An official website of the United States government

Official websites use .gov A .gov website belongs to an official government organization in the United States.

Secure .gov websites use HTTPS A lock ( Lock Locked padlock icon ) or https:// means you've safely connected to the .gov website. Share sensitive information only on official, secure websites.

- Publications

- Account settings

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

What is community engagement and how can it drive malaria elimination? Case studies and stakeholder interviews

Kimberly baltzell, kelly harvard, marguerite hanley, roly gosling, ingrid chen.

- Author information

- Article notes

- Copyright and License information

Corresponding author.

Received 2019 Apr 14; Accepted 2019 Jul 9; Collection date 2019.

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License ( http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ ), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver ( http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/ ) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

In light of increasing complexity of identifying and treating malaria cases in low transmission settings, operational solutions are needed to increase effective delivery of interventions. Community engagement (CE) is at the forefront of this conversation given the shift toward creating local and site-specific solutions. Malaria programmes often confuse CE with providing information to the community or implementing community-based interventions. This study seeks to expand on CE approaches for malaria by looking to a variety of health and development programmes for lessons that can be applied to malaria elimination.

Qualitative data was collected from key informant interviews and community-based focus group discussions. Manual analysis was conducted with a focus on key principles, programme successes and challenges, the operational framework, and any applicable results.

Ten programmes were included in the analysis: Ebola, HIV/Hepatitis C, Guinea worm, malaria, nutrition, and water, sanitation and hygiene. Seven focus group discussions (FGDs) with 69 participants, 49 key informant (KI) interviews with programme staff, and 7 KI interviews with thought leaders were conducted between October–April 2018. Participants discussed the critical role that village leaders and community health workers play in CE. Many programmes stated understanding community priorities is key for CE and that CE should be proactive and iterative. A major theme was prioritizing bi-directional interpersonal communication led by local community health workers. Programmes reported that measuring CE is difficult, particularly since CE is ongoing and fluid.

Conclusions

Results overwhelmingly suggest that CE must be an iterative process that relies on early involvement, frequent feedback and active community participation to be successful. Empowering districts and communities in planning and executing community-based interventions is necessary. Communities affected by the disease will ultimately achieve malaria elimination. For this to happen, the community itself must define, believe in, and commit to strategies to interrupt transmission.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1186/s12936-019-2878-8) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Community engagement, Malaria elimination, Community participation, Local leadership, Community buy-in, Community implementation

Between 2000 and 2015, 17 countries successfully eliminated malaria and an additional 10 countries are expected to eliminate by 2020 [ 1 ]. Based on this success, malaria eradication is being explored as a feasible global goal. Despite initial momentum, however, progress has stalled and actually regressed in some countries, primarily in the WHO African Region [ 2 ]. Funding for malaria control and elimination has remained relatively stable over the past 2 years, as have reported cases at approximately 219 million cases of malaria in 2017 [ 2 ]. In countries that have successfully decreased their malaria burden, cases often start to cluster in smaller geographic foci and among subpopulations with unique risk characteristics [ 3 , 4 ]. Current interventions, including insecticide-treated bed nets, indoor residual spraying (IRS), and community case management are effective only if they are accessible, acceptable, and properly used within communities. Many of the challenges to malaria elimination are site specific and require a more tailored approach to effectively target these remaining foci of transmission and populations at higher risk.

In light of stalled progress, flatlined funding [ 2 ], and the increasing complexity of identifying and treating malaria cases, the global community is looking to operational solutions to increase the effective delivery of interventions for malaria. The topic of community engagement is at the forefront of this conversation and is recognized as an essential component in the shift toward creating local and site-specific solutions. Community engagement strategies have long been incorporated into themes such as women’s health, political action, and HIV [ 5 ]. Community engagement is often confused with simply providing information, education, and communication (IEC) to the community; the malaria community have only recently begun to consider the significance and potential of community engagement for malaria elimination [ 6 – 9 ].

Achieving effective community engagement in malaria will be a major challenge since most elimination settings must grapple with heterogeneous transmission, often concentrated in hard to access locations and/or among marginalized population groups [ 3 ], as well as changes in perceptions of personal risk and community-level health priorities [ 7 ]. Malaria control and elimination programmes often employ standard community-based activities for malaria including the use of community health workers or volunteers (CHWs) to conduct case management, surveillance, vector control, and information, education and communication (IEC) activities and social behaviour change communication (SBCC). This study seeks to expand on potential community engagement approaches for malaria by looking to lessons from a variety of health and development programmes.

There is great potential to improve community engagement for malaria elimination. It is possible that other health and development sectors can help to inform a paradigm shift in how malaria programmes incorporate affected communities in interventions. This series of case studies aims to capture the experience of community engagement across a range of health and development sectors to explore how malaria and other programmes use community engagement strategies to design, implement, monitor, and sustain interventions.

This qualitative study used key informant (KI) interviews and focus group discussions (FGDs) to explore approaches to community engagement in malaria elimination efforts as well as other sectors. Programmes from eight health and development sectors, including malaria, were identified for programmatic evaluation. Specifically, the study explores community engagement perceptions and practices at three levels; from thought leaders (defined as those with expertise or leadership positions in sectors included in the study) who design CE activities, from programmatic staff who manage and implement community engagement activities, and from community members involved in community engagement interventions.

Participants were identified from within the researchers’ network and/or snowball sampling. Individuals were contacted through email to ask if they might be a suitable participant in the study; could provide contact information for other individuals with relevant contacts; and could provide contact information for other potential participants. Through this process, relevant and accessible individuals and institutions with current or prior experience working on community engagement programs were identified.

Programme inclusion/exclusion criteria

Programmes selected for inclusion met the following criteria: (1) from priority health and development sectors identified by the research team; (2) represent a varied selection of sectors and institution-types; (3) contain an intentionally designed community engagement strategy; (4) perceived by colleagues and/or programme staff as successfully mobilizing community action, and/or having taken a creative, bottom-up approach to engaging the community; (5) from geographically diverse locations; and (6) KIs representing the programme were able to be identified through the research team networks. Programmes that did not address health or development issues and those which did not employ community engagement activities were excluded from consideration.

Thought leaders

Thought leaders were interviewed using a semi-structured interview guide (Additional file 1 ) designed to explore the role that community engagement has played across different health and development sectors, and to establish similarities and differences in approaches to community engagement practices. The term “thought leader” is described as those who possess social capital, have respect and influence among colleagues, and can influence others [ 10 ].

Inclusion criteria for thought leaders included in this study are: (1) ≥ 5 years in a senior-level position within the health and development sector; (2) previously involved or currently involved in community engagement strategy and design; (3) ≥ 18 years of age; (4) fluency in English; and (5) willing to provide written informed consent. Interviews were conducted in-person when feasible, and by Skype or phone when travel by the research team was not feasible. When available, a note taker was present, and interviews were audio recorded when permission from the key informant was granted. Written consent from the interviewee was obtained prior to the start of the interview and interviews took no longer than 60 min. Individuals were excluded if they are unable or unwilling to provide informed consent.

Programme staff

For each programme, between two and eight programme staff were interviewed following a semi-structured interview guide. Samples questions focused on programme objectives, measurements of success, sources of guidance, and both explicit and perceived definitions of community engagement (Table 1 ). Interviews focused on the community engagement strategies employed including the design process; operational, financial and human resource requirements; key elements; lessons learned and any available results; as well as the contextual factors that may have positively or negatively impacted the programme.

Constructs and sample questions from key informant interview guides

Programme staff selected for key informant interviews met the following criteria: (1) ≥ 6 months organizational experience with the ability to discuss at length the selected community engagement programme including the design process, key elements, operational framework, financial and human resource requirements, and/or results; (2) involved in the community engagement strategy design, implementation and/or assessment; (3) employed in the organization of the selected community engagement effort within the past 3 years and has organizational permission to discussion the programme; (4) ≥ 18 years of age; (5) fluency in English; and (6) willing to provide written informed consent. Paid community health workers were also considered programme staff for purposes of this study and these interviews were conducted with the corresponding interview guide.

Community members

In collaboration with the participating programmes, FGDs with individuals residing in the programme catchment areas were conducted. Participating programme staff and community leaders assisted in the identification of focus group participants; purposive sampling and/or snowball sampling was used when necessary. Focus group participants were identified based on their place of residence during programme implementation, as well as their willingness to participate. An attempt was made to ensure that both men and women were included in each FGD.

Focus group discussions sought to obtain the community’s perception of programme activities and outcomes to examine motivators and impediments to community engagement. A semi-structured interview guide was used to frame the discussions and all FGDs were conducted in-person during field visits by a member of the research team. Questions focused on the meaning of community engagement, impressions of past experience with community engagement strategies, and how future efforts could be improved (Table 2 ).

Constructs and sample questions from community focus group discussions

Participants selected for FGDs met the following criteria: (1) familiarity with the selected community engagement programme, (2) resided in the programme catchment area at the time of implementation of the community engagement strategies, (3) ≥ 18 years of age, and (4) willing to provide written informed consent. Unpaid community health workers were considered community members for the purposes of this study. When English was not the native language of participants, a local translator was used. Focus group discussions took no longer than 90 min. Light refreshments were offered to FGD participants. Individuals were excluded if they were unable or unwilling to provide informed consent.

Data analysis

After each interview or FGD, the interviewer recorded themes, general comments, and additional observations. Audio-recordings were not transcribed word-for-word. Instead, after each interview or FGD, detailed notes were recorded, and a discussion of themes and observations occurred between the interviewer and note-taker when a note-taker was present. After the interview or FGD, notes were uploaded into Microsoft Word (2010). The data were manually analysed to obtain a greater depth of knowledge on the health and development programmes profiled, with a focus on key principles, the programme successes and challenges, lessons learned, the operational framework, and any applicable results.

Overall, ten programmes with community engagement strategies from seven different health focus areas were included in the analysis: Ebola, HIV/Hepatitis C, Guinea worm, malaria, nutrition, and water, sanitation, and hygiene (WASH) (Table 3 ). Seven focus group discussions (FGDs) with 69 participants, 49 key informant interviews with programme staff, and seven key informant interviews with thought leaders were conducted between October 2017 and April 2018. Four of the ten programmes focus on disease elimination and eradication (The Carter Center, Isdell:Flowers, PATH MACEPA, and MORU).

Programmes included in analysis and level of engagement

FGDs focus group discussions, GAIA Global AIDS Interfaith Alliance, HIV human immunodeficiency virus, MORU the Mahidol Oxford Tropical Medicine Research Unit, NGO non-governmental organization, NTDs neglected tropical diseases, PATH MACEPA PATH’s Malaria Control and Elimination Partnership in Africa, TREAT Asia/amfAR Therapeutics Research, Education, and AIDS Training in Asia/American Foundation for AIDS Research

Key stakeholders to include in the design and implementation of community engagement process

Programmes included in this study reported targeting and working with a range of stakeholders on community engagement including: local and religious leaders, nurses and community health workers (CHWs), village councils and other community groups (including women’s groups, youth groups) and teachers and school children. Many of the KI interviews and FGDs centered on the critical role that village leaders and CHWs play in community engagement efforts.

Consultation with and buy-in from community leaders such as village chiefs, pastors, and local healers was noted to be critical by all ten programmes. Several programmes referred to community leaders as “key influencers,” and emphasized that programmes are likely to fail if local leadership does not support the programme’s goals. “[Village leaders are the] gatekeepers in Malawi — you must work with them to understand the cultural factors at play. Their input is invaluable .” (KI participant). It was reported that collaborating with village leaders could often help identify other potential community leaders; particularly CHWs, which many programmes rely on to deliver community engagement and other health services. All programmes that recruited CHWs from the community used local leadership to identify appropriate candidates.

Many of the programmes support the practice of hiring known and trusted community members as CHWS. Programmes also reported leveraging nurses, teachers, community health workers, and targeted peer groups to reach these groups extended networks. Peers include women and mothers, and at least one programme established a men’s group after finding that there was no formal mechanism to engage with this population at the community level. In addition, several groups reported success in developing survivors and/or people living with the disease of focus into CHWs or programme staff/volunteers for greater impact and credibility among those with similar prognoses (e.g. people living with HIV, TB, Ebola survivors).

Working with the Ministry of Health (MoH) was cited as critical by most programmes; however, it was also noted that MoH priorities can change and there are often competing demands for focus. Several programmes pointed to the importance of partnering with district health authorities. Doing work beyond the primary health focus (e.g. providing school fees and/or uniforms for orphans, providing family planning or child vaccination services) was described by several programmes, indicating the value of a multi-sectoral approach to community engagement.

Ensuring buy-in

Many of the programmes in this project use creative and socially-based approaches to advance engagement. Utilizing multiple channels of communication were cited as important. Examples of channels used by the programmes in this study include the use of soccer clubs, films, community drama, television, songs, Facebook, social events such as weddings, discos, and community fairs with prizes. Children were repeatedly mentioned as important change agents and it was recommended that youth groups be mobilized to assist with messaging: “ kids are the channel to the homes .” (KI participant). One programme was having difficulty obtaining community buy-in so they expanded outreach into schools where they were able to successfully engage parents by sharing programme goals and messaging with students.

As a mechanism for representing collective stakeholder interests and showing neutrality, Belize Red Cross brought together groups of local residents (30–40 people) to do mapping exercises around water sources. Activities that involve everyone and do not have a political or religious agenda were deemed important in this setting; however, using religious leaders for messaging was cited as valuable in other contexts. Several programmes reported that providing malaria messaging at church was a particularly useful strategy and one KI cited the power of having the local pastor take his anti-malarial medicine during his sermon. In areas where mobile technology is readily available, it was used by some programmes to engage the community; this included using apps to report cases or disseminate information, education and communication (IEC) materials.

One thought leader cautioned that community priorities may not be the same as the programme priorities and three programmes recommended openly identifying and acknowledging competing priorities in discussions with community stakeholders. Kore Timoun asks communities to apply for help with their locally identified needs and if they align with Kore Timoun’s mission and capacity, a partnership is formed. Four programmes reported that incorporating community-identified or acute health priorities into the primary programme was found to be useful. In fact, several of the organizations profiled here started with a specific health or development focus and expanded to other content areas after infrastructure was in place and the community was familiar with the work of the organization. A striking example is Wellbody Alliance, which initially started with the goal of providing primary care. In order to deliver high-quality primary care, Wellbody ran community-based HIV, TB, maternal, and child health programmes. During the 2014–2016 Ebola outbreak in Sierra Leone, the existing community health worker infrastructure and organization’s approach to community engagement was leveraged to rapidly develop community-based Ebola virus disease surveillance programmes.

One of Wellbody Alliance’s major learnings from the Ebola outbreak was the power of bi-directional, interpersonal communication led by local CHWs, and other programmes profiled in the study echoed this. Community meetings are popular venues for community engagement and were cited by six of the programmes. Other popular group activities include drama and music performances, art shows, and school-based activities. Door-to-door engagement with the local community was cited as being very effective by programmes using the technique; one programme reported targeting home visits to community members that often miss larger events or to individuals who seem hesitant or unwilling to participate. In these instances, discussions center on specific concerns, perceptions, or challenges to participation. Similarly, to engage with more people, the majority of programmes suggested that the timing of programme activities should accommodate various work and holiday schedules. Several programmes noted that when interventions or education sessions are only offered Monday through Friday during the day, community members who work or travel are often missed.

Among the programmes included in this study, there was variation in approaches to increasing community motivation. Several programmes use reward systems and several use community members to identify those who do not participate or are chronically missed by existing interventions. One programme provides cash rewards to those who reported a suspected case of disease (The Carter Center), while others use prizes to recognize community members (GAIA). Another programme (Belize Red Cross) created a cleanup campaign, which received formal recognition from the local Department of Environment for providing the community with the most improvement in hygiene; programme staff and community members stated that the community remains clean today.

TREAT Asia, an organization focused on HIV and co-infections including Hepatitis C, reported that harnessing the anger at being marginalized based on health status was key to the success of their work. They stated that those infected are highly motivated to advocate for others affected by HIV. To reduce stigma, several programmes use harmonization with programmes targeting other health and development areas; for example, asking “how does HIV affect agriculture?” delivers messaging without segregating a specific group. Three programmes also reported that positive messaging was almost always more effective than scare tactics. Kore Timoun bases its community engagement approach on the positive deviance model, which identifies individuals in the community who face the same socioeconomic and cultural conditions as peers but have established personal practices that keep themselves and/or family members healthy. These individuals are then empowered to share their successful practices with other members of the community [ 11 ].

The majority of the programmes included in this report acknowledged that understanding community priorities is key. Most programmes’ goals include moving communities from focusing on treatment to prevention. However, the first step in achieving this shift is to work with local leaders to confirm that the programme priority is among the community’s main concerns. “ Villages have their own priorities, and most people need to see some self - interest in taking up additional activities .” (Thought leader). Regardless of the specific approach or activity, there is general consensus that collaborating with the community is essential, especially as a means to promote community ownership and sustainability of the health or development programme. Treating the community as a partner was a common theme.

Community engagement needs to be a proactive and iterative process

Seven of the programmes reported that community engagement should be proactive and iterative. Most KIs were in agreement that for community engagement to be effective, it should be integrated from the start and should not only be implemented once a problem has been identified. It was noted that communities should have full and transparent information regarding the programme upfront: “ The community must have detailed information on the programmes intentions, goals, timeline, exit strategy… They deserve full transparency, and when they get it they are usually much more engaged. ” (KI participant). Most programmes discussed taking the programme design to the community after it was finalized. However, they suggested it is important to include the community in the initial design of the intervention or programme and then find ways to continually engage stakeholders throughout the process.

Participants described CE as a “learning process,” and strongly advocated that the community engagement efforts be responsive to the changing perceptions and needs of the community. “ The nature of community engagement is that it needs to be constantly modified .” (KI participant). Being able to respond to rumors or changing attitudes and perceptions by shifting strategies, activities, and/or targeting and engaging with new or different groups quickly and effectively, was identified as a key factor of successful community engagement programmes. Establishing a transparent feedback loop was also cited as important for community engagement. Similarly, giving community tangible feedback on programme results and milestones was mentioned as vital to keep communities invested. One focus group participant reinforced the importance of continuous communication with the community before, during, and after an intervention. In this programme, providing “complete information” along with consistent messaging, sensitization, and dialogue were key components to keeping the community engaged. This sentiment was echoed by another thought leader who suggested the development of a community engagement task force to lead and facilitate the iterative process.

Challenges with measurement of success

Programmes included in this analysis have a range of goals, from eliminating disease, to creating cadres of community health workers, improving health literacy, and empowering communities. However, many of the programmes reported that measuring community engagement is difficult. While easy to quantify results from surveys and other tools, most programmes said it was difficult to measure which aspects of community engagement are most effective. This was stated as particularly difficult given that community engagement is generally an ongoing and fluid process with no fixed set of strategies. Most programmes in this study proactively engage with communities and continuously adapt as needed. One programme suggested doing resident surveys to assess community satisfaction and sense of ownership. Another programme used the number of community members seeking HIV testing as a monitoring and evaluation metric—if the number fell below the target, the organization went to the community to find out why and changed engagement strategies once they received feedback.

Some of the strongest evidence of successful community engagement are examples of community-initiated programmes that supported, enhanced, or built upon the original intervention. Similarly, if the community asked for additional services to facilitate participation, this was also seen as a sign of successful community engagement. In the case of GAIA, CHWs continued to do their job even after the programme ended—their feeling of ownership created a sense of responsibility to the community. One programme was contacted by the MoH to train workers, including teachers, in districts outside the original scope of the programme to expand their mission and reach. In one malaria programme, the community independently instituted border screening to prevent constant reintroduction of the disease by a neighbouring country.

Several organizations use traditional metrics to measure success; for example, the number of patient visits to clinics, increased use of bed nets, decrease in number of HIV cases diagnosed, decreased use of traditional healers, reduced number of births due to uptake of family planning, and decrease in number of children diagnosed with malnutrition. In addition, regular stakeholder meetings, satisfaction surveys, and group discussions were listed as ways to gauge the success of community engagement strategies and remind the community that the programme values their input and engagement.

Without exception, all participants in this study agreed that community engagement is vital for long-term success of any intervention or for uptake of new strategies to improve health. This sentiment is echoed in various global technical strategies and resolutions. However, how to operationalize community engagement at scale remains elusive and participants in this study acknowledge that the definition and execution of community engagement varies greatly. The majority of participants included in this study point to some consensus that transformative community engagement is more than providing information to the community, and that communities should be involved in the design and implementation of health interventions. There are some consistent community engagement practices that support a collaborative approach to community engagement and are worth noting by malaria elimination programmes.

First, guidance and support by local leadership before developing a strategy was cited as critical. Community leaders have long been identified as essential to community engagement. Lavery et al. state that it is important to know if the community wants what is offered before setting an agenda [ 5 ]. During the 2014–2016 Ebola outbreak in West Africa, establishing strategic partnerships with community and religious leaders was identified as one of seven key domains for success of the response [ 12 ].

Second, virtually all programmes included in this study rely on CHWs to be the primary point of contact between the organization and the community. CHWs play an important role in community engagement and their presence was identified as necessary to gain community trust and acceptance. To strengthen community buy-in, programmes using CHWs reported that their CHWs are nominated by local leadership and/or through a participatory, community-based election process. A few programmes reported that for CHWs to be truly effective, they must have a consistent presence in the community. In malaria, the disjointed nature of hiring CHWs for short-term or seasonal intervention work may limit their effectiveness. Understanding how to best train and use CHWs in low transmission settings is important for malaria elimination given that CHWs are often the first point of contact for febrile illness [ 13 ]. In Myanmar, expanding the remit of “malaria-only” CHWs to include a broader package of basic health care services has proven effective in sustaining community uptake of malaria services in low transmission areas of the country [ 14 ]. Additionally, having established CHWs within the community prior to malaria or other infectious disease outbreaks may prove invaluable during response measures, as it was for Wellbody Alliance during the Ebola epidemic in Sierra Leone. Mobilizing adequate human resources to support the community engagement is important but is only one piece of a larger process [ 15 ]. A recent systematic review shows investing in CHWs performance may result in improved behavioural outcomes for patients and an increase in the number of patients seeking care, important aspects of malaria elimination. Practices and interventions noted to improve CHW performance include (1) emphasizing personal career growth; (2) encouraging CHW supervisors to remind CHWs of tasks and hold accountable those who are underperforming; (3) creating proper incentives based on responsibilities of the CHW; and (4) using mobile phone technology when available [ 16 ]. While CHWs were identified as enabling community engagement, it is important not to conflate CHW programmes with community engagement.

Third, is the importance of bidirectional communication. Research often focuses on increasing the number of participants in a study, usually through sensitization. This is a unidirectional process, delivering messaging after an intervention has been decided upon. While sensitization has been shown to result in improved uptake during a research study or clinical trial [ 17 ], health interventions or strategies that remain in the community long-term may benefit from bidirectional communication. In fact, bidirectional learning was identified as a key component in interventions where population health and/or health behaviour improved [ 18 ]. The “community dialogue” approach offers one possible mechanism for strengthening community engagement and uptake of health services [ 19 ]. Study results and recent literature indicate that home-based visits to discuss individual and/or household-level concerns related to acceptance and uptake of interventions may be useful [ 20 , 21 ]. It is relevant to note that all programmes stated that community engagement should be iterative and responsive to changing community needs, perceptions, and opinions. Another likely challenge to malaria elimination activities are community misconceptions and rumors: lessons from polio elimination show the often detrimental power that rumors can exert on disease eradication and elimination programmes [ 22 ]. The importance of ongoing efforts to adapt both programming and messaging based on the specific needs of a community further suggests that community engagement is not a one-size-fits-all strategy.

Fourth, is consideration of the possible disconnect between local residents and the ministry officials making decisions on behalf of the community. In addition, while harmonization across health and development sectors is important to avoid community participation burn-out, harmonization within sectors was noted as important as well; malaria interventions should aim to avoid duplicative efforts with other programmes, and engage with local residents in advance of the start of control or elimination activities. As indicated above, the programmes included in this study reported that obtaining community input into the design itself of the health intervention, prior to implementation, is important. This was cited even among programmes that do not actually practice this, possibly indicating that operationalizing such learning is difficult. A community engagement strategy that is iterative, harmonized, and tailored to the local context is difficult to manage at the national level; since malaria elimination strategies are carried out at the district level, it is fitting that local teams should be empowered to develop, adapt, and implement community engagement strategies.

Finally, given the few number of cases in low malaria transmission settings, it is possible that communities no longer identify malaria as the greatest threat to well-being—a serious challenge to these lessons. In Eswatini, younger members of the community were less likely to have had malaria or to have seen the effects of malaria firsthand, limiting their concern of risk or personal investment in elimination efforts (Baltzell, in press). One of the key informants interviewed reported that moving from primarily curative to preventive services merits careful consideration. Studies show that village-based malaria workers are often more effective at providing diagnosis and treatment than prevention and vector control [ 23 ]. Additionally, in recent targeted malaria elimination pilot studies in the Greater Mekong Sub-region, the health messaging, particularly on the role of asymptomatic infections, is reported as complex and difficult to communicate effectively [ 20 , 21 ].

Study participants acknowledged the difficulty of measuring the impact of community engagement. It was often reported that community engagement is time- and resource-intensive. However, instead of traditional outcomes measures, improved community health may be confirmation enough of community engagement and its importance. Methods cited to evaluate the community engagement process include process evaluations, FGDs, and KAP surveys. Rifkin et al. developed an approach to for assessing engagement based on a continuum of participation [ 24 ]. This tool is adaptable and provides at least one method to evaluate the process of engagement and highlight its links to health outcomes. This evaluation process can be further strengthened by involving community stakeholders in the collection and analysis of data [ 25 ].

One programme reports it is important to critically assess the diversity of those involved in the community engagement process. This is supported by various sets of normative guidance including the Principles of Community Engagement, released by the US Center for Disease Control (CDC) and Agency for Toxic and Substances and Disease Registry (ASTDR), which recommend evaluating the following questions during the M&E process for community engagement [ 26 ]:

Are the right community members at the table?

Does the process and structure of meetings allow for all voices to be heard and equally valued? For example, where do meetings take place, at what time of day or night, and who leads the meetings?

These are especially important considerations for malaria elimination, as those considered to be the “right” community members will shift and evolve as transmission decreases and malaria increasingly affects different and heterogeneous groups and individuals.

In summary, all programmes in this study prioritized community engagement strategies in their work. Overriding principles among the study participants include listening to the voice of the community and its leaders prior to study/intervention design and not simply offering sensitization during or after implementation; expanding the use and training of community members to help with programme delivery (e.g., CHWs); and making sure that community engagement is an ongoing and iterative process. One key informant described community engagement as an “art”. It might also be considered a programme management issue. To improve implementation, community engagement should be delivered and managed sub-nationally. It should be moved out of isolation within programmes, harmonized with other health programmes, and embedded within local health priorities. When appropriate, malaria elimination programmes should consider closer coordination with other health and development sectors; focusing messaging on prevention versus treatment and the importance of testing in the absence of symptoms; and contributing to the development of a permanent, cohesive team of CHWs and/or a community engagement task force to assist with sustainability of multiple health programmes. In particular, malaria elimination settings may be hindered by a perception of no risk among populations where cases are few. Given this scenario, community engagement will take on added importance to make sure that communities themselves have the capacity and resources to lead sustainable, effective measures to reduce and eventually eliminate malaria transmission.

Limitations

All successful elements of community engagement reported here are self-reported and the study team did not independently assess impact. While this study was comprehensive in the scope of programmes and stakeholders, purposive sampling was used to identify participants and this may have influenced results. In addition, focus group discussions and KI interviews were not transcribed word for word; the analysis was based on summaries written by the interviewing field team. This limited the authors’ ability to illustrate findings with verbatim quotes or messaging. Lastly, only academic institutions and NGOs were included among the participating programmes. However, despite these limitations, study findings align with much of the literature on the topic of community engagement.

Evidence from the case studies overwhelmingly suggests that community engagement must be an iterative process that relies on early involvement, frequent feedback, and active participation from the community to be successful. While there are other papers that explore the role of community engagement in malaria elimination, this study offers several conclusions to expand on that exploration.

First, strengthening other complementary health programmes is likely to improve community engagement and community participation, a prime example being improving CHW programs and incorporating community engagement best practices, such as involving the community in the CHW recruitment process. Many of these strategies and policy documents are already endorsed by WHO and its country partners; it is important to begin to prioritize the practical implementation of these strategies and policies more broadly.

Second, much of the necessary infrastructure (i.e. CHW programmes) and processes (i.e. community dialogue and other deliberative processes) exist but likely require quality improvement interventions. The processes and accountability mechanisms for involving communities in decision making should be built into programmes prior to implementation. To make this shift, malaria programmes will need support from specialists in participatory methodology and community engagement, amongst others. The good news is that such expertise exists, as demonstrated in this paper.

Third, is that in order for community engagement to be an iterative process that relies on early involvement, frequent feedback, and active participation from the community, malaria programmes will need to empower districts and communities to become involved in planning and executing community-based interventions. Units closer to the level of implementation should be better equipped and empowered to lead community engagement efforts. This would be a departure from how many national malaria programs operate today. This shift would not only instill the operational nimbleness required for community engagement but would also promote the implementation of locally tailored and targeted case management, vector control, and surveillance interventions.

Malaria elimination will ultimately be achieved by the communities affected by the disease; for this to happen, the community itself must define, believe in, and commit to strategies to interrupt transmission.

Additional file

Additional file 1. Questionnaire and interviewer guide: thought leader interviews from different health and development sectors .

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to express thanks to the following people, organizations and communities for participating in this study and for helping to shape our understanding of the varied approaches to community engagement:

Susan Lassen, Rebecca Vander Meulen, Alexandra Gordon, Constance Njovu, Monica Mvula, Vivian Mwaba, Mutenda Sitakwa, Isaac Ndhlovu, and the Isdell:Flowers Cross Border Malaria team and community partners; Moriah McArthur, Rose Elene Veillard, Metichael Vilus, Leonie Barreau, and the Kore Timoun team and community partners; Bailor Barrie, J. Daniel Kelly, Fodei Daboh, Kumba Tekuyama, and the Wellbody team and community partners; Ellen Schell, Joyce Jere, Annie Seuani, Kondwani Kanjelo, Nelson Khozomba, and the GAIA team and community partners; Giten Khwairakpam, Jeremy Ross, Annette Sohn, and the TREAT Asia team and community partners; Lily Bowman, Fred Hunter, Jessie Young, Charletta Casanova, and the Belize Red Cross and community partners; Angelia Sanders, Kelly Callahan, Ernesto Ruiz-Tibin, and the Guinea Worm Eradication Program team at The Carter Center; Todd Jennings (PATH MACEPA); Bipin Adhikari (MORU); Jaime Sepulveda (UCSF Global Health Institute).

Abbreviations

Agency for Toxic and Substances and Disease Registry

Center for Disease Control

community health workers or volunteers

focus group discussions

indoor residual spraying

information, education, and communication

key informant

Ministry of Health

social behaviour change communication

water, sanitation, and hygiene

Authors’ contributions

KB designed the study, assisted with data analysis and final manuscript writing. KH designed the study, assisted with data analysis and final manuscript writing. MH conducted interviews and FGDs and assisted with manuscript editing and revision, RG initiated the study concept and assisted with manuscript editing and revision, IC led the initial study strategy and assisted with manuscript editing and revision. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

The funding for this project was obtained from the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation OPP 1160129.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets/transcript briefs analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The research protocol was reviewed and approved by the Human Research Protection Program Institutional Review Board (IRB) of the University of California San Francisco (17-22884).

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

- 1. WHO. World Malaria Report 2016. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2018. http://www.who.int/malaria/publications/world-malaria-report-2016/report/en/ . Accessed 3 Jul 2017.

- 2. WHO. World Malaria Report 2018. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2018. http://www.who.int/malaria/publications/world-malaria-report-2018/report/en/ . Accessed 3 Jul 2017.

- 3. Cotter C, Sturrock HJW, Hsiang MS, Liu J, Phillips AA, Hwang J, et al. The changing epidemiology of malaria elimination: new strategies for new challenges. Lancet. 2013;382:900–911. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)60310-4. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 4. Bousema T, Griffin JT, Sauerwein RW, Smith DL, Churcher TS, Takken W, et al. Hitting hotspots: spatial targeting of malaria for control and elimination. PLoS Med. 2012;9:e1001165. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001165. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 5. Lavery JV, Tinadana PO, Scott TW, Harrington LC, Ramsey JM, Ytuarte-Nuñez C, et al. Towards a framework for community engagement in global health research. Trends Parasitol. 2010;26:279–283. doi: 10.1016/j.pt.2010.02.009. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 6. Atkinson J-A, Vallely A, Fitzgerald L, Whittaker M, Tanner M. The architecture and effect of participation: a systematic review of community participation for communicable disease control and elimination. Implications for malaria elimination. Malar J. 2011;10:225. doi: 10.1186/1475-2875-10-225. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 7. Whittaker M, Smith C. Reimagining malaria: five reasons to strengthen community engagement in the lead up to malaria elimination. Malar J. 2015;14:410. doi: 10.1186/s12936-015-0931-9. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 8. WHO. Global health experts define malaria work packages. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2017. http://www.who.int/malaria/news/2017/second-meeting-sag-malaria-eradication/en/ Accessed 13 Feb 2019.

- 9. Opinion: Civil society and community engagement key to achieve malaria elimination. Devex. 2018. https://www.devex.com/news/sponsored/opinion-civil-society-and-community-engagement-key-to-achieve-malaria-elimination-93801 . Accessed 13 Feb 2019.

- 10. White M. Book Review: knowledge management lessons learned. Ariadne Web Mag Inf Prof. 2004. http://www.ariadne.ac.uk/issue/41/white-rvw/ . Accessed 24 June 2019.

- 11. Children’s Nutritional Program of Haiti: Positive Deviate Hearth. https://www.cnphaiti.org/positive-deviance-hearth/ . Accessed 13 Dec 2018.

- 12. Gillespie AM, Obregon R, El Asawi R, Richey C, Manoncourt E, Joshi K, et al. Social mobilization and community engagement central to the Ebola response in West Africa: lessons for future public health emergencies. Glob Health Sci Pract. 2016;4:626–646. doi: 10.9745/GHSP-D-16-00226. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 13. Mazzi M, Bajunirwe F, Aheebwe E, Nuwamanya S, Bagenda FN. Proximity to a community health worker is associated with utilization of malaria treatment services in the community among under-five children: a cross-sectional study in rural Uganda. Int Health. 2019;11:143–149. doi: 10.1093/inthealth/ihy069. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 14. McLean ARD, Wai HP, Thu AM, Khant ZS, Indrasuta C, Ashley EA, et al. Malaria elimination in remote communities requires integration of malaria control activities into general health care: an observational study and interrupted time series analysis in Myanmar. BMC Med. 2018;16:183. doi: 10.1186/s12916-018-1172-x. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 15. Adhikari B, James N, Newby G, von Seidlein L, White NJ, Day NPJ, et al. Community engagement and population coverage in mass anti-malarial administrations: a systematic literature review. Malar J. 2016;15:523. doi: 10.1186/s12936-016-1593-y. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 16. Ballard M, Montgomery P. Systematic review of interventions for improving the performance of community health workers in low-income and middle-income countries. BMJ Open. 2017;7:e014216. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2016-014216. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 17. Dierickx S, O’Neill S, Gryseels C, Immaculate Anyango E, Bannister-Tyrrell M, Okebe J, et al. Community sensitization and decision-making for trial participation: a mixed-methods study from The Gambia. Dev World Bioeth. 2018;18:406–419. doi: 10.1111/dewb.12160. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 18. Cyril S, Smith BJ, Possamai-Inesedy A, Renzaho AMN. Exploring the role of community engagement in improving the health of disadvantaged populations: a systematic review. Glob Health Action. 2015;8:29842. doi: 10.3402/gha.v8.29842. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 19. Community dialogues for child health results from a qualitative process evaluation in three countries. J Health Popul Nutr. 2017;36:29. doi: 10.1186/s41043-017-0106-0. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 20. Adhikari B, Pell C, Phommasone K, Soundala X, Kommarasy P, Pongvongsa T, et al. Elements of effective community engagement: lessons from a targeted malaria elimination study in Lao PDR (Laos) Glob Health Action. 2017;10:1366136. doi: 10.1080/16549716.2017.1366136. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 21. Taffon P, Rossi G, Kindermans J-M, Van den Bergh R, Nguon C, Debackere M, et al. “I could not join because I had to work for pay”: a qualitative evaluation of falciparum malaria pro-active case detection in three rural Cambodian villages. PLoS One. 2018;13:0195809. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0195809. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 22. Fatima K, Qadri I. Battle against poliovirus in Pakistan. J Infect Dev Ctries. 2013;7:897–899. doi: 10.3855/jidc.3647. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 23. Yasuoka J, Poudel KC, Poudel-Tandukar K, Nguon C, Ly P, Socheat D, et al. Assessing the quality of service of village malaria workers to strengthen community-based malaria control in Cambodia. Malar J. 2010;9:109. doi: 10.1186/1475-2875-9-109. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 24. Rifkin SB, Muller F, Bichmann W. Primary health care: on measuring participation. Soc Sci Med. 1982;1988(26):931–940. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(88)90413-3. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 25. Draper AK, Hewitt G, Rifkin S. Chasing the dragon: developing indicators for the assessment of community participation in health programmes. Soc Sci Med. 1982;2010(71):1102–1109. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2010.05.016. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 26. Principles of Community Engagement (Second Edition). Atlanta: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2011. https://www.atsdr.cdc.gov/communityengagement/pdf/PCE_Report_508_FINAL.pdf . Accessed 11 Dec 2018.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data availability statement.

- View on publisher site

- PDF (892.2 KB)

- Collections

Similar articles

Cited by other articles, links to ncbi databases.

- Download .nbib .nbib

- Format: AMA APA MLA NLM

Add to Collections

- Open access

- Published: 28 February 2024

Malaria elimination and the need for intensive inter-country cooperation: a critical evaluation of regional technical co-operation in Southern Africa

- Chadwick H. Sikaala 1 ,

- Bongani Dlamini 1 ,

- Alphart Lungu 1 ,

- Phelele Fakudze 1 ,

- Mukosha Chisenga 1 ,

- Chishala Lukwesa Siame 1 ,

- Nyasha Mwendera 1 ,

- Dumisani Shaba 1 ,

- John M. Chimumbwa 1 &

- Immo Kleinschmidt 1 , 2 , 3

Malaria Journal volume 23 , Article number: 62 ( 2024 ) Cite this article

2407 Accesses

1 Citations

3 Altmetric

Metrics details

A Correction to this article was published on 08 April 2024

This article has been updated

Malaria elimination requires closely co-ordinated action between neighbouring countries. In Southern Africa several countries have reduced malaria to low levels, but the goal of elimination has eluded them thus far. The Southern Africa Development Community (SADC) Malaria Elimination Eight (E8) initiative was established in 2009 between Angola, Botswana, Eswatini, Mozambique, Namibia, South Africa, Zambia, and Zimbabwe to coordinate malaria interventions aiming to eliminate malaria by 2030. Cross-border coordination is important in malaria elimination settings as it strengthens surveillance, joint planning and implementation, knowledge exchange and optimal use of resources. This paper describes how this collaboration is realized in practice, its achievements and challenges, and its significance for malaria elimination prospects.

The ministers of health of the E8 countries oversee an intergovernmental technical committee supported by specialist working groups consisting of technical personnel from member countries and partner institutions. These technical working groups are responsible for malaria elimination initiatives in key focus areas such as surveillance, vector control, diagnosis, case management, behaviour change and applied research. The technical working groups have initiated and guided several collaborative projects which lay essential groundwork for malaria elimination.

The E8 collaboration has yielded achievements in the following key areas. (1) Establishment and evaluation of malaria border health posts to improve malaria services in border areas and reduce malaria among resident and, mobile and migrant populations. (2) The development of a regional malaria microscopy slide bank providing materials for diagnostic training and proficiency testing. (3) A facility for regional external competency assessment and training of malaria microscopy trainers in collaboration with the World Health Organization. (4) Entomology fellowships that improved capacity in entomological surveillance; an indoor residual spraying (IRS) training of trainers’ scheme to enhance the quality of this core intervention in the region. (5) Capacity development for regional malaria parasite genomic surveillance. (6) A mechanism for early detection of malaria outbreak through near real time reporting and a quarterly bulletins of malaria incidence in border districts.

Conclusions

The E8 technical working groups system embodies inter-country collaboration of malaria control and elimination activities. It facilitates sustained interaction between countries through a regional approach. The groundwork for elimination has been laid, but the challenge will be to maintain funding for collaboration at this level whilst reducing reliance on international donors and to build capacities necessary to prepare for malaria elimination.

The sixteen members of the Southern Africa Development Community (SADC) include countries with the highest malaria burden in the world. Whilst all SADC countries have the goal of eventually eliminating malaria, currently only Lesotho, Mauritius and Seychelles are malaria-free [ 1 ].

In 2009 SADC Ministers of Health (MOH) dedicated member countries to the goal of malaria elimination by establishing a multi-country regional initiative, consisting of the eight southernmost malaria endemic countries in the region—Angola, Botswana, Eswatini, Mozambique, Namibia, South Africa, Zambia, and Zimbabwe—called the Elimination 8 Initiative (E8). The E8 was established on the premise that no one country can eliminate malaria without coordinated efforts with its neighbours because of transboundary malaria between countries. Cross-border coordination is important in malaria elimination settings as it strengthens surveillance, joint planning and implementation, knowledge exchange and optimal use of resources [ 2 ]. The vision of the E8 was to eliminate malaria in four low-transmission ‘frontline countries’—Botswana, Eswatini, Namibia, and South Africa—by 2020, and to pave the way for elimination in four moderate to high-transmission ‘second line countries’- Angola, Mozambique, Zambia, and Zimbabwe—by 2030 [ 3 ]. The formation of the E8 initiative was in line with the 2008 World Health Organization (WHO) recommendation on elimination which stresses the need for strong collaboration and political will amongst countries forming regional elimination blocks which could support countries nearing elimination. A key focus of elimination strategies would be cross border transmission [ 4 ].

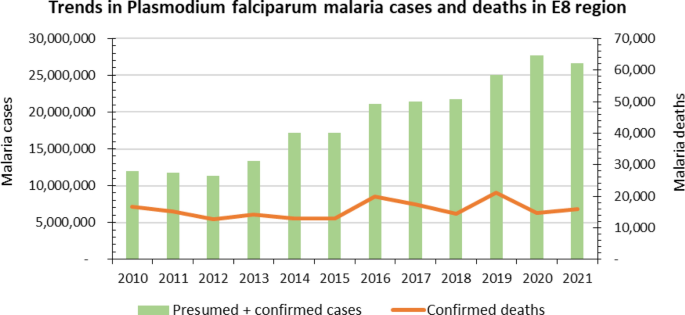

Three of the eight countries (Angola, Mozambique, and Zambia) contributed about 98% of Plasmodium falciparum malaria cases and 96% of malaria deaths during the decade from 2010 to 2021, underscoring the large heterogeneity of the malaria burden in the region [ 5 ]. From 2016, the region overall, experienced a gradual increase in malaria cases (Fig. 1 ), thus moving further away from the goal of zero malaria, although trends varied considerably between countries (Fig. 1 ).

Malaria Trends across the E8 Region 2010–2021. Source. Statistics adapted from the WHO World Malaria Report 2022 statistical tables

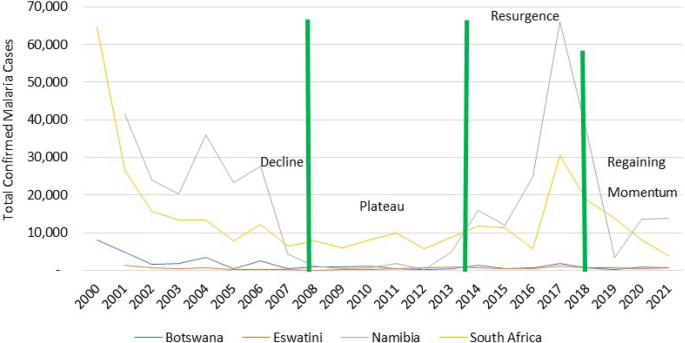

Frontline countries experienced sharp declines in malaria cases from 2000 to 2008, with case numbers remaining low up to 2014 (Fig. 2 ). Beginning in 2015, the region experienced a series of malaria outbreaks which have resulted in malaria resurgence, even where the possibilities of achieving elimination seemed to be in sight, particularly in Botswana, Eswatini and South Africa (Fig. 2 ). The malaria case resurgences can be attributed to, among other things, suboptimal coverages and quality of vector control, particularly indoor residual spraying and slow response where reactive case detection is practiced. In some areas, heavy rains caused population displacements and potentially increased malaria vector densities and receptivity, exposing vulnerabilities in epidemic response systems.

Progress towards malaria elimination in the frontline countries. Source. Statistics adapted from the World Malaria Report 2021 and E8 Scorecard 2013–2021

To regain momentum towards elimination, E8 facilitated the coordination of intensified efforts to identify and address systemic and persistent challenges, including cross-border planning to optimize deployment of interventions. This resulted in malaria cases in frontline countries declining from 99,658 in 2017 to 18,990 cases in 2021, putting malaria elimination back on track in these countries [ 6 ].

Despite this progress in frontline countries, the aim of elimination is continuously thwarted by imported cases from neighbouring second line countries. The region faces increased challenges of cross-border movement and interconnectedness which is common in many parts of sub-Sahara Africa [ 7 ]. The direction of migration is mainly from high burden second line countries to low burden first line countries primarily for economic reasons such as, seeking work and trade, and in some instances for medical treatment. A large proportion of short-term cross-border travel is circular, driven by family and community ties across [ 8 ]. This challenge is compounded by the lack of dedicated resources for malaria elimination in low transmission border districts of second line countries due in part to prioritization of funds towards higher burden districts in the north of these countries.

In response to malaria outbreaks and escalating cases, E8 Member States in 2018 re-committed themselves to strengthening inter-country cross-border collaboration by adopting the Windhoek Declaration to Elimination of Malaria [ 9 ].

This paper describes the way regional technical collaboration in malaria control and elimination has been implemented in southern Africa in practice, what it has achieved thus far and what challenges it is likely to face in future.

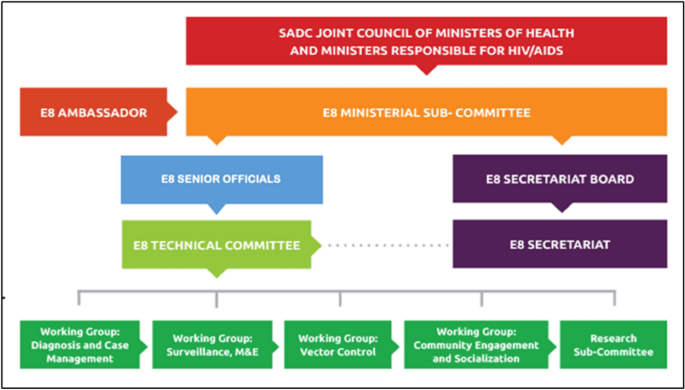

E8 governance structure and technical working groups

The E8 is governed by the ministers of health of the E8 member countries, acting as a subcommittee of the SADC Ministerial Council of Ministers of Health, supported by the E8 Technical Committee which consists of senior officials of health of member countries, and specialized technical working groups [ 10 ]. The E8 ministerial committee provides strategic oversight and leads diplomatic dialogue at ministerial level on behalf of the Member States. The E8 is supported by a Secretariat, which co-ordinates technical collaboration amongst E8 countries (Fig. 3 ) and convenes the working groups which review, plan and coordinate malaria elimination strategies across the region The secretariat is responsible for translating regional resolutions into action.

Governance structure of the Elimination Eight Initiative. Source. SADC-E8 website

The technical committee consists of the managers of all E8 national malaria control/elimination programmes; it facilitates the implementation of regional malaria control and elimination initiatives, and it oversees the specialist technical working groups.

E8 technical working groups

These are. (i) diagnosis and case management; (ii) surveillance, monitoring, and evaluation (SME); (iii) vector control and entomological surveillance (VC); (iv) community engagement and social behaviour, change and communication; and (v) a research sub-committee.

Each technical working groups consists of representatives from each of the member states with subject expertise relevant to the thematic area. Representatives of partner organizations (e.g., WHO) also attend these meetings. The technical working groups support implementation of regional malaria elimination activities through a coordinated multi-country malaria elimination approach. They convene biannually to consider new developments in their subject areas, and advance decisions and action points, subject to endorsement by the technical committee. The secretariat coordinates approved actionable activities and coordinates meetings. Actions requiring high-level engagement and advocacy are escalated to the Senior Officials and the E8 Ministerial Committee. The technical working groups provide strategic and technical guidance and inter-country harmonization of activities within their respective thematic areas in line with WHO formative guidance and agreed regional best practices.

The SME technical working group facilitates the coordination of malaria surveillance, data sharing and emergency response to malaria outbreaks and the dissemination of standard indicators of regional significance as reported by individual member countries. The VC technical working group develops and disseminates guidance of best practices in vector control and entomological surveillance and provides a platform to identify specific regional needs in vector control and entomology. The diagnosis and case management thematic area focuses on matters related to case management guidelines, therapeutic drug resistance monitoring and capacity development in diagnostics. The community engagement and social behaviour, change and communication technical working group facilitated the regional harmonization of community engagement interventions focussing on marginalized populations along borders. The research sub-committee identifies key regional research priorities in malaria elimination, promotes operational research and scrutinizes evidence on which policies in support of elimination are based. These roles are defined in each of the technical working group terms of reference. The priority projects initiated by the E8 technical working groups since their inception in 2016 are highlighted below.

Border health posts and malaria services in border areas

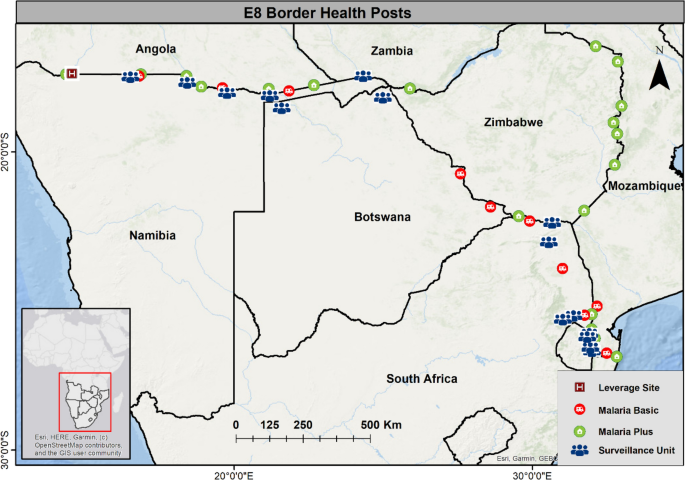

Due to the high interconnectedness of populations in the region, transit routes of MMPs are likely to lead to cross-border importation of parasites from high to low endemic countries thereby thwarting elimination efforts in the latter. To reduce cross-border malaria and to improve the provision of malaria services in border areas, 46 sites were identified along borders in 2017 between high and low transmission countries where border health posts were considered by national malaria programmes to have optimal impact [ 8 , 11 ]. Three types of health post were deployed (Table 1 ), located along five key international borders shown in Fig. 4 . All border posts were able to diagnose and treat malaria. Malaria plus units were accommodated in refurbished storage containers and able to additionally provide basic primary health care. Malaria basic units were mobile and provided malaria testing and treatment from a tent, whilst the Surveillance units provided malaria services from a vehicle. All units were staffed by a qualified nurse who was generally assisted by a Community Health Worker or an Environmental Health Officer. A small number of existing health facilities, called leverage border posts, were incorporated into this scheme.

Location of Border Health Posts along the five borders in the E8 region

The purpose of these malaria border health posts (BHP) was to improve access to malaria prevention, diagnosis, and treatment among underserved border communities and mobile migrant populations (MMP).

Between 2017 and 2020 approximately 1.26 million people were tested for malaria at these BHPs of which, about 76,000 (6%) tested positive and were given first line anti-malarial treatment in accordance with local treatment guidelines [ 12 ]. In 2020, these BHPs were transferred from the E8 secretariat to the health system of the country in which they were located. Whilst the BHPs have made malaria services more accessible to MMPs and residents in border areas, it has proved challenging for countries to fully fund these facilities from existing health budgets.

Following the establishment of the BHPs, the E8 commissioned a study to gain insight into malaria service delivery in border areas, and to assess knowledge, attitudes and practices related to malaria and the functionality and role of the health posts. The assessment was carried out through cross sectional surveys among residents and MMPs in selected sites in border areas in Angola, Botswana, Mozambique, Namibia, South Africa, Zambia, and Zimbabwe [ 8 ].

This assessment found that there was a high-level of knowledge of the causes, symptoms, and prevention of malaria amongst most respondents, that nearly all those who reported a positive blood test result when seeking care received medication, and that most but not all border residents had access to primary prevention against malaria in the form of insecticide treated nets or indoor residual spraying. Most respondents said that when they presented at health facilities with fever, they were tested for malaria. However, in areas of low endemicity respondents were not always offered a blood test for malaria when presenting with malaria symptoms (fever). Travel across borders was frequent and often associated with sleeping outside without protection against infective mosquito bites. The results were reported in detail to each of the NMCPs in participating countries, and remedial action was undertaken where appropriate [ 8 ]. This work was overseen by the research subcommittee and the SME technical working group.

Capacity building and research

Malaria microscopy slide bank and external microscopy competency assessment.

Since the WHO requires malaria microscopy as a confirmatory diagnostic method during the process of malaria elimination certification [ 13 ], it is essential that regional capacity for accurate microscopy is created in the E8 region. Through the diagnosis and case management working group a Malaria Slide Bank (MSB) was established as a regional facility in 2018. The MSB was set up at the National Institute for Communicable Diseases (NICD), South Africa, where it is currently accommodated, maintained, and administered. The MSB constitutes a collection of reference slides of known malaria parasite densities and species. The slides are used for microscopy trainings, competency assessments and certifications of laboratory personnel in the region. With the assistance of the WHO, the MSB is used for managing a regional Proficiency Testing Scheme for malaria microscopy for national reference laboratories in E8 countries for quality assurance in malaria diagnosis [ 14 ]. The facility includes an online interface for registration, result submission, and provision of supportive interaction with participants. The MSB serves as a regional reference facility, strengthening laboratory diagnosis and parasitological testing capability, thereby contributing to the phasing out of any remaining presumptive treatment of malaria based on clinical symptoms alone [ 14 ].

Training and certification of laboratory personnel is carried out under the WHO external competency assessment for malaria microscopists (ECAMM) accreditation programme using the MSB. To date more than 100 personnel from laboratories across the E8 region have been trained and certified under this scheme.

Malaria genomics in E8

In 2018 the E8 Research Subcommittee identified several research and surveillance areas that should be prioritized to advance malaria elimination in the region. These included routine surveillance of parasite molecular mutations associated with anti-malarial drug resistance, the early detection of histidine rich protein (HRP2/3) gene deletions which can render some types of malaria rapid diagnostic tests (RDT) insensitive, and the provision of overall information on parasite connectivity and sources/sinks across the region. To address these gaps in information, the E8 in collaboration with the University of California San Francisco (UCSF), the NICD in South Africa and Africa Centres for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) launched the Genomics for Malaria Elimination in E8 countries (GenE8) project in 2021. The project aimed to strengthen malaria parasite surveillance by building capacity in the generation, analysis, and use of parasite genomic data for programmatic decision-making and was instrumental in standardizing assays for genomic work across the region.

Under this project a regional cross-sectional study was conducted collecting blood samples for genomic analysis at selected health facilities of E8 countries in the 2022–2023 transmission season. The data from this survey represented a baseline against which future genomic data can be compared. The project intends to identify use cases of genomic data to support programmatic decision-making, including the monitoring of molecular markers of resistance to anti-malarial drugs and mutations that could affect the functioning of RDTs. To build capacity in the use of parasite genomics in malaria surveillance, a small cohort of suitable laboratory personnel from E8 countries were recruited into a fellowship programme. A series of workshops were conducted to train candidates in malaria parasite genomics including skills in analysing and interpreting malaria parasite genomic data. Participants were also responsible for the standardization of assays and laboratory methods to facilitate a coordinated scale-up of malaria molecular surveillance (MMS) across the region. The research sub-committee and the case management and diagnosis technical working groups collaborated to support these projects.

Strengthening vector control and entomology capacity

Vector control through indoor residual spraying (IRS) and distribution of long-lasting insecticidal nets (LLIN) has been the cornerstone for controlling malaria in E8 countries. The effective implementation of IRS requires rigorous planning, skilled human resource and co-ordinated deployment to achieve the WHO optimal coverage and quality of application for maximum impact.

To ensure that IRS is consistently implemented to a high standard, and to avoid the suboptimal coverage and poor quality of IRS that previously contributed to the malaria resurgences during the 2015 malaria season, the vector control technical working group, in collaboration with WHO, developed a standardized training of trainer’s manual and slide deck in 2019. This served as a guide for harmonizing training, implementation, monitoring, and quality assurance for IRS [ 15 ]. The use of this manual during in-country trainings has resulted in the adherence to a set of minimum standards linked to indicators that facilitate a like-for-like comparison of IRS coverage across the region. A total of 24 vector control experts (3 per country) were trained as regional trainers of trainers using this guide. This cohort of experts will increase capacity by conducting in-country cascade trainings.

To address the lack of entomological surveillance capacity in the region, the vector control and research sub-committee initiated a regional entomology fellowship in 2017 [ 16 ] . The fellowship involved a rigorous process to select suitable candidates from each of the E8 countries. The selected fellows underwent intensive training at the University of Witwatersrand (South Africa), Ifakara Health Institute (Tanzania) and Liverpool School of Tropical Medicine (UK). Fellows conducted a 6-month in-country study project to address an identified entomological operational research gap within the national malaria elimination strategies of their country. Each fellow was assigned a mentor from a research institute within their respective countries. An assessment was conducted to evaluate the effectiveness of the fellowship [ 17 ]. Based on the recommendations of this assessment a second entomology research fellowship has been initiated to address several entomological research priorities such as vector species identification; vector resting and feeding behaviours; entomological factors associated with residual transmission in elimination settings and monitoring the efficacy of IRS insecticides currently in use in E8 border districts. This work included entomological surveillance to detect the presence of invasive vectors, such as Anopheles stephensi. The second fellowship programme comprised of 8 fellows, each nominated by their respective NMCP.

Addressing health access and equity barriers to malaria services in E8

The E8 faces disparities in health access among disadvantaged rural and marginalized communities, migrants, and mobile populations [ 18 ]. Non-discriminatory services are needed to conform with human rights and gender responsive policies. To identify socio-economic, gender and cultural barriers affecting equity and access to health services among MMPs and in communities living along borders, E8 coordinated a regional assessment, known as the Matchbox Assessment through the community engagement and social behaviour, change and communication technical working group. Groups consisting of male and female MMPs from a homogenous occupational category in each district were selected to participate in focus group discussions using convenience sampling. Focus group discussions were also held with community health workers. Key informant interviews were held with representatives of local health facilities, and community leaders [ 19 ]. Based on the assessment the E8 is developing regional community engagement and social behaviour, change and communication elimination guidelines to expand access to health services among underserved populations.

Regional malaria surveillance