 28 , though it is often measured as three dimensions based on the International Classification of Disease-11 (ICD-11). The most frequently used measure is the Maslach Burnout Inventory (MBI), which lists three areas of burnout: emotional exhaustion, depersonalization, and low personal accomplishment 23 , 29 . Some studies used the total score of the MBI and others used the three areas of burnout with some variations 30 , 31 . To be inclusive, burnout interventions should be evaluated by including studies that used burnout as a single concept and as three dimensions. Per this understanding, we aimed to analyze burnout interventions for clinical nurses.

This study is a systematic review and meta-analysis study on the effects of burnout reduction programs for clinical nurses. We followed the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA) guideline 32 .

Eligibility criteria

We used the PICO-SD (Population, Interventions, Comparison, Outcome—Study Design) framework to organize our research question: What is the effect of an intervention on reducing burnout among clinical nurses? Detailed information regarding the eligibility criteria is described in Table 1 . We selected articles published between 2011 and 2020 to yield results that reflected the reality of burnout intervention effects.

Eligibility criteria.

Search strategies

Nine search engines were utilized: seven global search engines in English (PubMed, CINAHL, PsycINFO, Scopus, ProQuest Dissertations & Theses (PQDT) Global, EBSCO, and Cochrane Library) and two domestic search engines in Korean (RISS, KISS). The search terms were “nurse*” and “burnout” and a combination of (Nurses OR nurse* OR registered nurse* OR healthcare provider* OR nursing staff OR healthcare worker* OR health care provider* OR health care worker* OR health personnel* OR health professional*) AND (burnout OR burn-out OR burn out) AND (treatment* OR intervention* OR program* OR therapy OR training OR exercise* OR practice* OR mindfulness OR meditation OR massage OR yoga).

Study selection and data extraction

Endnote 20.0 was used to manage retrieved studies and screen the redundant ones. After retrieval of the studies, titles and abstracts were reviewed to remove irrelevant studies. A full-text review of the studies was conducted afterward. Throughout the process, we worked independently and met weekly to discuss the process and select the studies.

Risk-of-bias assessment

To evaluate the risk of bias, we used the Cochrane’s Risk of Bias 2.0 (RoB 2.0) for the randomized controlled trials and Risk of Bias in Non-randomized Studies of Interventions (RoBINS-I) for the quasi-experimental studies. Discrepancies were resolved through discussion. In addition, a funnel plot was utilized to evaluate the possibility of publication bias.

Data synthesis and meta-analysis

For the systematic review, tables were used to classify article contents for descriptive analyses. For the meta-analysis, the R-4.1.1 program for Windows was used. In 16 articles, burnout was measured as a single concept using various instruments, while in 11 articles, burnout was measured as three dimensions: emotional exhaustion, depersonalization, and low personal accomplishment. Meta-analysis was conducted with the fixed effect model and the random effect model with 95% confidence interval, pooled mean differences, and weight of each article for each meta-analysis. The heterogeneity of the articles was calculated using the I 2 index. This research was exempted after review by the institutional review board at the institution of the principal investigator.

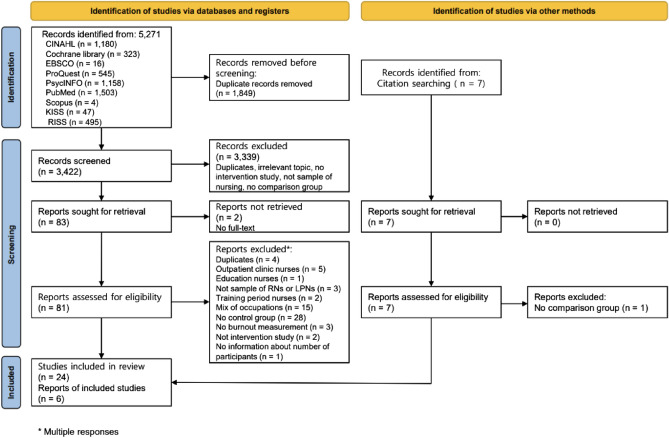

Study selection

We retrieved 5271 articles from the initial search. After reviewing the title and abstract, 5188 were excluded (duplicates, no intervention study, no comparison group, not target population). During the full-text review, 59 articles were excluded (no full-text, duplicates, no intervention study, no comparison group, not target population). Through reference check, six articles were included. Finally, 30 articles were included in our final analysis (Fig. 1 ).

Study selection.

Study characteristics

The characteristics of studies and interventions are described in Table 2 . Of the 30 articles, 12 were randomized controlled trials 26 , 28 , 33 – 42 and 18 were quasi-experimental studies 27 , 30 , 31 , 43 – 57 . Nineteen studies were conducted in Asia (Korea = 14, China = 3, India = 1, and Japan = 1). The types of publication were journals (n = 26) and thesis (n = 4). Participants were mostly women, with the female gender ranging from 71.9 to 100%. The age range of the participants was 24–46 years. There were between 21 and 296 participants, for a total of 1935, with 975 in the experimental group and 960 in the control group.

Characteristics of the included studies.

C comparison group, E experimental group, MBI Maslach Burnout Inventory scale, OLBI Oldenburg Burnout Inventory, ProQoL Professional Quality of Life Scale, RCT Randomized controlled trial, N/A not available.

The most common interventions provided for burnout reduction were mindfulness-based stress reduction programs (n = 5) and face-to-face group format (n = 24). The duration of the intervention varied from one day to eight months. In most studies, control groups involved the waitlist group (n = 12) rather than an active control group. MBI (n = 19), ProQoL (n = 8) and others (n = 3) were the instruments used to measure burnout. Burnout was most often measured twice, before the intervention and immediately post-intervention. In three studies 37 , 38 , 44 , burnout was measured at baseline and follow-up only, not immediately post-intervention.

Risk-of-bias

Risk-of-bias is described in Table 2 . In general, the level of risk of bias for 12 randomized controlled trials was “some concern.” The level of risk of bias for the 18 quasi-experimental studies was “low risk of bias” for 15 studies, “moderate risk of bias” for two studies, and non-assessable due to limited information for one study.

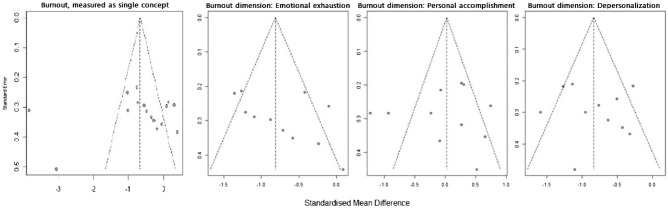

The risk of publication bias was evaluated using a funnel plot (Fig. 2 ). The plot is symmetrical when publication bias is at minimum 58 . Studies with a small sample size were on the lower side, while those with a large sample size were on the opposite side. The small number of articles used in our study was a risk factor because it could affect the precision of the results. Among 30 articles, three articles 37 , 38 , 44 that did not conduct a post-test were excluded for meta-analysis. Sixteen articles measured burnout as a single concept 26 – 28 , 31 , 34 , 35 , 40 , 45 – 47 , 49 – 52 , 54 , 56 and 11 measured burnout as three dimensions: emotional exhaustion, depersonalization, and low personal accomplishment 30 , 33 , 36 , 39 , 41 – 43 , 48 , 53 , 55 , 57 . There was one outlier among articles that measured burnout as a single concept.

Funnel plots.

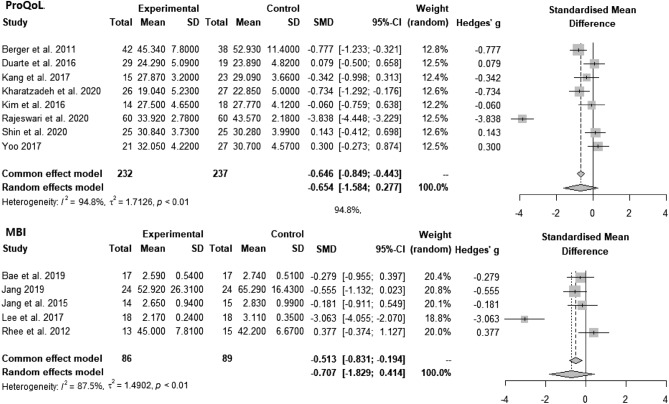

Meta-analysis

Instruments that measured burnout as a single concept were ProQoL (n = 8), MBI (n = 5), burnout questionnaire (n = 2), and OLBI (n = 1). Meta-analysis of articles that used ProQoL and MBI are described in Fig. 3 . For the articles that used ProQoL, the pooled analysis showed that intervention could statistically alleviate burnout (SMD = − 0.654, CI = − 1.584, 0.277, p < 0.01, I 2 = 94.8%). For the articles that used the MBI, the pooled analysis showed that intervention could statistically alleviate burnout (SMD = − 0.707, CI = − 1.829, 0.414, p < 0.01, I 2 = 87.5%).

Forest plots: Effect of interventions on burnout measured by ProQoL and MBI.

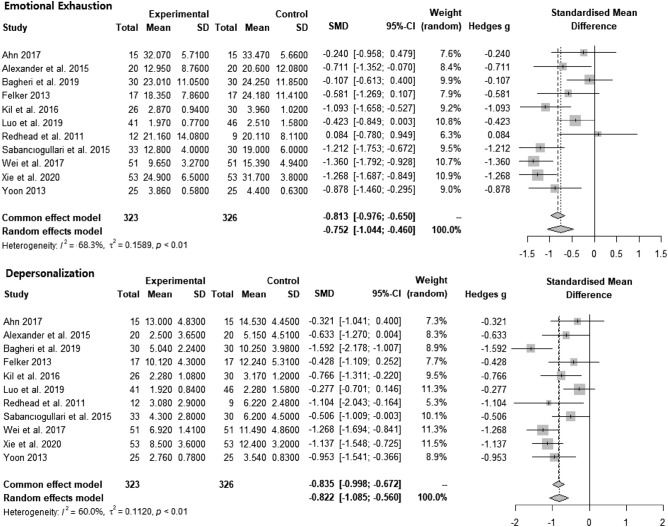

The meta-analysis of burnout interventions as three dimensions (n = 11) is described in Fig. 4 . The pooled analysis showed that interventions could statistically significantly reduce emotional exhaustion (SMD = − 0.752, CI = − 1.044, − 0.460, p < 0.01, I 2 = 68.3%) and depersonalization (SMD = − 0.822, CI = − 1.085, − 0.560, p < 0.01, I 2 = 60.0%). For improving low personal accomplishment, the pooled analysis result was not statistically significant.

Forest plots: effect of intervention on emotional exhaustion and depersonalization.

In this systematic review and meta-analysis, we analyzed 30 and 24 articles, respectively. Among 30 articles, more than half (n = 19) were published in Asia. Although nurse burnout is a global phenomenon, the prevalence of nurse burnout studies conducted in Asia might indicate the significance of the issue of nurse burnout in Asian countries. This notion is supported by a recent meta-analysis study on the global prevalence of nurse burnout, which reported that Southeast Asia and the Pacific region had a significantly higher prevalence of nurse burnout among si× global regions 6 . In Asia, nurses encounter poor working conditions such as low nurse patient ratios 59 and a rapidly aging population. High prevalence of nurse burnout in Asian countries might have drawn the nurse administrators and nursing scholars to research on nurse burnout interventions.

Our systematic review revealed that a mindfulness-based program was the most frequently used intervention for nurse burnout. Meta-analysis studies 19 have shown that mindfulness-based programs are effective in reducing nurse burnout. However, burnout refers to a state of physical, mental, and social exhaustion that may require various interventions. A systematic review of health professional burnout programs revealed that a vast array of interventions have been adopted alone or in combination 24 . Although mindfulness-based programs are helpful in lowering burnout level, their role might be limited to managing burnout rather than preventing or managing situations for burnout 60 . In many cases, the causes of burnout are multifaceted, which include but are not limited to issues with limited manpower, working longer shifts, not having schedule flexibility, and responding to high work and psychological demands 11 . Systematic support to improve work environments and tailored programs to train nurses to prevent repeated situations are needed.

All articles were appraised for risk of bias. The most concerning realm for risk of bias in both the randomized controlled trials and quasi-experimental studies was bias in the measurement of outcomes that were appraised as “some concern” or “moderate risk of bias.” As burnout is a subjective concept, all the interventions used a self-reported survey to measure the outcome, leading to a moderate risk of bias. To overcome this, biological indicators for burnout could be utilized. However, we would like to note that people are experts in their own feelings and psychological health. In measuring psychological concepts such as burnout, the concept of risk of bias should be re-assessed.

In our meta-analysis of articles that measured burnout as a single concept with ProQoL and MBI, the results favored intervention. Similarly, results of previous meta-analyses of various burnout interventions provided to health professionals reported that burnout could be reduced 23 . In this study, the authors argued that various factors, such as coping strategies, emotional regulation skills, and resilience, were enhanced through diverse burnout interventions and bridged health professionals’ burnout to wellness. Likewise, various programs could be utilized solitarily or in combination to reduce nurse burnout.

When burnout was measured as three dimensions, emotional exhaustion and depersonalization were lowered, leaving no evidence for increasing low personal accomplishment. In contrast, a recent meta-analysis study on burnout intervention for primary healthcare professionals reported that interventions had beneficial effects on all three dimensions of burnout, including low personal accomplishment 61 . In the previous meta-analysis study, 78.5% of the participants were physicians, while only 20.1% were nurses. This was one of the most significant differences between the studies. The nature of the profession in achieving personal accomplishment may explain the differences in intervention effect on low personal accomplishment. Personal accomplishment for nurses may be more closely tied to a workplace system. For instance, a study that measured personal accomplishment found that it was positively correlated with aspects of the workplace such as control, community, fairness, and values 62 . In accordance with this argument, a meta-analysis that examined the long-term effect of burnout intervention on nurses found that improvement in low personal accomplishment lasted only six months, whereas improvement in emotional exhaustion and depersonalization lasted a year 20 . The authors of this study also explained that low personal accomplishment is difficult to change in the long term because it is reliant on the work environment. Another possible reason for the burnout intervention not favoring low personal accomplishment might be owing to the contents of the intervention focusing on problem-solving skills, such as stress reduction, coping with the problem, and empowering the participants, which are helpful for emotional exhaustion and depersonalization.

Implications for future research are suggested as follows. This study revealed that the majority of burnout interventions for clinical nurses were delivered as face-to-face group programs, which could be challenging to implement during a pandemic such as COVID-19. Combining online and offline burnout programs may be an option for reducing the risk of infection. Despite the fact that clinical nurses benefit from burnout programs, they may require consistent support and feedback to continue the program 63 . Continual active feedback may be necessary for the implementation and maintenance of the burnout program for clinical nurses. A number of scholars view burnout as three dimensions in line with the ICD-11 definition of burnout and meta-analysis studies on the prevalence and risk factors for burnout explained burnout as three dimensions 6 , 64 , meaning there is ample evidence on the dimensions of burnout. However, when examining the effect of burnout interventions, burnout is often measured as a single concept. Burnout interventions should be designed to target all three areas. Additionally, more time and effort might be needed to promote personal accomplishment.

Limitations

In this study, we focused on nurses providing direct care in hospitals, excluding those who worked in outpatient clinics. Thus, our findings are limited to clinical nurses. The articles’ language was limited to English and Korean, half of which were in Korean. In addition, we limited our search to the past 10 years to reflect the reality of the burnout intervention effect, which may have caused selection bias. When the risk of bias was appraised, we identified some concerns, including moderate concerns. In addition, articles analyzed in this study used different instruments to measure burnout. We acknowledge the heterogeneity of the data, which is assumed by meta-analysis study. Thus, readers of this article should be aware of the risk of bias in the results and heterogeneity of the articles in instruments. The protocol of this systematic review and meta-analysis was not registered.

Conclusions

Thirty articles were included in the systematic review and 24 in the meta-analysis. Most of the evidence for nurse burnout was based on face-to-face group programs, which could be transformed into a virtual space in the post-COVID-19 era. Pooled analysis suggested that interventions could reduce burnout when measured as a single concept and reduce the emotional exhaustion and depersonalization dimensions of burnout. However, we could not find evidence for burnout interventions effectively promoting personal accomplishment.

Abbreviations

Confidence interval

International Classification of Disease-11

Maslach Burnout Inventory

Not available

Oldenburg Burnout Inventory

Professional Quality of Life Scale

Randomized controlled trial

Standardized mean difference

Author contributions

C.C. envisioned the systematic review and drafted the manuscript. C.C. and M.L. are involved in data search and assessing articles for eligibility and the risk of bias. C.C. and M.L. read and approved the final version of the manuscript. C.C. and M.L. wrote the manuscript together (M.L. was mainly in charge of the background and discussion and C.C. was mainly involved in the method and discussion). All authors reviewed and revised the manuscript.

This work was supported by the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) grant funded by the Korea government (MSIT) (No. 2021R1A2C2008166).

Data availability

The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are not publicly available due to the IRB restriction but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

- 1. Freudenberger HJ. Staff burn-out. J. Soc. Issues. 1974;30(1):159–165. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-4560.1974.tb00706.x. [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 2. Stamm, B. H. The Concise ProQOL Manual . In Pocatello: ProQOL.org (2010).

- 3. Maslach C. Burned-out. Hum. Behav. 1976;5(9):16–22. [ Google Scholar ]

- 4. Kim SH, Yang YS. A Meta analysis of variables related to Burnout of nurse in Korea. J. Dig. Converg. 2015;13(8):387–400. doi: 10.14400/JDC.2015.13.8.387. [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 5. Nabizadeh-Gharghozar Z, Adib-Hajbaghery M, Bolandianbafghi S. Nurses' job burnout: A hybrid concept analysis. J. Caring Sci. 2020;9(3):154–161. doi: 10.34172/jcs.2020.023. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 6. Woo T, Ho R, Tang A, Tam W. Global prevalence of burnout symptoms among nurses: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Psychiatr. Res. 2020;123:9–20. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2019.12.015. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 7. Pradas-Hernández L, et al. Prevalence of burnout in paediatric nurses: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS ONE. 2018;13(4):e0195039. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0195039. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 8. Ramirez-Baena L, et al. A multicentre study of burnout prevalence and related psychological variables in medical area hospital nurses. J. Clin. Med. 2019;8(1):92. doi: 10.3390/jcm8010092. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 9. Bruyneel A, Smith P, Tack J, Pirson M. Prevalence of burnout risk and factors associated with burnout risk among ICU nurses during the COVID-19 outbreak in French speaking Belgium. Intensive Crit. Care Nurs. 2021;65:103059. doi: 10.1016/j.iccn.2021.103059. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 10. Morgantini LA, et al. Factors contributing to healthcare professional burnout during the COVID-19 pandemic: A rapid turnaround global survey. PLoS ONE. 2020;15(9):e0238217. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0238217. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 11. Dall'Ora C, Ball J, Reinius M, Griffiths P. Burnout in nursing: A theoretical review. Hum. Resour. Health. 2020;18(1):41. doi: 10.1186/s12960-020-00469-9. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 12. Salyers MP, et al. The relationship between professional burnout and quality and safety in healthcare: A meta-analysis. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2017;32(4):475–482. doi: 10.1007/s11606-016-3886-9. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 13. Montgomery AP, et al. Nurse burnout predicts self-reported medication administration errors in acute care hospitals. J. Healthc. Qual. 2021;43(1):13–23. doi: 10.1097/JHQ.0000000000000274. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 14. Nantsupawat A, Nantsupawat R, Kunaviktikul W, Turale S, Poghosyan L. Nurse burnout, nurse-reported quality of care, and patient outcomes in Thai hospitals. J. Nurs. Scholarsh. 2016;48(1):83–90. doi: 10.1111/jnu.12187. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 15. Rudman A, Arborelius L, Dahlgren A, Finnes A, Gustavsson P. Consequences of early career nurse burnout: A prospective long-term follow-up on cognitive functions, depressive symptoms, and insomnia. EClinical Med. 2020;27:100565. doi: 10.1016/j.eclinm.2020.100565. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 16. Ashrafi Z, Ebrahimi H, Khosravi A, Navidian A, Ghajar A. The relationship between quality of work life and burnout: A linear regression structural-equation modeling. Health Scope. 2018;7(1):e68266. doi: 10.5812/jhealthscope.68266. [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 17. Molina-Praena J, et al. Levels of burnout and risk factors in medical area nurses: A meta-analytic study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 2018;15(12):2800. doi: 10.3390/ijerph15122800. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 18. Deldar K, Froutan R, Dalvand S, Gheshlagh RG, Mazloum SR. The relationship between resiliency and burnout in Iranian nurses: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Open Access Maced J. Med. Sci. 2018;6(11):2250–2256. doi: 10.3889/oamjms.2018.428. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 19. Suleiman-Martos N, et al. The effect of mindfulness training on burnout syndrome in nursing: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Adv. Nurs. 2020;76(5):1124–1140. doi: 10.1111/jan.14318. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 20. Lee HF, Kuo CC, Chien TW, Wang YR. A meta-analysis of the effects of coping strategies on reducing nurse burnout. Appl. Nurs. Res. 2016;31:100–110. doi: 10.1016/j.apnr.2016.01.001. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 21. de-Oliveira SM, de-Alcantara-Sousa LV, Vieira-Gadelha MDS, do-Nascimento VB. Prevention actions of burnout syndrome in nurses: An integrating literature review. Clin. Pract. Epidemiol. Ment. Health. 2019;15:64–73. doi: 10.2174/1745017901915010064. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 22. Aryankhesal A, et al. Interventions on reducing burnout in physicians and nurses: A systematic review. Med. J. Islam Repub. Iran. 2019;33:77. doi: 10.34171/mjiri.33.77. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 23. Zhang XJ, Song Y, Jiang T, Ding N, Shi TY. Interventions to reduce burnout of physicians and nurses: An overview of systematic reviews and meta-analyses. Medicine. 2020;99(26):e20992. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000020992. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 24. O’Leary KJ, Sehgal NL, Terrell G, Williams MV, High Performance Teams and the Hospital of the Future Project Tea Interdisciplinary teamwork in hospitals: A review and practical recommendations for improvement. J. Hosp. Med. 2012;7(1):48–54. doi: 10.1002/jhm.970. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 25. Dubale BW, et al. Systematic review of burnout among healthcare providers in sub-Saharan Africa. BMC Public Health. 2019;19(1):1–20. doi: 10.1186/s12889-019-7566-7. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 26. Dincer B, Inangil D. The effect of emotional freedom techniques on nurses' stress, anxiety, and burnout levels during the COVID-19 pandemic: A randomized controlled trial. Explore. 2021;17(2):109–114. doi: 10.1016/j.explore.2020.11.012. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 27. Kim HR, Yoon SH. Effects of group rational emotive behavior therapy on the nurses’ job stress, burnout, job satisfaction, organizational commitment and turnover intention. J. Korean Acad. Nurs. 2018;48(4):432–442. doi: 10.4040/jkan.2018.48.4.432. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 28. Rajeswari H, Sreelekha BK, Nappinai S, Subrahmanyam U, Rajeswari V. Impact of accelerated recovery program on compassion fatigue among nurses in South India. Iran. J. Nurs. Midwifery Res. 2020;25(3):249. doi: 10.4103/ijnmr.IJNMR_218_19. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 29. Maslach C, Jackson SE, Leiter MP. Maslach Burnout Inventory, Manual. 3. Consulting Psychologists Press; 1996. [ Google Scholar ]

- 30. Bagheri T, Fatemi MJ, Payandan H, Skandari A, Momeni M. The effects of stress-coping strategies and group cognitive-behavioral therapy on nurse burnout. Ann. Burns Fire Disasters. 2019;32(3):184. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 31. Jang OJ, Ryu UJ, Song HJ. The effects of a group art therapy on job stress and burnout among clinical nurses in oncology units. J. Korean Clin. Nurs. Res. 2015;21(3):366–376. [ Google Scholar ]

- 32. Page MJ, et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. Int. J. Surg. 2021;88:105906. doi: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2021.105906. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 33. Alexander GK, Rollins K, Walker D, Wong L, Pennings J. Yoga for self-care and burnout prevention among nurses. Workplace Health Saf. 2015;63(10):462–470. doi: 10.1177/2165079915596102. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 34. Berger R, Gelkopf M. An intervention for reducing secondary traumatization and improving professional self-efficacy in well baby clinic nurses following war and terror: A random control group trial. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2011;48(5):601–610. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2010.09.007. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 35. Kharatzadeh H, Alavi M, Mohammadi A, Visentin D, Cleary M. Emotional regulation training for intensive and critical care nurses. Nurs. Health Sci. 2020;22(2):445–453. doi: 10.1111/nhs.12679. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 36. Kil KH, Song YS. Effects on psychological health of nurses in tertiary hospitals by applying a self-cosmetology training program. J. Korean Soc. Cosm. 2016;22(6):1444–1453. [ Google Scholar ]

- 37. Kubota Y, et al. Effectiveness of a psycho-oncology training program for oncology nurses: A randomized controlled trial. Psychooncology. 2016;25(6):712–718. doi: 10.1002/pon.4000. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 38. Özbaş AA, Tel H. The effect of a psychological empowerment program based on psychodrama on empowerment perception and burnout levels in oncology nurses: Psychological empowerment in oncology nurses. Palliat Support Care. 2016;14(4):393–401. doi: 10.1017/S1478951515001121. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 39. Redhead K, Bradshaw T, Braynion P, Doyle M. An evaluation of the outcomes of psychosocial intervention training for qualified and unqualified nursing staff working in a low-secure mental health unit. J. Psychiatr. Ment. Health Nurs. 2011;18(1):59–66. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2850.2010.01629.x. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 40. Shin YK, Lee SY, Lee JM, Kang P, Seol GH. Effects of short-term inhalation of patchouli oil on professional quality of life and stress levels in emergency nurses: A randomized controlled trial. J. Altern. Complement Med. 2020;26(11):1032–1038. doi: 10.1089/acm.2020.0206. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 41. Wei, R., Ji, H., Li, J. & Zhang, L. Active intervention can decrease burnout in ED nurses. J. Emerg. Nurs. 43 (2), 145–149 (2017). [ DOI ] [ PubMed ]

- 42. Xie C, et al. Educational intervention versus mindfulness-based intervention for ICU nurses with occupational burnout: A parallel, controlled trial. Complement Ther. Med. 2020;52:102485. doi: 10.1016/j.ctim.2020.102485. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 43. Ahn, M. N. The effect of mindfulness-based stress reduction program on nurse's stress, burnout, sleep and happiness. Master’s thesis, Eulji University (Daejeon, 2017).

- 44. Alenezi A, McAndrew S, Fallon P. Burning out physical and emotional fatigue: Evaluating the effects of a programme aimed at reducing burnout among mental health nurses. Int. J. Ment. Health Nurs. 2019;28(5):1045–1055. doi: 10.1111/inm.12608. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 45. Bae HJ, Eun Y. Effects of mindfulness-based stress reduction program for small and medium sized hospital nurses. Korean J. Stress Res. 2019;27(4):455–463. doi: 10.17547/kjsr.2019.27.4.455. [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 46. Choi KH, Kwon S, Hong M. The effect of an empowerment program for advanced beginner hospital nurses. J. Korean Data Anal. Soc. 2016;18(2):1079–1092. [ Google Scholar ]

- 47. Duarte J, Pinto-Gouveia J. Effectiveness of a mindfulness-based intervention on oncology nurses’ burnout and compassion fatigue symptoms: A non-randomized study. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2016;64:98–107. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2016.10.002. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 48. Felker, A. J. An Examination of yoga as a stress reduction intervention for nurses. Doctoral dissertation, Walden University (Minnesota, 2013).

- 49. Jang, Y. M. Development and evaluation of nurse's workplace mutual respect program, Doctoral dissertation, Eulji University (Daejeon, 2019).

- 50. Kang HJ, Bang KS. Development and evaluation of a self-reflection program for intensive care unit nurses who have experienced the death of pediatric patients. J. Korean Acad. Nurs. 2017;47(3):392–405. doi: 10.4040/jkan.2017.47.3.392. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 51. Kim YA, Park JS. Development and application of an overcoming compassion fatigue program for emergency nurses. J. Korean Acad. Nurs. 2016;46(2):260–270. doi: 10.4040/jkan.2016.46.2.260. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 52. Lee SM, Sung KM. The effects of violence coping program based on middle-range theory of resilience on emergency room nurses' resilience, violence coping, nursing competency and burnout. J. Korean Acad. Nurs. 2017;47(3):332–344. doi: 10.4040/jkan.2017.47.3.332. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 53. Luo YH, et al. An evaluation of a positive psychological intervention to reduce burnout among nurses. Arch. Psychiatr. Nurs. 2019;33(6):186–191. doi: 10.1016/j.apnu.2019.08.004. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 54. Rhee JS, Kim SH, Lee WK, Shin JG. The effects of MBSR(Mindfulness based stress reduction) program on burnout of psychiatric nurses: Pilot study. J. Korean Assoc. Soc. Psychiatry. 2012;17(1):25–31. [ Google Scholar ]

- 55. Sabancıogullari S, Dogan S. Effects of the professional identity development programme on the professional identity, job satisfaction and burnout levels of nurses: A pilot study. Int. J. Nurs. Pract. 2015;21(6):847–857. doi: 10.1111/ijn.12330. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 56. Yoo, D. Effect of an expressive writing program on professional quality of life and resilience of intensive care unit nurses. In Master’s thesis, Cha University (Gyeonggi, 2017).

- 57. Yoon HS. Effects of the happy arts therapy program to psychological well-being and emotional exhaust in nurse practitioners. Off. J. Korean Soc. Dance Sci. 2013;29(29):53–74. [ Google Scholar ]

- 58. Field AP, Gillett R. How to do a meta-analysis. Br. J. Math. Stat. Psychol. 2010;63(3):665–694. doi: 10.1348/000711010X502733. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 59. Drennan VM, Ross F. Global nurse shortages: The facts, the impact and action for change. Br. Med. Bull. 2019;130(1):25–37. doi: 10.1093/bmb/ldz014. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 60. Green AA, Kinchen EV. The effects of mindfulness meditation on stress and burnout in nurses. J. Holist. Nurs. 2021;39(4):356–368. doi: 10.1177/08980101211015818. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 61. Salvado M, Marques DL, Pires IM, Silva NM. Mindfulness-based interventions to reduce burnout in primary healthcare professionals: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Healthcare (Basel, Switzerl.) 2021;9(10):1342. doi: 10.3390/healthcare9101342. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 62. Whittington KD, Shaw T, McKinnies RC, Collins SK. Promoting personal accomplishment to decrease nurse burnout. Nurse Lead. 2021;19(4):416–420. doi: 10.1016/j.mnl.2020.10.008. [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 63. Wu X, Hayter M, Lee AJ, Zhang Y. Nurses' experiences of the effects of mindfulness training: A narrative review and qualitative meta-synthesis. Nurse Educ. Today. 2021;100:104830. doi: 10.1016/j.nedt.2021.104830. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 64. Galanis P, Vraka I, Fragkou D, Bilali A, Kaitelidou D. Nurses' burnout and associated risk factors during the COVID-19 pandemic: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Adv. Nurs. 2021;77(8):3286–3302. doi: 10.1111/jan.14839. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

- View on publisher site

- PDF (2.3 MB)

- Collections

Similar articles

Cited by other articles, links to ncbi databases.

- Download .nbib .nbib

- Format: AMA APA MLA NLM

Add to Collections

Clinical intervention research in nursing

Affiliation.

- 1 King's College London, The Florence Nightingale School of Nursing & Midwifery, Primary and Intermediate Care Department, James Clerk Maxwell Building, Waterloo Road, London SE1 8WA, United Kingdom. [email protected]

- PMID: 18930228

- DOI: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2008.08.012

As a healthcare profession nursing has a duty to develop practices that contribute to the health and well being of patients. The aim of this paper is to discuss current issues in clinical research within nursing. The paper defines clinical interventions research as a theoretically based, integrated and sequential approach to clinical knowledge generation. The paper provides specific criteria for defining a clinical intervention together with an overview of the stages involved in clinical research from problem identification to implementing knowledge in practice. The paper also explored the extent to which nursing research was focussed on clinical issues, through a snapshot review of all the original research papers in Europe's three leading nursing research journals. In total of 517 different papers were included and classified in the review. Of these 88% (n=455) were classified as non-clinical intervention and 12% (n=62) as clinical intervention studies. The paper examined the intervention studies in detail examining: the underpinning theory; linkage to previous (pre-clinical) work; evidence of granularity; protocol clarity (generalisable and parsimonious); the phase of knowledge development; and evidence of safety (adverse event reporting). The paper discusses some of the shortcomings of interventions research in nursing and suggests a number of ideas to help address these problems, including: a consensus statement on interventions research in nursing; a register of nursing intervention studies; the need for nursing to develop clinical research areas in which to develop potential interventions (nursing laboratories); and a call for nursing researchers to publish more research in nursing specific journals.

Publication types

- Nursing Research*

- Research article

- Open access

- Published: 02 May 2017

Describing the implementation of an innovative intervention and evaluating its effectiveness in increasing research capacity of advanced clinical nurses: using the consolidated framework for implementation research

- Gabrielle McKee ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-0211-5330 1 ,

- Margaret Codd 2 ,

- Orla Dempsey 3 ,

- Paul Gallagher 2 &

- Catherine Comiskey 1

BMC Nursing volume 16 , Article number: 21 ( 2017 ) Cite this article

12k Accesses

32 Citations

6 Altmetric

Metrics details

Despite advanced nursing roles having a research competency, participation in research is low. There are many barriers to participation in research and few interventions have been developed to address these. This paper aims to describe the implementation of an intervention to increase research participation in advanced clinical nursing roles and evaluate its effectiveness.

The implementation of the intervention was carried out within one hospital site. The evaluation utilised a mixed methods design and a implementation science framework. All staff in advanced nursing roles were invited to take part, all those who were interested and had a project in mind could volunteer to participate in the intervention. The intervention consisted of the development of small research groups working on projects developed by the nurse participant/s and supported by an academic and a research fellow. The main evaluation was through focus groups. Output was analysed using thematic analysis. In addition, a survey questionnaire was circulated to all participants to ascertain their self-reported research skills before and after the intervention. The results of the survey were analysed using descriptive statistics. Finally an inventory of research outputs was collated.

In the first year, twelve new clinical nurse-led research projects were conducted and reported in six peer reviewed papers, two non-peer reviewed papers and 20 conference presentations. The main strengths of the intervention were its promptness to complete research, to publish and to showcase clinical innovations. Main barriers identified were time, appropriate support from academics and from peers. The majority of participants had increased experience at scientific writing and data analysis.

This study shows that an intervention, with minor financial resources; a top down approach; support of a hands on research fellow; peer collaboration with academics; strong clinical ownership by the clinical nurse researcher; experiential learning opportunities; focused and with needs based educational sessions, is an intervention that can both increase research outputs and capacity of clinically based nurses. Interventions to further enhance nursing research and their evaluation are crucial if we are to address the deficit of nurse-led patient-centred research in the literature.

Peer Review reports

Across the world there has been significant expansion of the nursing role and the competencies within it. These have already demonstrated added value to patients and services [ 1 , 2 ]. Within the more advanced nursing roles one of the competencies includes research. With the expectancy of advanced nursing staff to be research active and undertake research there is clearly a need not only to provide research capacity development and ongoing support but also to evaluate it’s effectiveness. The impact of these roles on patient care is already evident. This may in part be due to the increased research role, enabling quality improvements to be even more systematic and more evidence based [ 3 ]. There is a strong need in the literature for more research that is patient centred [ 4 ]. These new roles and their impact on practice can provide this. But it can only do this if there is sufficient research capacity within the nurses in these roles.

Research capacity building is a broad concept that encompasses some or many aspects of research ranging from awareness, knowledge, skills, understanding, utilisation, data collection, presentations through to participation [ 5 – 7 ]. While there is an identified inconsistency in the meaning of the term research capacity building, within this paper it refers to involvement at all levels of the research process from question design to dissemination [ 5 , 8 ]. Research capacity building has been identified as a priority in nursing research and development [ 5 , 9 ]. However, within nursing to date the emphasis in research capacity building has been mainly in nurse academics [ 5 , 9 , 10 ], rather than in nurses with a clinical role [ 7 , 9 , 11 , 12 ].

Clinical nurse participation in research is relatively low [ 7 , 11 ]. Many barriers to participation have been identified. Personal barriers include nurses’ attitudes [ 13 , 14 ], poor knowledge about research [ 7 , 12 – 16 ], lack of opportunity or experience [ 14 , 15 , 17 ], need for research skills [ 9 , 14 , 17 , 18 ], lack of qualifications [ 12 ], lack of interest [ 7 ], lack of confidence [ 14 , 15 ] and lack of motivation [ 13 – 15 , 19 ]. At organisational level, other barriers to research have been identified and include, lack of research supervision [ 7 ], lack of support [ 7 , 11 , 13 – 17 , 20 ], lack of reward [ 11 ], power hierarchies [ 12 , 14 ], lack of mentorship [ 12 ], lack of time [ 7 , 11 – 13 , 15 , 17 , 18 , 20 , 21 ], and poor resources and funding [ 11 – 16 , 18 , 22 ].

Review of the literature indicates that initiatives to enhance clinical research capacity should address three main areas; leadership, expertise and capacity [ 11 , 23 ]. Strong leadership has long been advocated as a key element in clinical research capacity building [ 8 , 10 , 21 , 22 , 24 ]. Other features that reflect a strong leadership presence include, the development of a strategy, formalising research policies and support [ 8 , 20 , 24 , 25 ], identifying priorities [ 24 ], the development of a research culture [ 15 , 20 , 22 ], an organisational need for research [ 8 ] and the use of a steering committee [ 11 , 20 ].

The features needed to provide expertise and capacity have some common characteristics. The use of collaborations or networks [ 8 , 22 , 23 , 26 , 27 ], is a common feature of support advocated [ 25 ]. This can be of several different forms but usually embraces using experts in the area [ 8 ], either academics [ 11 , 28 ] or other clinicians both within and outside of the discipline [ 13 ] and utilising different modes of mentorship [ 29 ].

Sourcing funding is also strongly advocated as a method of providing support. Whether this is to provide direct support to single researchers, finding funding for research facilitator posts or other resources [ 8 , 25 ], investments in infrastructure or other aspects of an initiative [ 20 , 25 ] or building elements of sustainability and continuity [ 11 ]. Support can also be provided through the development of an educational programme or educational providing opportunities [ 8 , 9 , 13 , 19 , 23 , 25 , 30 ] or through the use of journal clubs [ 13 ] newsletters and monthly research meetings [ 19 ]. But overall it is evident that the leadership model utilised should provide a good support management system that will, in addition to the above, increase awareness of research within units [ 8 , 25 ] so as to increase the capacity of individuals to engage in research.

Additional features that have been advocated in interventions used to enhance clinical research capacity building include ensuring the research is ‘close’ to practice, that the clinical staff identify the research ideas [ 11 ] or jointly identify the ideas [ 28 ], that small research teams are used [ 19 , 20 , 31 ], that these are clinician led [ 20 , 31 ] and that the outcome of the research not only informs local practice but is disseminated [ 8 , 11 , 25 , 28 , 30 ].

Paget et al. [ 18 ] concluded that while interventions to increase capacity in nurses are well received the evidence of their effectiveness is limited. This is well evidenced from the paucity of studies evaluating the effectiveness of research capacity building initiatives [ 4 , 11 , 12 , 27 , 31 , 32 ]. A further barrier to the measurement and dissemination of the effectiveness of interventions is the lack of use of consistent tools [ 33 ]. Despite these limitations, it has been shown that when some of the key aforementioned features are present there is an increase in knowledge post-intervention [ 13 , 20 , 32 ]. Post-intervention there was also a change in attitude towards research and a culture of research was developed resulting in an increase in research related activities [ 13 , 25 , 27 , 31 ]. The evaluations identified many of the strengths of the implementations such as support, leadership, collaboration, visibility but also identified still outstanding weaknesses such as time and resources [ 26 , 27 , 31 ].

So although there has been a vast amount of literature on the barriers to research participation by clinical nursing staff, and a lot of literature about the elements that would promote good research capacity, much more is needed with regard to the evaluation of interventions implemented to improve research capacity.

It was evident from the literature that a successful standard intervention did not exist, but that local, national, policy and other influences have to be taken into account. Future interventions must not only evaluate their outcomes and effectiveness but contextualise them thoroughly. To address this, suitable frameworks need to be utilised in development, implementation and reporting of such interventions. The relatively recent developed consolidated framework for implementation science, as originally described by Damschroder et al. [ 34 ] and further detailed in Breimaier et al., [ 33 – 35 ] would be appropriate. This framework has already been utilised widely in research in general and in health sciences research [ 36 ]. It is a consolidation of many theories and therefore provides a comprehensive framework, uses standardised structures and common language that allow readers to identify the most important elements of all phases of an implementation. In particular, it allows for the contextualisation of the intervention to be systematically addressed, which as seen from the literature is essential for future research in this area.

The aim of this paper is to describe the implementation of an intervention and evaluate its effectiveness in increasing research capacity in advanced clinical nursing roles.

Research design and conceptual framework

The evaluation utilised a mixed methods design and the consolidated framework for implementation science as a conceptual framework.

Intervention

From inception to analysis the intervention developed to increase research capacity in advanced clinical nursing in an acute urban hospital setting, utilised the consolidated framework for implementation science. This methods section describes the intervention using the five domains of this framework. These are, intervention characteristics, the social context, the local context, the characteristics of the individuals involved and the process including evaluation [ 34 , 35 ].

Intervention characteristics

The intervention developed included, skill development, support with quantitative methodology and support from researchers experienced in both carrying out research and research dissemination. The key characteristics of the intervention were leadership, steering group, funding, small research groups with post-doctoral research fellow support, clinical and academic nurse researchers, focused clinical nurse-led research questions, peer mentorship, experiential learning and, the provision of additional educational sessions based on needs (Fig. 1 ). Funding was sourced to employ a part time post-doctoral researcher with quantitative and health research experience to act as a research facilitator and provide both expertise and sharing of research workload with the nurse researchers.

Outline of intervention components

Through the utilisation of the skills of both clinical and academic partners the intervention aimed to facilitate the understanding, development and application of research skills, to produce demonstrable outputs for patient care and research, e.g. statistical analysis, study design, academic writing and submission of papers for publication, and practice development.

Outer setting (Social setting)

The implementation of the intervention facilitated development, implementation, evaluation and dissemination of clinical innovations within the hospital, all of which were believed to have a direct effect on patient outcomes. To increase the quality of the implementation, in addition to the international literature evidence, the academic partner consulted with international clinical and academic institutes who had interventions in place for increasing research in clinical nursing staff.

Local context (Inner setting)

The hospital site was a large (1020 bed) urban acute teaching hospital with several national disease centres and the academic partner was a university School of Nursing and Midwifery, both in Ireland. Nursing within the hospital had a well-developed centre for practice development that mentored and supported innovation and development in practice. However, there was no existing formal research infrastructure to support the research needs of the new advanced clinical nurses on a formal basis.

Characteristics of participants

The development was driven by leaders high in the hierarchy of the hospital (Director of Nursing and Assistant Directors of Nursing) in collaboration with research personnel in the linked academic institute (Director of Research and the Director of the Centre for Practice and Healthcare Innovation). The steering group included the above (only one Assistant Director of Nursing), the Nurse Practice Development Co-ordinator and the Head of the Centre for Learning and Development.

The inclusion criteria, for participation in the intervention, were nursing staff at clinical nurse specialist or advanced nurse practitioner level (advanced nursing roles) with a clinically based research topic of interest they wished to develop or wanted support with. Research nurses were not eligible to apply. Peer mentoring was to be provided by the academics within small research groups.

The intervention’s development and implementation took place from 2010 to 2013. The planning, engaging the participants and executing of the intervention are described herein.

Based on the literature an intervention with the aforementioned elements was developed by the steering group (Fig. 1 ). Table 1 indicates the main steps in the development of the innovation, the purpose, rationale, actions and the main stakeholders involved.

The Director of Nursing mailed all the advanced clinical nurses in the hospital and invited those with a research topic they wished to develop or have support with, to submit an outline of their project to the steering committee. Academics with relevant experience in the research topic or methodology of the advanced nurse projects were invited to become members of the small research groups. Groups therefore included the advanced clinical nurse/s who had developed the research question, the postdoctoral research fellow and usually one academic.

The small research groups then developed their own schedule of meetings, work and appropriate target outputs. The different aspects of the research process ranging from searching the literature to research dissemination were carried out by any appropriate member of the group, achieving a balance between utilising research strengths and developing areas of weakness. The data analysis was mainly the role of the post-doctoral research facilitator and the data cleaning was carried out by both the post-doctoral research facilitator and the advanced clinical nurse researcher. It was planned that within the research groups there would be experiential development of research skills using peer mentorship in a supportive, collaborative team environment.

To further enhance the research skills of the clinical nurses additional direct support mechanisms were introduced. The clinical nurse researchers were invited to attend the research support seminar and methodological master classes that ran in the university nursing school on a monthly basis. These sessions were also made available online so that the clinical nurse researchers could access them at a time that was convenient to them. In addition to this, an annual one day series of workshops and seminars was conducted in order to build on and develop research skills. Based on feedback these talks centred on research dissemination and included talks on how to write an abstract, writing etc. Following the establishment of the research groups the steering group took on the role of monthly monitoring of progress and offering additional support and guidance to the groups and to the post-doctoral researcher in their role as facilitator.

Data collection

There were two minor quantitative measures. Firstly, a survey, with a self-reported research skill utilisation and development questionnaire. This was developed by two members of the steering group. Content and face validity were conducted, it was then piloted by the remainder of the group and an additional three academics. All comments were reviewed, questions rephrased deleted or inserted and reviewed again. The final version surveyed the three main areas in the research process, broken down into 24 separate skills, including, searching and critiquing literature, data collection, cleaning and input and writing and dissemination skills. The nurse researchers reported which aspects of research they were involved in during the intervention and also ranked their perceived skill level/experience pre- and post- intervention implementation on a five point Likert scale from 1: no experience or education in this area, to 5: have significant experience in this area (Additional file 1 : Research skills and activities questionnaire).

The second quantitative measure was an audit of the research outputs arising from the intervention i.e. publications and disseminations (Additional file 1 : Research skills and activities questionnaire).

The major evaluation element was qualitative. It consisted of two focus groups assessing the barriers and benefits of the intervention.

Questionnaires were disseminated to participants by email to those who fulfilled the inclusion criteria approximately 18 Months after implementation of the intervention. The mail content acted as the participant information leaflet and consent was inferred if the participant choose to complete and return the questionnaire. Participants were given the choice to return the questionnaire by email or anonymous copy. The aim of the survey was to give a crude indicator of the aspects of the research process the participants were involved in within the intervention and to assess skill change pre- and post-intervention.

Two focus groups were conducted at around 20 months following implementation of the intervention. The first focus group inclusion criteria were nurse researchers and academics partners who partook in the intervention. The potential participants were emailed inviting them to the focus group. The mail content acted as the participant information leaflet, informing the participant of the voluntary nature of participation, the objectives of the focus group, the manual recording of the discussion, the confidentiality of the process and the fact that the content of the discussion would be disseminated. In a similar manner, members of the steering group were invited to attend a second focus group. The focus groups were facilitated by an experienced facilitator who was a member of the steering committee with the assistance of a note-taker. Consent was taken at the beginning of the focus group. To assist in protecting confidentiality the names of attendees or names mentioned in the focus groups were not recorded. A Strength-Weakness-Opportunity-Threat (SWOT) approach was adopted to guide the conduct of both focus groups. After each focus group notes were written up for analysis.

Finally, the participants of intervention, reported to the steering group detailed information pertaining to their successful outputs. The outputs were then collated and summarised. The outputs presented here are those completed up to December 2015.

Data analysis

The questionnaire data were collated, then anonymised and analysed using SPSS (v21). They were analysed at the descriptive level using frequencies and percentages. Members of the steering committee read and examined the findings to ascertain the quality of the research [ 37 ].

A deductive approach to the analysis of the qualitative data was taken [ 38 ]. Thematic content analysis was carried out using a pre directed or theoretically driven format [ 39 ]. Data from the focus groups were analysed using a SWOT analysis framework. Data were manually coded into strengths, weaknesses, opportunities and threats and subsequently into themes and subthemes. The resulting analysis framework was checked by facilitators to ensure validity of the findings. The analysis was conducted within a realistic perspective which aimed to report experiences, meanings and the reality of the participants [ 39 ].

In line with the first inclusion criteria all nursing staff in advanced nursing roles were invited to partake in the intervention ( n = 72). In line with the second aspect of the inclusion criteria, these invitations asked those with a clinically based research topic of interest they wished to develop or like support with, to volunteer to be part of the intervention. A total of 17 advanced nurses met the eligibility criteria and responded to the initial call. In the first year 12 clinical nurse researchers participated in the intervention. These nurses were all at an advanced level and therefore had qualifications up to masters’ level.

The research groups emerged across many different disciplines within the hospital and included projects in the following fields: haemophilia, tracheostomy safety, Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV) and oncology. It covered areas such as; developing research questions and data collection tools; completing ethics applications; collecting data; developing research questions for data already collected; bringing research previously undertaken to publication; developing and evaluating innovations and implementing and evaluating guidelines. Projects took on average up to two years to complete. Since 2011, an additional two to three new projects are undertaken each year. Currently there are 15 active projects being undertaken.

Self-reported research skill utilisation and development

Seven of the 12 clinical nurse researches from the groups completed evaluation questionnaires, a response rate of 58%. Self-reported research skill level was relativity high (>3 on a scale of 1-5), prior to the intervention in most areas examined, with the exception of data cleaning and writing the background for a paper (Table 2 ). The most common research activities the clinical nurse researchers participated in during the course of the intervention were writing conference abstracts ( n = 6, 86%) and reviewing drafts of their projects’ paper ( n = 5, 71%) (Table 2 ). The greatest skill change occurred in data cleaning. Moderate skill changes were seen in, setting up databases, cleaning data, data analysis, writing background of paper, writing methodology, writing discussion, creating tables and presenting at an external conference (Table 2 ).

Focus group findings

There were five clinical nurse researcher attendees and two academics at the first focus group and six attendees at the steering group focus group. The emerging themes from the two focus groups were drawn together under two overarching themes: 1) strengths and opportunities and 2) weaknesses and threats.

Theme 1: Strengths and opportunities

Within this theme two sub-themes emerged – partnership and outcomes.

Subtheme 1a Partnership

This was a strength identified by both focus groups. The main categories that emerged under this subtheme were teamwork, support, collaboration and goal setting (Table 3 ). Participants felt teamwork was productive and comfortable and it provided support for all participants, in particular there was praise for the support of the post-doctoral research fellow.

“ Couldn’t have done it on my own ”

A further strength of the intervention was the opportunity to collaborate in new ways, as partners, merging expertise to enable the practice research to be completed and showcased. Deadlines set by the project groups themselves emerged as a strength that incentivised work and pushed group members to achieve deadlines for their research tasks within an already busy schedule.

Subtheme 1b Outcomes

Under the outcomes subtheme several categories emerged, namely, publications, skill development, role development, and impact. The number of publications and the multiple dissemination methods used to promote the nursing research profile of the hospital site were identified. Several participants commented on how the intervention offered the stimulus, motivation, opportunity and support to publish findings from previously completed and unpublished research untaken as part of a Master’s degree.

“Means/forum to get the research findings out there”

Participants also highlighted how the innovation facilitated the opportunity to work and develop a variety of research skills. These included methodology knowledge and utilisation, writing and reviewing work, the submission process and developing further research questions. They also reported developing their time management skills.

Clinical impact emerged as an outcome of the innovation. Participants expressed how their involvement in the innovation increased their observation of their own clinical practice, brought the research back to practice, enhanced practice development and the clinical role overall while contributing to improved patient care.

“Not just writing around (theory) – kept bringing it back to practice” “Brought the innovations (practice development) to another level”

Participants also noted that the innovation enhanced the nursing research image both within the hospital and externally.

Theme 2: Weaknesses and threats

Several subthemes emerged from this theme. These were time, awareness of what research involved and general concerns (Table 3 ).

Subtheme 2a Time

Time was a significant barrier to participation in the innovation and this was cited by both the steering committee and the researchers. Specific aspects with regard to time included, making time to do the research, making time for meetings and lack of protected time for research.

“Put under pressure, when no protected time at work”

This was further compounded by the lack of awareness with regard to the amount of time research takes, particularly the unseen elements such as cleaning data, ethics submission process and article submission and resubmission process.

Subtheme 2b Awareness

An important aspect of the innovation that arose from the focus groups was the need to increase awareness across the hospital of staff involvement in research and recognition that this was part of their work.

“Colleagues felt I was removed, spent a lot of time on it (research) ”

The voluntary participation of academic nurse researchers or clinical nurse researchers was seen as a weakness. It also emerged that the value of the intervention in the long term would be threatened if workload, equality and awareness were not addressed within the hospital.

Subtheme 2c General concerns

Academics were matched to projects from either a topic of interest or a methodology expertise point of view but not always both. This was cited as a weakness. Related to this some teamwork was not always optimal, and in some cases lack of clarity of dates, roles and tasks led to frustration and loss of time.

“Wasn’t always clear of the submission date (to team) ”

Awareness of the ethical issues of research including ownership also emerged as threats. Data extraction from retrospective data proved more time consuming than expected and in some instances valuable data was available but the original data collection methods made data extraction impossible from a time point of view. Lack of access to resources like statistical packages within the wards of the hospital proved frustrating and contributed to the missed opportunity for further statistical and analytical skill development of the clinical nurse researchers. In addition, participants experienced frustration, worry and fear that they may be conducting research which may not be published.

Audit of research output metrics

These outputs included six peer reviewed papers, two non-peer reviewed papers, ten international conference presentations, seven national conference presentations and three local conference presentations (Table 4 ).

The social context of advanced nursing in Ireland and internationally dictated a change in research involvement for newly created and growing advanced nursing roles. However, within the local context, the fact that a research culture was not embedded in the site did cause issues in the implementation of this change as seen in previous literature [ 8 ]. This intervention was put in place to address some of these issues by developing a supportive nurse-led research intervention. This intervention proved successful in increasing research capacity and research output of clinical nurses with a research competency attributed to their role.

The intervention developed was a mixed internal and external solution to an identified need of more support for research for advanced clinical nurses with research as part of their role.

The intervention is adaptable and was tailored to the resources and needs of the hospital. The design of the intervention is evidenced based, informed by both the known barriers to research participation by clinical staff and the facilitators to research participation. As indicated in the background there was previous evidence of the strength and quality of some of the different elements within the intervention but an additional strength was the collective use of several of these elements. One of the key strengths of this intervention as recognised in the evaluation and highlighted in previous interventions, was the ongoing support of the Director of Nursing and leadership provided by the steering committee who met monthly [ 8 , 18 ]. The intervention facilitated the development of research expertise, it was close to practice, substantiated the linkages with the university, facilitated collaboration between practice and the university, provided access to educational opportunities and utilised already established resources.

This study supports the previous literature in the area, indicating that a partnership – peer mentorship model, that included a clinical nurse researcher in practice, a nurse or healthcare academic and a post-doctoral research facilitator supported by a high level steering group, improved research output [ 4 , 8 , 12 , 20 , 26 , 30 , 31 ]. An increase in research capacity was also demonstrated from both the quantitative survey of outputs and the focus groups. Supporting previous findings, the main benefits and strengths emerging from the intervention were its promptness to complete research, the chance to publish and showcase innovations and the opportunity to collaborate [ 8 , 11 , 25 , 28 , 30 ]. This was evident not only in the focus group findings but is also supported by the number, range and quality of the disseminations from the audit of publications.

However, several challenges and barriers remained. All of the participants had masters’ level qualifications and had previously partaken in short quantitative analysis courses and methodological classes were available within the intervention. Despite this, the questionnaire results indicated that participation in and the advancement of analytical skills was low. In addition within the qualitative findings, like other studies, nurses were still keen to receive even more input on skills such as statistical and analytical skill development [ 17 ]. The focus groups gave a clear message that time was a major issue, and elements such as data cleaning took a lot of time. Although it would be desirable that advanced clinical nurses were statistically well educated which would enhance the quality of the research experience and the outputs from the research, is it the best use of their time to engage in data cleaning etc.? The intervention developed here was similar to the research model adopted in many parts in academia where the roles are divided. For future development of the intervention we have to work out what is most time effective.

Resources are always an issue for nursing research [ 8 – 13 ]. This externally financed intervention reduced the time needed for research by providing statistical and analysis resources and academic support. The funding for the intervention is sourced like research funding. The post-doctoral researcher position is not funded from central hospital sources but has to be secured externally annually or biannually. This begs the question of the vulnerability of the intervention without this support and does it have enough elements of sustainability and continuity without it? It is envisaged that because of the collaborative links formed with the affiliated academic institute and the increased skills of the participants to date, that the intervention would be able to continue but to a limited extent. The drive and motivation that is offered via the link to the academics and post-doctoral researcher would be missed. Other advanced nurses who have not to date been involved in the intervention may lose out, the work involved in developing research would be a greater challenge and burden.

The proportion of nurses in advanced roles that had a research question ready and were able to partake in the intervention was low (17%), which needs to be explored further to see what individual or local context barriers remain an issue to participation in research. This is a weakness as it may prevent the development of a culture of research development within the site [ 13 , 25 , 27 , 31 ]. Although the intervention facilitated the successful attainment of competencies there was no incentive except personal, for publication. The implementation did provide an ideal microclimate for learning and development. Of those who did participate, in support of previous literature, this study found allocating time for research was still an ongoing challenge [ 5 , 8 , 9 , 11 , 12 , 18 , 19 ]. It is still difficult for research to be seen as a priority given clinical commitments in spite of supports at senior level. Having protected time for research may help address this issue. While there was a perceived need for the implementation of this intervention, the timing of the implementation was far from perfect. It occurred at a time when there was an embargo within the hospital on staff recruitment so staff were stretched to fulfil the direct patient centred competencies of their role never mind their research and audit competencies, therefore these could not be prioritised.

Another contributing factor to poor uptake and previously documented as a barrier to research may be the lack of awareness of the intervention across the hospital [ 8 , 25 ]. Increasing awareness and visibility of the intervention and the support from the senior ward staff should further assist in nurses spending time at research without causing animosity from colleagues. The time has come to further develop the intervention. This could be achieved by consideration of getting more permanent funding for the intervention, providing protected time for research and increasing the research role visibility as a non-optional aspect of the advanced clinical nurse role. The establishment of this intervention as a permanent feature will be threatened if funding, workload, equity and awareness are not addressed.

Conclusions