Learn about the nursing care management of patients with asthma in this nursing study guide .

Table of Contents

- What is Asthma?

Pathophysiology

- Statistics and Epidemiology

Clinical Manifestations

Complications, assessment and diagnostic findings, pharmacologic therapy, peak flow monitoring, nursing assessment, nursing diagnosis, nursing care planning & goals, nursing interventions, discharge and home care guidelines, documentation guidelines, what is asthma.

Asthma affects people in their different stages in life, yet it can be avoided and treated.

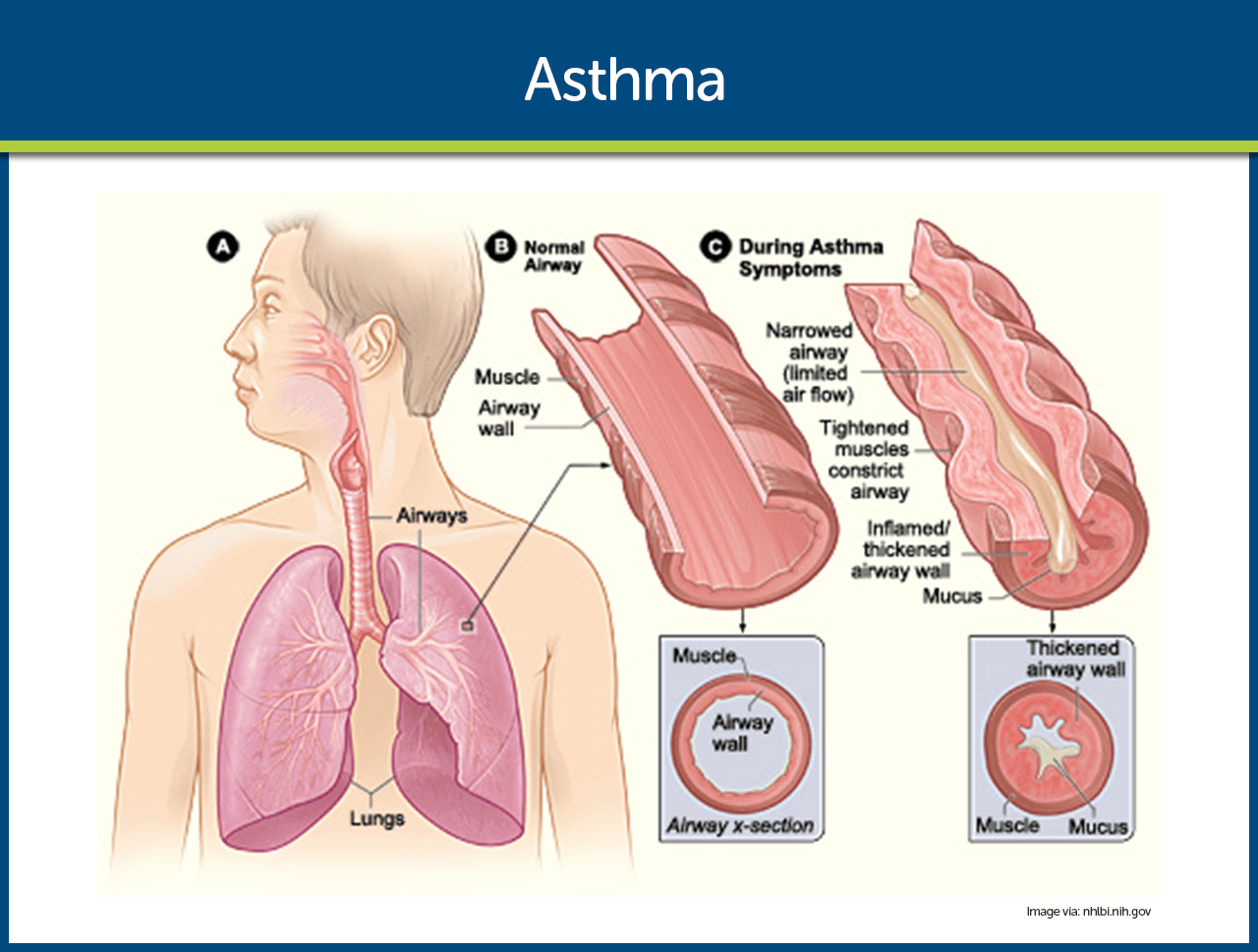

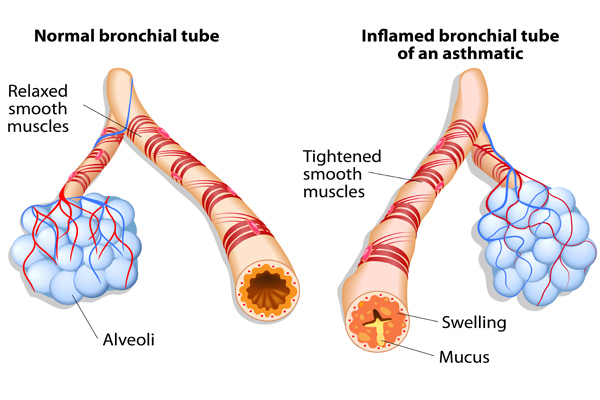

- Asthma is a chronic inflammatory disease of the airways that causes airway hyperresponsiveness, mucosal edema , and mucus production.

- Inflammation ultimately leads to recurrent episodes of asthma symptoms.

- Patients with asthma may experience symptom-free periods alternating with acute exacerbations that last from minutes to hours or days.

- Asthma, the most common chronic disease of childhood, can begin at any age.

The underlying pathophysiology in asthma is reversible and diffuse airway inflammation that leads to airway narrowing.

- Activation. When the mast cells are activated, it releases several chemicals called mediators.

- Perpetuation. These chemicals perpetuate the inflammatory response, causing increased blood flow, vasoconstriction,, fluid leak from the vasculature, the attraction of white blood cells to the area, and bronchoconstriction.

- Bronchoconstriction. Acute bronchoconstriction due to allergens results from a release of mediators from mast cells that directly contract the airway.

- Progression. As asthma becomes more persistent, the inflammation progresses and other factors may be involved in the airflow limitation.

Statistics and Epidemiology

Asthma is considered the most common chronic disease of childhood and is a disruptive disease that affects school and work attendance.

- Asthma affects more than 22 million people in the United States.

- Asthma accounts for more than 497, 000 hospitalizations annually.

- The total economic cost of asthma exceeds $27.6 billion.

Despite increased knowledge on the pathology of asthma and the development of improved medications and management plans, the death rate from the disease continues to rise. Here are some of the factors that influence the development of asthma.

- Allergy . Allergy is the strongest predisposing factor for asthma.

- Chronic exposure to airway irritants. Irritants can be seasonal (grass, tree, and weed pollens) or perennial (mold, dust, roaches, animal dander).

- Exercise. Too much exercise can also cause asthma.

- Stress/ Emotional upset. This can trigger constriction of the airway leading to asthma.

- Medications. Certain medications can trigger asthma.

The signs and symptoms of asthma can be easily identified, so once the following symptoms are observed, a visit to the physician is necessary.

- Most common symptoms of asthma are cough (with or without mucus production), dyspnea , and wheezing (first on expiration , then possibly during inspiration as well).

- Cough . There are instances that cough is the only symptom.

- Dyspnea. General tightness may occur which leads to dyspnea .

- Wheezing. There may be wheezing, first on expiration, and then possibly during inspiration as well.

- Asthma attacks frequently occur at night or in the early morning.

- An asthma exacerbation is frequently preceded by increasing symptoms over days, but it may begin abruptly.

- Expiration requires effort and becomes prolonged.

- As exacerbation progresses, central cyanosis secondary to severe hypoxia may occur.

- Additional symptoms, such as diaphoresis, tachycardia, and a widened pulse pressure, may occur.

- Exercise-induced asthma: maximal symptoms during exercise, absence of nocturnal symptoms, and sometimes only a description of a “choking” sensation during exercise.

- A severe, continuous reaction, status asthmaticus, may occur. It is life-threatening.

- Eczema, rashes, and temporary edema are allergic reactions that may be noted with asthma.

Patients with recurrent asthma should undergo tests to identify the substances that precipitate the symptoms.

- Allergens . Allergens, either seasonal or perennial, can be prevented through avoiding contact with them whenever possible.

- Knowledge. Knowledge is the key to quality asthma care.

- Evaluation. Evaluation of impairment and risk are key in the control.

Complications for asthma include the following:

- Status asthmaticus . Airway obstruction in status asthmaticus often results in hypoxemia .

- Respiratory failure . Asthma, if left untreated, progresses to respiratory failure.

- Pneumonia . Mucus that pools in the lungs and becomes infected can lead to the development of pneumonia .

To determine the diagnosis of asthma, the clinician must determine that episodic symptoms of airway obstruction are present.

- Positive family history . Asthma is a hereditary disease, and can be possibly acquired by any member of the family who has asthma within their clan.

- Environmental factors . Seasonal changes, high pollen counts, mold, pet dander, climate changes, and air pollution are primarily associated with asthma.

- Comorbid conditions . Comorbid conditions that may accompany asthma may include gastroeasophageal reflux, drug-induced asthma, and allergic broncopulmonary aspergillosis.

Medical Management

Immediate intervention may be necessary, because continuing and progressive dyspnea leads to increased anxiety , aggravating the situation.

- Short-acting beta 2 – adrenergic agonists . These are the medications of choice for relief of acute symptoms and prevention of exercise-induced asthma.

- Anticholinergics . Anticholinergics inhibit muscarinic cholinergic receptors and reduce intrinsic vagal tone of the airway.

- Corticosteroids. Corticosteroids are most effective in alleviating symptoms, improving airway function, and decreasing peak flow variability.

- Leukotriene modifiers. Anti Leukotrienes are potent bronchoconstrictors that also dilate blood vessels and alter permeability.

- Immunomodulators . Prevent binding of IgE to the high affinity receptors of basophils and mast cells.

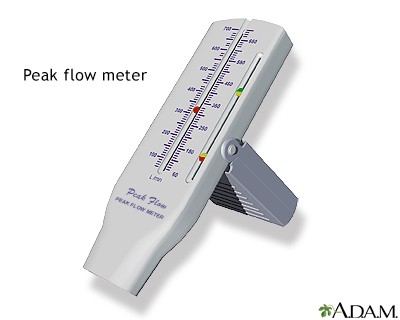

- Peak flow meters. Peak flow meters measure the highest airflow during a forced expiration.

- Daily peak flow monitoring. This is recommended for patients who meet one or more of the following criteria: have moderate or severe persistent asthma, have poor perception of changes in airflow or worsening symptoms, have unexplained response to environmental or occupational exposures, or at the discretion of the clinician or patient.

- Function. If peak flow monitoring is used, it helps measure asthma severity and, when added to symptom monitoring, indicates the current degree of asthma control.

Nursing Management

The immediate care of patients with asthma depends on the severity of the symptoms.

Assessment of a patient with asthma includes the following:

- Assess the patient’s respiratory status by monitoring the severity of the symptoms.

- Assess for breath sounds.

- Assess the patient’s peak flow.

- Assess the level of oxygen saturation through the pulse oximeter.

- Monitor the patient’s vital signs.

Based on the data gathered, the nursing diagnoses appropriate for the patient with asthma include:

- Ineffective airway clearance related to increased production of mucus and bronchospasm.

- Impaired gas exchange related to altered delivery of inspired O2.

- Anxiety related to perceived threat of death.

Main Article: 5 Bronchial Asthma Nursing Care Plans

To achieve success in the treatment of a patient with asthma, the following goals should be applied:

- Maintenance of airway patency .

- Expectoration of secretions.

- Demonstration of absence/reduction of congestion with breath sounds clear, respirations noiseless, improved oxygen exchange.

- Verbalization of understanding of causes and therapeutic management regimen.

- Demonstration of behaviors to improve or maintain clear airway.

- Identification of potential complications and how to initiate appropriate preventive or corrective actions.

The nurse generally performs the following interventions:

- Assess history. Obtain a history of allergic reactions to medications before administering medications.

- Assess respiratory status . Assess the patient’s respiratory status by monitoring the severity of symptoms, breath sounds, peak flow, pulse oximetry, and vital signs.

- Assess medications. Identify medications that the patient is currently taking. Administer medications as prescribed and monitor the patient’s responses to those medications; medications may include an antibiotic if the patient has an underlying respiratory infection .

- Pharmacologic therapy. Administer medications as prescribed and monitor patient’s responses to medications.

- Fluid therapy . Administer fluids if the patient is dehydrated.

To determine the effectiveness of the plan of care, evaluation must be performed. The following must be evaluated:

- Maintenance of airway patency.

- Expectoration or clearance of secretions.

- Absence /reduction of congestion with breath sound clear, noiseless respirations, and improved oxygen exchange.

- Verbalized understanding of causes and therapeutic management regimen.

- Demonstrated behaviors to improve or maintain clear airway.

- Identified potential complications and how to initiate appropriate preventive or corrective actions.

A major challenge is to implement basic asthma management principles at the home and community level.

- Collaboration. The complex therapy of treating asthma at home needs collaboration between the patient and the health care provider to determine the desired outcomes and to formulate a plan to achieve those outcomes.

- Health education. Patient teaching is a critical component of care for patients with asthma. Teach patient and family about asthma (chronic inflammatory), purpose and action of medications, triggers to avoid and how to do so, and proper inhalation technique. Instruct patient and family about peak-flow monitoring. Obtain current educational materials for the patient based on the patient’s diagnosis, causative factors, educational level, and cultural background.

- Compliance to therapy. Nurses should emphasize adherence to the prescribed therapy, preventive measures, and the need to keep follow-up appointments with health care providers. Teach patient how to implement an action plan and how and when to seek assistance.

- Home visits. Home visits by the nurse to assess the home environment for allergens may be indicated for patients with recurrent exacerbations.

Documentation is a necessary part of the nursing care provided, and the following data must be documented:

- Related factors for individual client.

- Breath sounds, presence and character of secretions, and use of accessory muscles for breathing.

- Character of cough and sputum.

- Respiratory rate, pulse oximetry/o2 saturation, and vital signs.

- Plan of care and who is involved in planning .

- Teaching plan.

- Client’s response to interventions, teaching, and actions performed.

- Use of respiratory devices/airway adjuncts.

- Response to medications administered.

- Attainment or progress towards desired outcomes.

- Modifications to the plan of care.

Posts related to Asthma:

- Asthma and COPD NCLEX Practice Quiz 1 (50 Items)

- Asthma and COPD NCLEX Practice Quiz 2 (50 Items)

- 5 Bronchial Asthma Nursing Care Plans

5 thoughts on “Asthma”

Perfect for students

I would like to use some of this key information in a student case study that I’m writing but am hesitant to do so because I don’t see enough information here about how to cite the reference. I suggest you add a widget/button that provides an APA style reference citation. It would also bring alot of free advertisement. : )

Thanks I really got what I wanted

You are really great, will like to meet you one day in America

Great lecture

Leave a Comment Cancel reply

Case Study: Managing Severe Asthma in an Adult

—he follows his treatment plan, but this 40-year-old male athlete has asthma that is not well-controlled. what’s the next step.

By Kirstin Bass, MD, PhD Reviewed by Michael E. Wechsler, MD, MMSc

This case presents a patient with poorly controlled asthma that remains refractory to treatment despite use of standard-of-care therapeutic options. For patients such as this, one needs to embark on an extensive work-up to confirm the diagnosis, assess for comorbidities, and finally, to consider different therapeutic options.

Case presentation and patient history

Mr. T is a 40-year-old recreational athlete with a medical history significant for asthma, for which he has been using an albuterol rescue inhaler approximately 3 times per week for the past year. During this time, he has also been waking up with asthma symptoms approximately twice a month, and has had three unscheduled asthma visits for mild flares. Based on the National Asthma Education and Prevention Program guidelines , Mr. T has asthma that is not well controlled. 1

As a result of these symptoms, spirometry was performed revealing a forced expiratory volume in the first second (FEV1) of 78% predicted. Mr. T then was prescribed treatment with a low-dose corticosteroid, fluticasone 44 mcg at two puffs twice per day. However, he remained symptomatic and continued to use his rescue inhaler 3 times per week. Therefore, he was switched to a combination inhaled steroid and long-acting beta-agonist (LABA) (fluticasone propionate 250 mcg and salmeterol 50 mcg, one puff twice a day) by his primary care doctor.

Initial pulmonary assessment Even with this step up in his medication, Mr. T continued to be symptomatic and require rescue inhaler use. Therefore, he was referred to a pulmonologist, who performed the initial work-up shown here:

- Spirometry, pre-albuterol: FEV1 79%, post-albuterol: 12% improvement

- Methacholine challenge: PC 20 : 1.0 mg/mL

- Chest X-ray: Within normal limits

Continued pulmonary assessment His dose of inhaled corticosteroid (ICS) and LABA was increased to fluticasone 500 mcg/salmeterol 50 mcg, one puff twice daily. However, he continued to have symptoms and returned to the pulmonologist for further work-up, shown here:

- Chest computed tomography (CT): Normal lung parenchyma with no scarring or bronchiectasis

- Sinus CT: Mild mucosal thickening

- Complete blood count (CBC): Within normal limits, white blood cells (WBC) 10.0 K/mcL, 3% eosinophils

- Immunoglobulin E (IgE): 25 IU/mL

- Allergy-skin test: Positive for dust, trees

- Exhaled NO: Fractional exhaled nitric oxide (FeNO) 53 parts per billion (pbb)

Assessment for comorbidities contributing to asthma symptoms After this work-up, tiotropium was added to his medication regimen. However, he remained symptomatic and had two more flares over the next 3 months. He was assessed for comorbid conditions that might be affecting his symptoms, and results showed:

- Esophagram/barium swallow: Negative

- Esophageal manometry: Negative

- Esophageal impedance: Within normal limits

- ECG: Within normal limits

- Genetic testing: Negative for cystic fibrosis, alpha1 anti-trypsin deficiency

The ear, nose, and throat specialist to whom he was referred recommended only nasal inhaled steroids for his mild sinus disease and noted that he had a normal vocal cord evaluation.

Following this extensive work-up that transpired over the course of a year, Mr. T continued to have symptoms. He returned to the pulmonologist to discuss further treatment options for his refractory asthma.

Diagnosis Mr. T has refractory asthma. Work-up for this condition should include consideration of other causes for the symptoms, including allergies, gastroesophageal reflux disease, cardiac disease, sinus disease, vocal cord dysfunction, or genetic diseases, such as cystic fibrosis or alpha1 antitrypsin deficiency, as was performed for Mr. T by his pulmonary team.

Treatment options When a patient has refractory asthma, treatment options to consider include anticholinergics (tiotropium, aclidinium), leukotriene modifiers (montelukast, zafirlukast), theophylline, anti-immunoglobulin E (IgE) antibody therapy with omalizumab, antibiotics, bronchial thermoplasty, or enrollment in a clinical trial evaluating the use of agents that modulate the cell signaling and immunologic responses seen in asthma.

Treatment outcome Mr. T underwent bronchial thermoplasty for his asthma. One year after the procedure, he reports feeling great. He has not taken systemic steroids for the past year, and his asthma remains controlled on a moderate dose of ICS and a LABA. He has also been able to resume exercising on a regular basis.

Approximately 10% to 15% of asthma patients have severe asthma refractory to the commonly available medications. 2 One key aspect of care for this patient population is a careful workup to exclude other comorbidities that could be contributing to their symptoms. Following this, there are several treatment options to consider, as in recent years there have been several advances in the development of asthma therapeutics. 2

Treatment options for refractory asthma There are a number of currently approved therapies for severe, refractory asthma. In addition to therapy with ICS or combination therapies with ICS and LABAs, leukotriene antagonists have good efficacy in asthma, especially in patients with prominent allergic or exercise symptoms. 2 The anticholinergics, such as tiotropium, which was approved for asthma in 2015, enhance bronchodilation and are useful adjuncts to ICS. 3-5 Omalizumab is a monoclonal antibody against IgE recommended for use in severe treatment-refractory allergic asthma in patients with atopy. 2 A nonmedication therapeutic option to consider is bronchial thermoplasty, a bronchoscopic procedure that uses thermal energy to disrupt bronchial smooth muscle. 6,7

Personalizing treatment for each patient It is important to personalize treatment based on individual characteristics or phenotypes that predict the patient's likely response to treatment, as well as the patient's preferences and practical issues, such as adherence and cost. 8

In this case, tiotropium had already been added to Mr. T's medications and his symptoms continued. Although addition of a leukotriene modifier was an option for him, he did not wish to add another medication to his care regimen. Omalizumab was not added partly for this reason, and also because of his low IgE level. As his bronchoscopy was negative, it was determined that a course of antibiotics would not be an effective treatment option for this patient. While vitamin D insufficiency has been associated with adverse outcomes in asthma, T's vitamin D level was tested and found to be sufficient.

We discussed the possibility of Mr. T's enrollment in a clinical trial. However, because this did not guarantee placement within a treatment arm and thus there was the possibility of receiving placebo, he opted to undergo bronchial thermoplasty.

Bronchial thermoplasty Bronchial thermoplasty is effective for many patients with severe persistent asthma, such as Mr. T. This procedure may provide additional benefits to, but does not replace, standard asthma medications. During the procedure, thermal energy is delivered to the airways via a bronchoscope to reduce excess airway smooth muscle and limit its ability to constrict the airways. It is an outpatient procedure performed over three sessions by a trained physician. 9

The effects of bronchial thermoplasty have been studied in several trials. The first large-scale multicenter randomized controlled study was the Asthma Intervention Research (AIR) Trial , which enrolled patients with moderate to severe asthma. 10 In this trial, patients who underwent the procedure had a significant improvement in asthma symptoms as measured by symptom-free days and scores on asthma control and quality of life questionnaires, as well as reductions in mild exacerbations and increases in morning peak expiratory flow. 10 Shortly after the AIR trial, the Research in Severe Asthma (RISA) trial was conducted to evaluate bronchial thermoplasty in patients with more severe, symptomatic asthma. 11 In this population, bronchial thermoplasty resulted in a transient worsening of asthma symptoms, with a higher rate of hospitalizations during the treatment period. 11 Hospitalization rate equalized between the treatment and control groups in the posttreatment period, however, and the treatment group showed significant improvements in rescue medication use, prebronchodilator forced expiratory volume in the first second (FEV1) % predicted, and asthma control questionnaire scores. 11

The AIR-2 trial followed, which was a multicenter, randomized, double-blind, sham-controlled study of 288 patients with severe asthma. 6 Similar to the RISA trial, patients in the treatment arm of this trial experienced an increase in adverse respiratory effects during the treatment period, the most common being airway irritation (including wheezing, chest discomfort, cough, and chest pain) and upper respiratory tract infections. 6

The majority of adverse effects occurred within 1 day of the procedure and resolved within 7 days. 6 In this study, bronchial thermoplasty was found to significantly improve quality of life, as well as reduce the rate of severe exacerbations by 32%. 6 Patients who underwent the procedure also reported fewer adverse respiratory effects, fewer days lost from work, school, or other activities due to asthma, and an 84% risk reduction in emergency department visits. 6

Long-term (5-year) follow-up studies have been conducted for patients in both the AIR and the AIR-2 trials. In patients who underwent bronchial thermoplasty in either study, the rate of adverse respiratory effects remained stable in years 2 to 5 following the procedure, with no increase in hospitalizations or emergency department visits. 7,12 Additionally, FEV1 remained stable throughout the 5-year follow-up period. 7,12 This finding was maintained in patients enrolled in the AIR-2 trial despite decreased use of daily ICS. 7

Bronchial thermoplasty is an important addition to the asthma treatment armamentarium. 7 This treatment is currently approved for individuals with severe persistent asthma who remain uncontrolled despite the use of an ICS and LABA. Several clinical trials with long-term follow-up have now demonstrated its safety and ability to improve quality of life in patients with severe asthma, such as Mr. T.

Severe asthma can be a challenge to manage. Patients with this condition require an extensive workup, but there are several treatments currently available to help manage these patients, and new treatments are continuing to emerge. Managing severe asthma thus requires knowledge of the options available as well as consideration of a patient's personal situation-both in terms of disease phenotype and individual preference. In this case, the patient expressed a strong desire to not add any additional medications to his asthma regimen, which explained the rationale for choosing to treat with bronchial thermoplasty. Personalized treatment necessitates exploring which of the available or emerging options is best for each individual patient.

Published: April 16, 2018

- 1. National Asthma Education and Prevention Program: Asthma Care Quick Reference.

- 2. Olin JT, Wechsler ME. Asthma: pathogenesis and novel drugs for treatment. BMJ . 2014;349:g5517.

- 3. Boehringer Ingelheim. Asthma: U.S. FDA approves new indication for SPIRIVA Respimat [press release]. September 16, 2015.

- 4. Peters SP, Kunselman SJ, Icitovic N, et al. Tiotropium bromide step-up therapy for adults with uncontrolled asthma. N Engl J Med . 2010;363:1715-1726.

- 5. Kerstjens HA, Engel M, Dahl R. Tiotropium in asthma poorly controlled with standard combination therapy. N Engl J Med . 2012;367:1198-1207.

- 6. Castro M, Rubin AS, Laviolette M, et al. Effectiveness and safety of bronchial thermoplasty in the treatment of severe asthma: a multicenter, randomized, double-blind, sham-controlled clinical trial. Am J Respir Crit Care Med . 2010;181:116-124.

- 7. Wechsler ME, Laviolette M, Rubin AS, et al. Bronchial thermoplasty: long-term safety and effectiveness in patients with severe persistent asthma. J Allergy Clin Immunol . 2013;132:1295-1302.

- 8. Global Initiative for Asthma: Pocket Guide for Asthma Management and Prevention (for Adults and Children Older than 5 Years).

- 10. Cox G, Thomson NC, Rubin AS, et al. Asthma control during the year after bronchial thermoplasty. N Engl J Med . 2007;356:1327-1337.

- 11. Pavord ID, Cox G, Thomson NC, et al. Safety and efficacy of bronchial thermoplasty in symptomatic, severe asthma. Am J Respir Crit Care Med . 2007;176:1185-1191.

- 12. Thomson NC, Rubin AS, Niven RM, et al. Long-term (5 year) safety of bronchial thermoplasty: Asthma Intervention Research (AIR) trial. BMC Pulm Med . 2011;11:8.

Treatable traits and future exacerbation risk in severe asthma, baker’s asthma, the long-term trajectory of mild asthma, age, gender, & systemic corticosteroid comorbidities, ask the expert: william busse, md, challenges the current definition of the atopic march, considering the curveballs in asthma treatment, do mucus plugs play a bigger role in chronic severe asthma than previously thought, an emerging subtype of copd is associated with early respiratory disease.

Nursing Case Study for Pediatric Asthma

Watch More! Unlock the full videos with a FREE trial

Included In This Lesson

Study tools.

Access More! View the full outline and transcript with a FREE trial

Anthony is a 6-yr-old male patient brought to the pediatric ER with a history of asthma since he came home from the NICU as an infant. He lives with his parents, Bob and Josh, who adopted him after fostering him from age 4 months. They have tried the usual nebulizer treatments but Anthony is not responding as usual, so they brought him for evaluation.

Initial assessment in triage reveals both inspiratory and expiratory wheezes, dyspnea, tachypnea, diaphoresis, and retractions.

BP 70/40 mmHg SpO2 93% on room air HR 131 bpm RR 32bpm at rest Temp 38.3°C

What physiologic issue is Anthony suffering from based on the assessment findings?

- Respiratory distress is evidenced by both vital signs and physical assessment findings. His RR and HR are high. He is also sweating and having retractions which may indicate he is working hard to try to establish oxygen exchange.

What signs and symptoms might occur that would show worsening of his condition?

- Skin color changes (i.e. blue or bluish around the mouth or even inside the mouth, blue nail beds, gray or pale compared to usual)

- Grunting on exhalation (this indicates the body is trying to keep air in the lungs)

- Stridor (this is heard in the upper airway and can be an ominous sign)

- Changes in the level of consciousness (becoming lethargic or drowsy)

Anthony is pale but not gray. His lips do indicate a very faint bluish tinge. He can speak but it appears difficult.

What medications might the nurse expect the provider to order?

- Short-acting beta-agonists (SABAs)

- Racemic albuterol – A racemic mixture of albuterol (salbutamol) is the primary SABA used for quick relief of acute asthma symptoms and exacerbations.

- Levalbuterol – Levalbuterol (Levosalbutamol), the R-enantiomer, is the active isomer of racemic albuterol that confers the bronchodilator effects. Levalbuterol is approved in the United States for the treatment of bronchospasm in children ≥4 years of age via hydrofluoroalkane (HFA) metered-dose inhaler (MDI) and ≥6 years of age via solution for nebulizer

What side effects might occur from the medications ordered?

- “The most common side effects are tremor, increased heart rate, and palpitations” Anthony may report feeling jittery due to the activation of beta receptors.

After administration of racemic albuterol, Anthony now has a RR of 22 and O2 saturation of 95% on room air. However, the provider decides to admit him to the inpatient pediatric observation unit. His parents ask if there are ways to keep him from continually being admitted to the hospital.

What are some education topics to bring up to Anthony’s parents?

- Controlling asthma triggers — The factors that set off or worsen asthma symptoms are called “triggers.” Identifying and avoiding asthma triggers is essential to keeping symptoms under control. Common asthma triggers generally fall into several categories:

- Allergens (including dust mites, pollen, mold, cockroaches, mice, cats, and dogs)

- Respiratory infections, such as the common cold or the flu

- Irritants (such as tobacco smoke, chemicals, and strong odors or fumes)

- Exercise or other physical activity

What does the nurse understand about this medication?

- Systemic corticosteroids are an essential treatment option for many disease states, especially asthma. These medications reduce the length and severity of asthma exacerbations and reduce the need for hospitalization or ED visits. It is important for asthma patients to receive prednisolone as soon as possible after the onset of symptoms that are bronchodilator-unresponsive to attain these benefits.

- Although usually prescribed for a 5- to 7-day period, oral corticosteroids are not without adverse effects. The most common adverse effects are the same for the majority of oral corticosteroids and include increased appetite, weight gain, flushed face.

- Increased risk of infections, especially with common bacterial, viral and fungal microorganisms. Thinning bones (osteoporosis) and fractures happen over time, be mindful this may cause problems in an energetic child. Suppressed adrenal gland hormone production may result in a variety of signs and symptoms, including severe fatigue, loss of appetite, nausea and muscle weakness.

Anthony sleeps during the night shift and the next day, his pediatrician makes rounds and discusses a change in the severity rating of Anthony’s asthma.

What does the nurse know about asthma severity and how it is determined?

- Asthma severity is the intrinsic intensity of the disease. Assessment of asthma severity is made on the basis of components of current impairment and future risk. The severity is determined by the most severe category measured

Bob and Josh are interested in meeting with respiratory therapy for assistance with inhalers. They say that Anthony has trouble using inhaler devices.

Inviting respiratory therapy to provide parent teaching is an example of what? How can this department help the family?

- Interdisciplinary team collaboration.

- Teaching about medications, proper inhaler (or other equipment) use, thorough explanation of peak expiratory flow (PEF) measuring, ways to help control RR.

After lunch, Anthony is ready to be discharged. His parents verbalize gratitude to the staff and thank the team for helping with education.

What can the nurse help Bob and Josh start to establish to try to help them with Anthony’s condition?

- Setting goals and planning. Preparing for an action plan (“Asthma ‘action plan’ is a form or document that your child’s provider can help you put together; it includes instructions about how to monitor symptoms and what to do when they happen. Asthma action plans are available for children up to five years old, for children five years and older and adults and for school. An action plan can tell you when to add or increase medications, when to call your child’s provider, and when to get immediate emergency help. This can help you know what to do in the event of an asthma attack. Different people can have different action plans, and your child’s action plan will likely change over time.”)

View the FULL Outline

When you start a FREE trial you gain access to the full outline as well as:

- SIMCLEX (NCLEX Simulator)

- 6,500+ Practice NCLEX Questions

- 2,000+ HD Videos

- 300+ Nursing Cheatsheets

“Would suggest to all nursing students . . . Guaranteed to ease the stress!”

References:

View the full transcript, nursing case studies.

This nursing case study course is designed to help nursing students build critical thinking. Each case study was written by experienced nurses with first hand knowledge of the “real-world” disease process. To help you increase your nursing clinical judgement (critical thinking), each unfolding nursing case study includes answers laid out by Blooms Taxonomy to help you see that you are progressing to clinical analysis.We encourage you to read the case study and really through the “critical thinking checks” as this is where the real learning occurs. If you get tripped up by a specific question, no worries, just dig into an associated lesson on the topic and reinforce your understanding. In the end, that is what nursing case studies are all about – growing in your clinical judgement.

Nursing Case Studies Introduction

Cardiac nursing case studies.

- 6 Questions

- 7 Questions

- 5 Questions

- 4 Questions

GI/GU Nursing Case Studies

- 2 Questions

- 8 Questions

Obstetrics Nursing Case Studies

Respiratory nursing case studies.

- 10 Questions

Pediatrics Nursing Case Studies

- 3 Questions

- 12 Questions

Neuro Nursing Case Studies

Mental health nursing case studies.

- 9 Questions

Metabolic/Endocrine Nursing Case Studies

Other nursing case studies.

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Perspective

- Open access

- Published: 16 October 2014

A woman with asthma: a whole systems approach to supporting self-management

- Hilary Pinnock 1 ,

- Elisabeth Ehrlich 1 ,

- Gaylor Hoskins 2 &

- Ron Tomlins 3

npj Primary Care Respiratory Medicine volume 24 , Article number: 14063 ( 2014 ) Cite this article

16k Accesses

2 Citations

6 Altmetric

Metrics details

- Health care

A 35-year-old lady attends for review of her asthma following an acute exacerbation. There is an extensive evidence base for supported self-management for people living with asthma, and international and national guidelines emphasise the importance of providing a written asthma action plan. Effective implementation of this recommendation for the lady in this case study is considered from the perspective of a patient, healthcare professional, and the organisation. The patient emphasises the importance of developing a partnership based on honesty and trust, the need for adherence to monitoring and regular treatment, and involvement of family support. The professional considers the provision of asthma self-management in the context of a structured review, with a focus on a self-management discussion which elicits the patient’s goals and preferences. The organisation has a crucial role in promoting, enabling and providing resources to support professionals to provide self-management. The patient’s asthma control was assessed and management optimised in two structured reviews. Her goal was to avoid disruption to her work and her personalised action plan focused on achieving that goal.

Similar content being viewed by others

Barriers to implementing asthma self-management in Malaysian primary care: qualitative study exploring the perspectives of healthcare professionals

The self-management abilities test (SMAT): a tool to identify the self-management abilities of adults with bronchiectasis

Improving primary care management of asthma: do we know what really works?

A 35-year-old sales representative attends the practice for an asthma review. Her medical record notes that she has had asthma since childhood, and although for many months of the year her asthma is well controlled (when she often reduces or stops her inhaled steroids), she experiences one or two exacerbations a year requiring oral steroids. These are usually triggered by a viral upper respiratory infection, though last summer when the pollen count was particularly high she became tight chested and wheezy for a couple of weeks.

Her regular prescription is for fluticasone 100 mcg twice a day, and salbutamol as required. She has a young family and a busy lifestyle so does not often manage to find time to attend the asthma clinic. A few weeks previously, an asthma attack had interfered with some important work-related travel, and she has attended the clinic on this occasion to ask about how this can be managed better in the future. There is no record of her having been given an asthma action plan.

What do we know about asthma self-management? The academic perspective

Supported self-management reduces asthma morbidity.

The lady in this case study is struggling to maintain control of her asthma within the context of her busy professional and domestic life. The recent unfortunate experience which triggered this consultation offers a rare opportunity to engage with her and discuss how she can manage her asthma better. It behoves the clinician whom she is seeing (regardless of whether this is in a dedicated asthma clinic or an appointment in a routine general practice surgery) to grasp the opportunity and discuss self-management and provide her with a (written) personalised asthma action plan (PAAP).

The healthcare professional advising the lady is likely to be aware that international and national guidelines emphasise the importance of supporting self-management. 1 – 4 There is an extensive evidence base for asthma self-management: a recent synthesis identified 22 systematic reviews summarising data from 260 randomised controlled trials encompassing a broad range of demographic, clinical and healthcare contexts, which concluded that asthma self-management reduces emergency use of healthcare resources, including emergency department visits, hospital admissions and unscheduled consultations and improves markers of asthma control, including reduced symptoms and days off work, and improves quality of life. 1 , 2 , 5 – 12 Health economic analysis suggests that it is not only clinically effective, but also a cost-effective intervention. 13

Personalised asthma action plans

Key features of effective self-management approaches are:

Self-management education should be reinforced by provision of a (written) PAAP which reminds patients of their regular treatment, how to monitor and recognise that control is deteriorating and the action they should take. 14 – 16 As an adult, our patient can choose whether she wishes to monitor her control with symptoms or by recording peak flows (or a combination of both). 6 , 8 , 9 , 14 Symptom-based monitoring is generally better in children. 15 , 16

Plans should have between two and three action points including emergency doses of reliever medication; increasing low dose (or recommencing) inhaled steroids; or starting a course of oral steroids according to severity of the exacerbation. 14

Personalisation of the action plan is crucial. Focussing specifically on what actions she could take to prevent a repetition of the recent attack is likely to engage her interest. Not all patients will wish to start oral steroids without advice from a healthcare professional, though with her busy lifestyle and travel our patient is likely to be keen to have an emergency supply of prednisolone. Mobile technology has the potential to support self-management, 17 , 18 though a recent systematic review concluded that none of the currently available smart phone ‘apps’ were fit for purpose. 19

Identification and avoidance of her triggers is important. As pollen seems to be a trigger, management of allergic rhinitis needs to be discussed (and included in her action plan): she may benefit from regular use of a nasal steroid spray during the season. 20

Self-management as recommended by guidelines, 1 , 2 focuses narrowly on adherence to medication/monitoring and the early recognition/remediation of exacerbations, summarised in (written) PAAPs. Patients, however, may want to discuss how to reduce the impact of asthma on their life more generally, 21 including non-pharmacological approaches.

Supported self-management

The impact is greater if self-management education is delivered within a comprehensive programme of accessible, proactive asthma care, 22 and needs to be supported by ongoing regular review. 6 With her busy lifestyle, our patient may be reluctant to attend follow-up appointments, and once her asthma is controlled it may be possible to make convenient arrangements for professional review perhaps by telephone, 23 , 24 or e-mail. Flexible access to professional advice (e.g., utilising diverse modes of consultation) is an important component of supporting self-management. 25

The challenge of implementation

Implementation of self-management, however, remains poor in routine clinical practice. A recent Asthma UK web-survey estimated that only 24% of people with asthma in the UK currently have a PAAP, 26 with similar figures from Sweden 27 and Australia. 28 The general practitioner may feel that they do not have time to discuss self-management in a routine surgery appointment, or may not have a supply of paper-based PAAPs readily available. 29 However, as our patient rarely finds time to attend the practice, inviting her to make an appointment for a future clinic is likely to be unsuccessful and the opportunity to provide the help she needs will be missed.

The solution will need a whole systems approach

A systematic meta-review of implementing supported self-management in long-term conditions (including asthma) concluded that effective implementation was multifaceted and multidisciplinary; engaging patients, training and motivating professionals within the context of an organisation which actively supported self-management. 5 This whole systems approach considers that although patient education, professional training and organisational support are all essential components of successful support, they are rarely effective in isolation. 30 A systematic review of interventions that promote provision/use of PAAPs highlighted the importance of organisational systems (e.g., sending blank PAAPs with recall reminders). 31 A patient offers her perspective ( Box 1 ), a healthcare professional considers the clinical challenge, and the challenges are discussed from an organisational perspective.

Box 1: What self-management help should this lady expect from her general practitioner or asthma nurse? The patient’s perspective

The first priority is that the patient is reassured that her condition can be managed successfully both in the short and the long term. A good working relationship with the health professional is essential to achieve this outcome. Developing trust between patient and healthcare professional is more likely to lead to the patient following the PAAP on a long-term basis.

A review of all medication and possible alternative treatments should be discussed. The patient needs to understand why any changes are being made and when she can expect to see improvements in her condition. Be honest, as sometimes it will be necessary to adjust dosages before benefits are experienced. Be positive. ‘There are a number of things we can do to try to reduce the impact of asthma on your daily life’. ‘Preventer treatment can protect against the effect of pollen in the hay fever season’. If possible, the same healthcare professional should see the patient at all follow-up appointments as this builds trust and a feeling of working together to achieve the aim of better self-management.

Is the healthcare professional sure that the patient knows how to take her medication and that it is taken at the same time each day? The patient needs to understand the benefit of such a routine. Medication taken regularly at the same time each day is part of any self-management regime. If the patient is unused to taking medication at the same time each day then keeping a record on paper or with an electronic device could help. Possibly the patient could be encouraged to set up a system of reminders by text or smartphone.

Some people find having a peak flow meter useful. Knowing one's usual reading means that any fall can act as an early warning to put the PAAP into action. Patients need to be proactive here and take responsibility.

Ongoing support is essential for this patient to ensure that she takes her medication appropriately. Someone needs to be available to answer questions and provide encouragement. This could be a doctor or a nurse or a pharmacist. Again, this is an example of the partnership needed to achieve good asthma control.

It would also be useful at a future appointment to discuss the patient’s lifestyle and work with her to reduce her stress. Feeling better would allow her to take simple steps such as taking exercise. It would also be helpful if all members of her family understood how to help her. Even young children can do this.

From personal experience some people know how beneficial it is to feel they are in a partnership with their local practice and pharmacy. Being proactive produces dividends in asthma control.

What are the clinical challenges for the healthcare professional in providing self-management support?

Due to the variable nature of asthma, a long-standing history may mean that the frequency and severity of symptoms, as well as what triggers them, may have changed over time. 32 Exacerbations requiring oral steroids, interrupting periods of ‘stability’, indicate the need for re-assessment of the patient’s clinical as well as educational needs. The patient’s perception of stability may be at odds with the clinical definition 1 , 33 —a check on the number of short-acting bronchodilator inhalers the patient has used over a specific period of time is a good indication of control. 34 Assessment of asthma control should be carried out using objective tools such as the Asthma Control Test or the Royal College of Physicians three questions. 35 , 36 However, it is important to remember that these assessment tools are not an end in themselves but should be a springboard for further discussion on the nature and pattern of symptoms. Balancing work with family can often make it difficult to find the time to attend a review of asthma particularly when the patient feels well. The practice should consider utilising other means of communication to maintain contact with patients, encouraging them to come in when a problem is highlighted. 37 , 38 Asthma guidelines advocate a structured approach to ensure the patient is reviewed regularly and recommend a detailed assessment to enable development of an appropriate patient-centred (self)management strategy. 1 – 4

Although self-management plans have been shown to be successful for reducing the impact of asthma, 21 , 39 the complexity of managing such a fluctuating disease on a day-to-day basis is challenging. During an asthma review, there is an opportunity to work with the patient to try to identify what triggers their symptoms and any actions that may help improve or maintain control. 38 An integral part of personalised self-management education is the written PAAP, which gives the patient the knowledge to respond to the changes in symptoms and ensures they maintain control of their asthma within predetermined parameters. 9 , 40 The PAAP should include details on how to monitor asthma, recognise symptoms, how to alter medication and what to do if the symptoms do not improve. The plan should include details on the treatment to be taken when asthma is well controlled, and how to adjust it when the symptoms are mild, moderate or severe. These action plans need to be developed between the doctor, nurse or asthma educator and the patient during the review and should be frequently reviewed and updated in partnership (see Box 1). Patient preference as well as clinical features such as whether she under- or over-perceives her symptoms should be taken into account when deciding whether the action plan is peak flow or symptom-driven. Our patient has a lot to gain from having an action plan. She has poorly controlled asthma and her lifestyle means that she will probably see different doctors (depending who is available) when she needs help. Being empowered to self-manage could make a big difference to her asthma control and the impact it has on her life.

The practice should have protocols in place, underpinned by specific training to support asthma self-management. As well as ensuring that healthcare professionals have appropriate skills, this should include training for reception staff so that they know what action to take if a patient telephones to say they are having an asthma attack.

However, focusing solely on symptom management strategies (actions) to follow in the presence of deteriorating symptoms fails to incorporate the patients’ wider views of asthma, its management within the context of her/his life, and their personal asthma management strategies. 41 This may result in a failure to use plans to maximise their health potential. 21 , 42 A self-management strategy leading to improved outcomes requires a high level of patient self-efficacy, 43 a meaningful partnership between the patient and the supporting health professional, 42 , 44 and a focused self-management discussion. 14

Central to both the effectiveness and personalisation of action plans, 43 , 45 in particular the likelihood that the plan will lead to changes in patients’ day-to-day self-management behaviours, 45 is the identification of goals. Goals are more likely to be achieved when they are specific, important to patients, collaboratively set and there is a belief that these can be achieved. Success depends on motivation 44 , 46 to engage in a specific behaviour to achieve a valued outcome (goal) and the ability to translate the behavioural intention into action. 47 Action and coping planning increases the likelihood that patient behaviour will actually change. 44 , 46 , 47 Our patient has a goal: she wants to avoid having her work disrupted by her asthma. Her personalised action plan needs to explicitly focus on achieving that goal.

As providers of self-management support, health professionals must work with patients to identify goals (valued outcomes) that are important to patients, that may be achievable and with which they can engage. The identification of specific, personalised goals and associated feasible behaviours is a prerequisite for the creation of asthma self-management plans. Divergent perceptions of asthma and how to manage it, and a mismatch between what patients want/need from these plans and what is provided by professionals are barriers to success. 41 , 42

What are the challenges for the healthcare organisation in providing self-management support?

A number of studies have demonstrated the challenges for primary care physicians in providing ongoing support for people with asthma. 31 , 48 , 49 In some countries, nurses and other allied health professionals have been trained as asthma educators and monitor people with stable asthma. These resources are not always available. In addition, some primary care services are delivered in constrained systems where only a few minutes are available to the practitioner in a consultation, or where only a limited range of asthma medicines are available or affordable. 50

There is recognition that the delivery of quality care depends on the competence of the doctor (and supporting health professionals), the relationship between the care providers and care recipients, and the quality of the environment in which care is delivered. 51 This includes societal expectations, health literacy and financial drivers.

In 2001, the Australian Government adopted a programme developed by the General Practitioner Asthma Group of the National Asthma Council Australia that provided a structured approach to the implementation of asthma management guidelines in a primary care setting. 52 Patients with moderate-to-severe asthma were eligible to participate. The 3+ visit plan required confirmation of asthma diagnosis, spirometry if appropriate, assessment of trigger factors, consideration of medication and patient self-management education including provision of a written PAAP. These elements, including regular medical review, were delivered over three visits. Evaluation demonstrated that the programme was beneficial but that it was difficult to complete the third visit in the programme. 53 – 55 Accordingly, the programme, renamed the Asthma Cycle of Care, was modified to incorporate two visits. 56 Financial incentives are provided to practices for each patient who receives this service each year.

Concurrently, other programmes were implemented which support practice-based care. Since 2002, the National Asthma Council has provided best-practice asthma and respiratory management education to health professionals, 57 and this programme will be continuing to 2017. The general practitioner and allied health professional trainers travel the country to provide asthma and COPD updates to groups of doctors, nurses and community pharmacists. A number of online modules are also provided. The PACE (Physician Asthma Care Education) programme developed by Noreen Clark has also been adapted to the Australian healthcare system. 58 In addition, a pharmacy-based intervention has been trialled and implemented. 59

To support these programmes, the National Asthma Council ( www.nationalasthma.org.au ) has developed resources for use in practices. A strong emphasis has been on the availability of a range of PAAPs (including plans for using adjustable maintenance dosing with ICS/LABA combination inhalers), plans for indigenous Australians, paediatric plans and plans translated into nine languages. PAAPs embedded in practice computer systems are readily available in consultations, and there are easily accessible online paediatric PAAPs ( http://digitalmedia.sahealth.sa.gov.au/public/asthma/ ). A software package, developed in the UK, can be downloaded and used to generate a pictorial PAAP within the consultation. 60

One of the strongest drivers towards the provision of written asthma action plans in Australia has been the Asthma Friendly Schools programme. 61 , 62 Established with Australian Government funding and the co-operation of Education Departments of each state, the Asthma Friendly Schools programme engages schools to address and satisfy a set of criteria that establishes an asthma-friendly environment. As part of accreditation, the school requires that each child with asthma should have a written PAAP prepared by their doctor to assist (trained) staff in managing a child with asthma at school.

The case study continues...

The initial presentation some weeks ago was during an exacerbation of asthma, which may not be the best time to educate a patient. It is, however, a splendid time to build on their motivation to feel better. She agreed to return after her asthma had settled to look more closely at her asthma control, and an appointment was made for a routine review.

At this follow-up consultation, the patient’s diagnosis was reviewed and confirmed and her trigger factors discussed. For this lady, respiratory tract infections are the usual trigger but allergic factors during times of high pollen count may also be relevant. Assessment of her nasal airway suggested that she would benefit from better control of allergic rhinitis. Other factors were discussed, as many patients are unaware that changes in air temperature, exercise and pets can also trigger asthma exacerbations. In addition, use of the Asthma Control Test was useful as an objective assessment of control as well as helping her realise what her life could be like! Many people with long-term asthma live their life within the constraints of their illness, accepting that is all that they can do.

After assessing the level of asthma control, a discussion about management options—trigger avoidance, exercise and medicines—led to the development of a written PAAP. Asthma can affect the whole family, and ways were explored that could help her family understand why it is important that she finds time in the busy domestic schedules to take her regular medication. Family and friends can also help by understanding what triggers her asthma so that they can avoid exposing her to perfumes, pollens or pets that risk triggering her symptoms. Information from the national patient organisation was provided to reinforce the messages.

The patient agreed to return in a couple of weeks, and a recall reminder was set up. At the second consultation, the level of control since the last visit will be explored including repeat spirometry, if appropriate. Further education about the pathophysiology of asthma and how to recognise early warning signs of loss of control can be given. Device use will be reassessed and the PAAP reviewed. Our patient’s goal is to avoid disruption to her work and her PAAP will focus on achieving that goal. Finally, agreement will be reached with the patient about future routine reviews, which, now that she has a written PAAP, could be scheduled by telephone if all is well, or face-to-face if a change in her clinical condition necessitates a more comprehensive review.

Global Initiative for Asthma. Global Strategy for Asthma Management and Prevention, 2012. Available from: http://www.ginasthma.org (accessed July 2013).

British Thoracic Society/Scottish Intercollegiate Guideline Network British Guideline on the Management of Asthma. Thorax 2008; 63 (Suppl 4 iv1–121, updated version available from: http://www.sign.ac.uk (accessed January 2014).

Article Google Scholar

National Asthma Council Australia. Australian Asthma Handbook. Available from: http://www.nationalasthma.org.au/handbook (accessed May 2014).

National Asthma Education and Prevention Program (NAEPP) Coordinating Committee. Expert Panel Report 3 (EPR3): Guidelines for the Diagnosis and Management of Asthma. Available from: https://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/guidelines/asthma/asthgdln.htm (accessed May 2014).

Taylor SJC, Pinnock H, Epiphaniou E, Pearce G, Parke H . A rapid synthesis of the evidence on interventions supporting self-management for people with long-term conditions. (PRISMS Practical Systematic Review of Self-Management Support for long-term conditions). Health Serv Deliv Res (in press).

Gibson PG, Powell H, Wilson A, Abramson MJ, Haywood P, Bauman A et al. Self-management education and regular practitioner review for adults with asthma. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2002: (Issue 3) Art No. CD001117.

Tapp S, Lasserson TJ, Rowe BH . Education interventions for adults who attend the emergency room for acute asthma. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2007: (Issue 3) Art No. CD003000.

Powell H, Gibson PG . Options for self-management education for adults with asthma. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2002: (Issue 3) Art No: CD004107.

Toelle B, Ram FSF . Written individualised management plans for asthma in children and adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2004: (Issue 1) Art No. CD002171.

Lefevre F, Piper M, Weiss K, Mark D, Clark N, Aronson N . Do written action plans improve patient outcomes in asthma? An evidence-based analysis. J Fam Pract 2002; 51 : 842–848.

PubMed Google Scholar

Boyd M, Lasserson TJ, McKean MC, Gibson PG, Ducharme FM, Haby M . Interventions for educating children who are at risk of asthma-related emergency department attendance. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2009: (Issue 2) Art No.CD001290.

Bravata DM, Gienger AL, Holty JE, Sundaram V, Khazeni N, Wise PH et al. Quality improvement strategies for children with asthma: a systematic review. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med 2009; 163 : 572–581.

Bower P, Murray E, Kennedy A, Newman S, Richardson G, Rogers A . Self-management support interventions to reduce health care utilisation without compromising outcomes: a rapid synthesis of the evidence. Available from: http://www.nets.nihr.ac.uk/projects/hsdr/11101406 (accessed April 2014).

Gibson PG, Powell H . Written action plans for asthma: an evidence-based review of the key components. Thorax 2004; 59 : 94–99.

Article CAS Google Scholar

Bhogal SK, Zemek RL, Ducharme F . Written action plans for asthma in children. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2006: (Issue 3) Art No. CD005306.

Zemek RL, Bhogal SK, Ducharme FM . Systematic review of randomized controlled trials examining written action plans in children: what is the plan?. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med 2008; 162 : 157–163.

Pinnock H, Slack R, Pagliari C, Price D, Sheikh A . Understanding the potential role of mobile phone based monitoring on asthma self-management: qualitative study. Clin Exp Allergy 2007; 37 : 794–802.

de Jongh T, Gurol-Urganci I, Vodopivec-Jamsek V, Car J, Atun R . Mobile phone messaging for facilitating self-management of long-term illnesses. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2012: (Issue 12) Art No. CD007459.

Huckvale K, Car M, Morrison C, Car J . Apps for asthma self-management: a systematic assessment of content and tools. BMC Med 2012; 10 : 144.

Allergic Rhinitis and its Impact on Asthma. Management of Allergic Rhinitis and its Impact on Asthma: Pocket Guide. ARIA 2008. Available from: http://www.whiar.org (accessed May 2014).

Ring N, Jepson R, Hoskins G, Wilson C, Pinnock H, Sheikh A et al. Understanding what helps or hinders asthma action plan use: a systematic review and synthesis of the qualitative literature. Patient Educ Couns 2011; 85 : e131–e143.

Moullec G, Gour-Provencal G, Bacon SL, Campbell TS, Lavoie KL . Efficacy of interventions to improve adherence to inhaled corticosteroids in adult asthmatics: Impact of using components of the chronic care model. Respir Med 2012; 106 : 1211–1225.

Pinnock H, Bawden R, Proctor S, Wolfe S, Scullion J, Price D et al. Accessibility, acceptability and effectiveness of telephone reviews for asthma in primary care: randomised controlled trial. BMJ 2003; 326 : 477–479.

Pinnock H, Adlem L, Gaskin S, Harris J, Snellgrove C, Sheikh A . Accessibility, clinical effectiveness and practice costs of providing a telephone option for routine asthma reviews: phase IV controlled implementation study. Br J Gen Pract 2007; 57 : 714–722.

PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Kielmann T, Huby G, Powell A, Sheikh A, Price D, Williams S et al. From support to boundary: a qualitative study of the border between self care and professional care. Patient Educ Couns 2010; 79 : 55–61.

Asthma UK . Compare your care report. Asthma UK, 2013. Available from: http://www.asthma.org.uk (accessed January 2014).

Stallberg B, Lisspers K, Hasselgren M, Janson C, Johansson G, Svardsudd K . Asthma control in primary care in Sweden: a comparison between 2001 and 2005. Prim Care Respir J 2009; 18 : 279–286.

Reddel H, Peters M, Everett P, Flood P, Sawyer S . Ownership of written asthma action plans in a large Australian survey. Eur Respir J 2013; 42 . Abstract 2011.

Wiener-Ogilvie S, Pinnock H, Huby G, Sheikh A, Partridge MR, Gillies J . Do practices comply with key recommendations of the British Asthma Guideline? If not, why not? Prim Care Respir J 2007; 16 : 369–377.

Kennedy A, Rogers A, Bower P . Support for self care for patients with chronic disease. BMJ 2007; 335 : 968–970.

Ring N, Malcolm C, Wyke S, Macgillivray S, Dixon D, Hoskins G et al. Promoting the Use of Personal Asthma Action Plans: A Systematic Review. Prim Care Respir J 2007; 16 : 271–283.

Taylor DR, Bateman ED, Boulet LP, Boushey HA, Busse WW, Casale TB et al. A new perspective on concepts of asthma severity and control. Eur Respir J 2008; 32 : 545–554.

Horne R . Compliance, adherence, and concordance: implications for asthma treatment. Chest 2006; 130 (suppl): 65S–72S.

Reddel HK, Taylor DR, Bateman ED, Boulet L-P, Boushey HA, Busse WW et al. An official American Thoracic Society/European Respiratory Society statement: asthma control and exacerbations standardizing endpoints for clinical asthma trials and clinical practice. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2009; 180 : 59–99.

Thomas M, Kay S, Pike J, Rosenzweig JR, Hillyer EV, Price D . The Asthma Control Test (ACT) as a predictor of GINA guideline-defined asthma control: analysis of a multinational cross-sectional survey. Prim Care Respir J 2009; 18 : 41–49.

Hoskins G, Williams B, Jackson C, Norman P, Donnan P . Assessing asthma control in UK primary care: use of routinely collected prospective observational consultation data to determine appropriateness of a variety of control assessment models. BMC Fam Pract 2011; 12 : 105.

Pinnock H, Fletcher M, Holmes S, Keeley D, Leyshon J, Price D et al. Setting the standard for routine asthma consultations: a discussion of the aims, process and outcomes of reviewing people with asthma in primary care. Prim Care Respir J 2010; 19 : 75–83.

McKinstry B, Hammersley V, Burton C, Pinnock H, Elton RA, Dowell J et al. The quality, safety and content of telephone and face-to-face consultations: a comparative study. Qual Saf Health Care 2010; 19 : 298–303.

Gordon C, Galloway T . Review of Findings on Chronic Disease Self-Management Program (CDSMP) Outcomes: Physical, Emotional & Health-Related Quality of Life, Healthcare Utilization and Costs . Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and National Council on Aging: Atlanta, GA, USA, 2008.

Beasley R, Crane J . Reducing asthma mortality with the self-management plan system of care. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2001; 163 : 3–4.

Ring N, Jepson R, Pinnock H, Wilson C, Hoskins G, Sheikh A et al. Encouraging the promotion and use of asthma action plans: a cross study synthesis of qualitative and quantitative evidence. Trials 2012; 13 : 21.

Jones A, Pill R, Adams S . Qualitative study of views of health professionals and patients on guided self-management plans for asthma. BMJ 2000; 321 : 1507–1510.

Bandura A . Self-efficacy: toward a unifying theory of behavioural change. Psychol Rev 1977; 84 : 191–215.

Gollwitzer PM, Sheeran P . Implementation intentions and goal achievement: a meta-analysis of effects and processes. Adv Exp Soc Psychol 2006; 38 : 69–119.

Google Scholar

Hardeman W, Johnston M, Johnston DW, Bonetti D, Wareham NJ, Kinmonth AL . Application of the theory of planned behaviour change interventions: a systematic review. Psychol Health 2002; 17 : 123–158.

Schwarzer R . Modeling health behavior change: how to predict and modify the adoption and maintenance of health behaviors. Appl Psychol 2008; 57 : 1–29.

Sniehotta F . Towards a theory of intentional behaviour change: plans, planning, and self-regulation. Br J Health Psychol 2009; 14 : 261–273.

Okelo SO, Butz AM, Sharma R, Diette GB, Pitts SI, King TM et al. Interventions to modify health care provider adherence to asthma guidelines: a systematic review. Pediatrics 2013; 132 : 517–534.

Grol R, Grimshaw RJ . From best evidence to best practice: effective implementation of change in patients care. Lancet 2003; 362 : 1225–1230.

Jusef L, Hsieh C-T, Abad L, Chaiyote W, Chin WS, Choi Y-J et al. Primary care challenges in treating paediatric asthma in the Asia-Pacific region. Prim Care Respir J 2013; 22 : 360–362.

Donabedian A . Evaluating the quality of medical care. Milbank Q 2005; 83 : 691–729.

Fardy HJ . Moving towards organized care of chronic disease. The 3+ visit plan. Aust Fam Physician 2001; 30 : 121–125.

CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Glasgow NJ, Ponsonby AL, Yates R, Beilby J, Dugdale P . Proactive asthma care in childhood: general practice based randomised controlled trial. BMJ 2003; 327 : 659.

Douglass JA, Goemann DP, Abramson MJ . Asthma 3+ visit plan: a qualitative evaluation. Intern Med J 2005; 35 : 457–462.

Beilby J, Holton C . Chronic disease management in Australia; evidence and policy mismatch, with asthma as an example. Chronic Illn 2005; 1 : 73–80.

The Department of Health. Asthma Cycle of Care. Accessed on 14 May 2014 at http://www.health.gov.au/internet/main/publishing.nsf/Content/asthma-cycle .

National Asthma Council Australia. Asthma and Respiratory Education Program. Accessed on 14 May 2014 at http://www.nationalasthma.org.au/health-professionals/education-training/asthma-respiratory-education-program .

Patel MR, Shah S, Cabana MD, Sawyer SM, Toelle B, Mellis C et al. Translation of an evidence-based asthma intervention: Physician Asthma Care Education (PACE) in the United States and Australia. Prim Care Respir J 2013; 22 : 29–34.

Armour C, Bosnic-Anticevich S, Brilliant M, Burton D, Emmerton L, Krass I et al. Pharmacy Asthma Care Program (PACP) improves outcomes for patients in the community. Thorax 2007; 62 : 496–502.

Roberts NJ, Mohamed Z, Wong PS, Johnson M, Loh LC, Partridge MR . The development and comprehensibility of a pictorial asthma action plan. Patient Educ Couns 2009; 74 : 12–18.

Henry RL, Gibson PG, Vimpani GV, Francis JL, Hazell J . Randomised controlled trial of a teacher-led asthma education program. Pediatr Pulmonol 2004; 38 : 434–442.

National Asthma Council Australia. Asthma Friendly Schools program. Accessed on 14 May 2014 at http://www.asthmaaustralia.org.au/Asthma-Friendly-Schools.aspx .

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Asthma UK Centre for Applied Research, Centre for Population Health Sciences, The University of Edinburgh, Edinburgh, UK,

Hilary Pinnock & Elisabeth Ehrlich

NMAHP-RU, University of Stirling, Stirling, UK,

Gaylor Hoskins

Discipline of General Practice, University of Sydney, Sydney, NSW, Australia

Ron Tomlins

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Hilary Pinnock .

Ethics declarations

Competing interests.

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Rights and permissions

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in the credit line; if the material is not included under the Creative Commons license, users will need to obtain permission from the license holder to reproduce the material. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Pinnock, H., Ehrlich, E., Hoskins, G. et al. A woman with asthma: a whole systems approach to supporting self-management. npj Prim Care Resp Med 24 , 14063 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1038/npjpcrm.2014.63

Download citation

Received : 23 June 2014

Revised : 15 July 2014

Accepted : 15 July 2014

Published : 16 October 2014

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1038/npjpcrm.2014.63

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

Quick links

- Explore articles by subject

- Guide to authors

- Editorial policies

Sign up for the Nature Briefing newsletter — what matters in science, free to your inbox daily.

- Case report

- Open access

- Published: 21 February 2018

Pediatric severe asthma: a case series report and perspectives on anti-IgE treatment

- Virginia Mirra 1 ,

- Silvia Montella 1 &

- Francesca Santamaria 1

BMC Pediatrics volume 18 , Article number: 73 ( 2018 ) Cite this article

11k Accesses

14 Citations

12 Altmetric

Metrics details

The primary goal of asthma management is to achieve disease control for reducing the risk of future exacerbations and progressive loss of lung function. Asthma not responding to treatment may result in significant morbidity. In many children with uncontrolled symptoms, the diagnosis of asthma may be wrong or adherence to treatment may be poor. It is then crucial to distinguish these cases from the truly “severe therapy-resistant” asthmatics by a proper filtering process. Herein we report on four cases diagnosed as difficult asthma, detail the workup that resulted in the ultimate diagnosis, and provide the process that led to the prescription of omalizumab.

Case presentation

All children had been initially referred because of asthma not responding to long-term treatment with high-dose inhaled steroids, long-acting β 2 -agonists and leukotriene receptor antagonists. Definitive diagnosis was severe asthma. Three out four patients were treated with omalizumab, which improved asthma control and patients’ quality of life. We reviewed the current literature on the diagnostic approach to the disease and on the comorbidities associated with difficult asthma and presented the perspectives on omalizumab treatment in children and adolescents. Based on the evidence from the literature review, we also proposed an algorithm for the diagnosis of pediatric difficult-to-treat and severe asthma.

Conclusions

The management of asthma is becoming much more patient-specific, as more and more is learned about the biology behind the development and progression of asthma. The addition of omalizumab, the first targeted biological treatment approved for asthma, has led to renewed optimism in the management of children and adolescents with atopic severe asthma.

Peer Review reports

Children with poor asthma control have an increased risk of severe exacerbations and progressive loss of lung function, which results in the relevant use of health resources and impaired quality of life (QoL) [ 1 ]. Therefore, the primary goal of asthma management at all ages is to achieve disease control [ 2 , 3 , 4 ].

According to recent international guidelines, patients with uncontrolled asthma require a prolonged maintenance treatment with high-dose inhaled corticosteroids (ICS) in association with a long-acting β 2 -agonist (LABA) plus oral leukotriene receptor antagonist (LTRA) (Table 1 ) [ 5 ].

Nevertheless, in the presence of persistent lack of control, reversible factors such as adherence to treatment or inhalation technique should be first checked for, and diseases that can masquerade as asthma should be promptly excluded. Finally, additional strategies, in particular anti-immunoglobulin E (anti-IgE) treatment (omalizumab), are suggested for patients with moderate or severe allergic asthma that remains uncontrolled in Step 4 [ 5 ].

Herein, we reviewed the demographics, clinical presentation and treatment of four patients with uncontrolled severe asthma from our institution in order to explain why we decided to prescribe omalizumab. We also provided a review of the current literature that focuses on recent advances in the diagnosis of pediatric difficult asthma and the associated comorbidities, and summarizes the perspectives on anti-IgE treatment in children and adolescents.

Case presentations

Table 2 summarizes the clinical characteristics and the triggers/comorbidities of the cases at referral to our Institution. Unfortunately, data on psychological factors, sleep apnea, and hyperventilation syndrome were not available in any case. Clinical, lung function and airway inflammation findings at baseline and after 12 months of follow-up are reported in Table 3 . In the description of our cases, we used the terminology recommended by the ERS/ATS guidelines on severe asthma [ 6 ].

A full-term male had severe preschool wheezing and, since age 3, recurrent, severe asthma exacerbations with frequent hospital admissions. At age 11, severe asthma was diagnosed. Sensitization to multiple inhalant allergens (i.e., house dust mites, dog dander, Graminaceae pollen mix, and Parietaria judaica ) and high serum IgE levels (1548 KU/l) were found. Body mass index (BMI) was within normal range. Combined treatment with increasing doses of ICS (fluticasone, up to 1000 μg/day) in association with LABA (salmeterol, 100 μg/day) plus LTRA (montelukast, 5 mg/day) has been administered over 2 years. Nevertheless, persistent symptoms and monthly hospital admissions due to asthma exacerbations despite correct inhaler technique and good adherence were reported. Parents refused to perform any test to exclude gastroesophageal reflux (GER) as comorbidity [ 6 ]. However, an ex-juvantibus 2-month-course with omeprazole was added to asthma treatment [ 7 ], but poor control persisted. Anterior rhinoscopy revealed rhinosinusitis that was treated with nasal steroids for six months [ 8 ], but asthma symptoms were unmodified. Treatment with omalizumab was added at age 12. Reduced hospital admissions for asthma exacerbations, no further need for systemic steroids, and improved QoL score (from 2.0 up to 6.7 out of a maximum of 7 points) were documented over the following months. Unfortunately, after one year of treatment, adherence to omalizumab decreased because of family complaints, and eventually parents withdrew their informed consent and discontinued omalizumab. Currently, by age 17, treatment includes inhaled salmeterol/fluticasone (100 μg/500 μg∙day -1 , respectively) plus oral montelukast (10 mg/day). Satisfactory symptom control is reported, with no asthma exacerbations.